While it is impossible to name all historical and mythological personalities whose signature image became one on a rearing horse, let us try and name the most significant ones. This “genealogy” is somewhat arbitrary, yet, hopefully, it will highlight the most important elements.

King Ashurbanipal killing a lion, 645-35 BC, Neo-Assyrian (Iraq)

Alexander sarcophagus, long side showing a lion hunt, with (l-r) Hephaestion, Abdalonymos and Alexander the Great, circa 320 BC, Ionian or Rhodian workmanchip, Hellenistic

The first two horsemen in the genealogy are both known for their conquests and for the empires they have built. They are

Ashurbanipal (686-628 BC, Assyria/Iraq) and

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC, Macedon/Greece). On both illustrations – relief in Ashurbanipal’s palace and Alexander the Great’s sarcophagus – we see them hunting the lions. This representation was used to convey two messages. Firstly, it was showing their physical prowess and bravery, which was very fitting for the warriors. Secondly, as the lions were viewed as the dangerous predators who can kill people, hunting for them was meant to show care for the people these sovereigns were governing. Hunting was a relatively rare subject in Greek art, and Alexander the Great was paying a lot of attention to how would be depicted (

Lysippos was his personal sculptor, he was the only artist whom the conqueror saw fit to represent him). So why did he choose the lion hunt? According to “History Today”,

in the Middle East the royal lion hunt descended from one ancient empire to the next as an unbroken cultural heritage. As the new king of Asia, Alexander seems to have made a conscious decision to associate himself with this tradition.

Mosaic depicting Bellerophon on rearing Pegasus trampling Chimaera, 2nd half of 2nd century BC, Autun, France (Roman culture)

Hematite magic gem of Solomon, 3rd century, late Roman

Stamp-seal showing a rider with a halo who attacks hydra, possibly with a lance, 5th century or later, Sasanian

Magical pendant with Holy Rider on horseback, trampling over a dragon lying on the ground, 5th century, Byzantine

Amulet with Holy Rider (St. Sisinios) and Virgin Enthroned, 5th-7th century, Byzantine

Next, we have a mythologal hero

Bellerophon and the Holy Rider, often associated with semi-mythological

King Solomon or, sometimes, with Saint Sisinios. Both of them are frequently depicted on a rearing horse (winged

Pegasus for Bellerophon, unnamed horse for the Holy Rider) spearing a personified female monster or demon (

chimera for Bellerophon,

Lilith or hydra for the Holy Rider). While Lilith is human-like she-devil, chimera is

a fire-breathing female monster resembling a lion in the forepart, a goat in the middle, and a dragon behind.

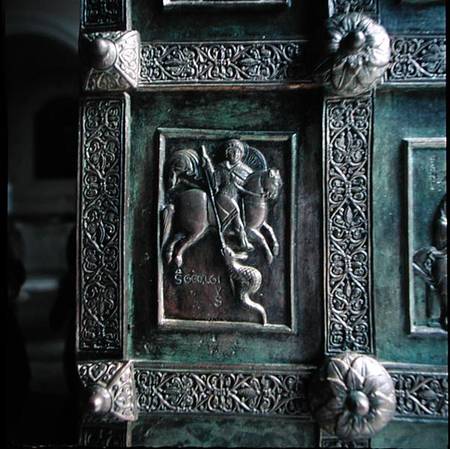

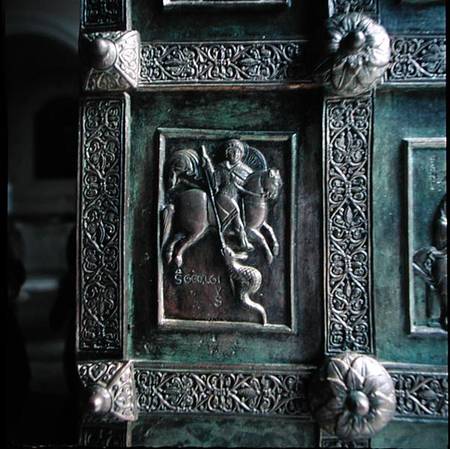

Later, we see the emergence of arguably the most well-known horseman on the rearing horse, Saint George. He was spearing emperor Diocletian in early Eastern tradition, but otherwise, he is spearing the dragon as in the legend of Saint George and the Dragon. The dragon was transferred to Saint George from Saint Theodore of Amasea in the 11th century, and the princess that is saved by Saint George has appeared at around that time. One could suspect the link between Saint George and Bellerophon, and indeed the link exists, as per this The J. Paul Getty’s museum research and this St. Mary Magdalen School of Theology research.

Bronze medallion with Saint George, 9th–12th century, Byzantine

Saint George slaying Diocletian and Saint Theodore slaying a serpent, bas-relief from a 9th-10th-century Georgian monastery

St. George killing the dragon, detail of the main doors, 1179, Cathedral of San Pantaleone, Ravello

St. George fighting with the Dragon, cr. 1505, Raphael, Italy

Relief showing Military Saints Theodore and George, the exterior decor of a church, 13th century, Amaseia, modern Turkey

Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki spearing king Kaloyan of Bulgaria, 1500-50, Russia

The Apostle Santiago on horseback, or Santiago Matamoros, 1649, Francisco Camilo, Spain

Saint Mercurius spearing emperor Julian the Apostate, cr. 1778, painted by Yuhanna al-Armani, Ottoman Egypt

The tradition of a saint on a rearing horse was continued by several other saints:

Saint Mercurius spearing emperor

Julian the Apostate,

Saint James the Moor-slayer slaying the Moors with his sword,

Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki spearing king

Kaloyan of Bulgaria and Saint

Theodore of Amasea spearing the original dragon.

In the 16th century, we see the beginning of another tradition, where the horseman on a rearing horse is no longer killing any enemy, but is shown at the moment of triumph. This tradition has started with Marcus Curtius, a Roman hero whose depiction was on almost any possible object back in the 16th century. It was followed by many European sovereigns, in paintings and in sculpture; then it expanded on other continents.

Equestrian Portrait of Charles V at the battle of Mühlberg, 1548, Titian, Augsburg, Germany

Marcus Curtius, The Roman Heroes series, 1586-1617, circle of Hendrick Goltzius

Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu in front of La Rochelle, 17th century, Unknown

Portrait of King Louis XIV during the War of Devolution, 1668, Charles Le Brun

Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Jacques-Louis David

Golden Horseman, 1735, Dresden, Saxony (Germany)

Augustus III porcelain figurine, Model by Johann J. Kaendler

Bronze Horseman, 1782, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

Statue of Andrew Jackson, 1852, Clark Mills, Washington D.C., U.S.A.

Monument to José de San Martín, completed in 1860, dedicated in 1863, Louis Joseph Daumas, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Statue of Rani of Jhansi, 2010, Fakir Chandra Parida, Shimla, India

There are two particularly interesting sub-types of triumphant representation, the one that became the status symbol in the 17th-18th centuries, and the one where the rider receives the emblems of victory; more on both sub-types just below!

Leave a Reply