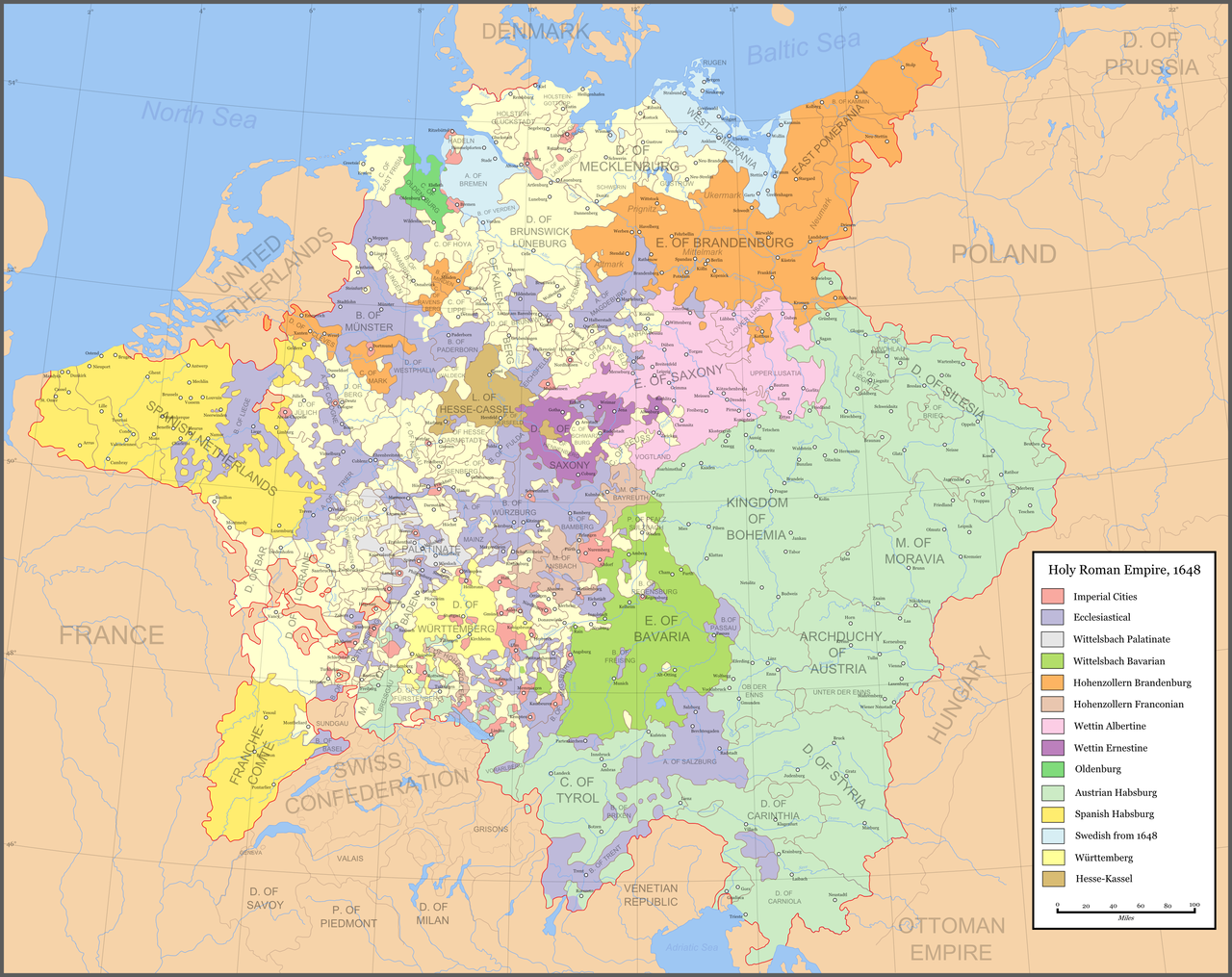

By the end of

European wars of religion, concluded in 1648 with the

Peace of Westphalia, European states have developed a much stronger sense of national identity. At the same time, the Persian empire has shrunk to the size comparable with the modern borders of Iran. Thus, we need to look at horsemen created at that time on a state-by-state basis.

Islamic And Indian Horsemen, 12th – 19th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

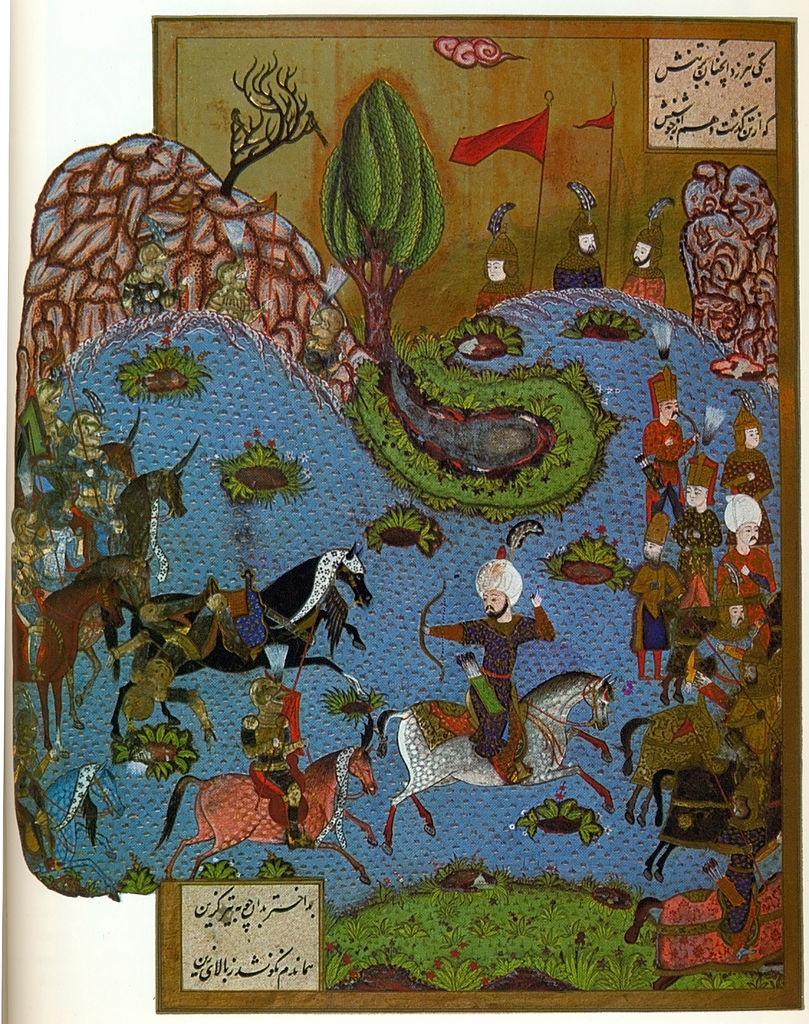

Persian Manuscript Illustrations, 14th – 18th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

While the printing was becoming widespread in Europe, in Persia (present-time Iran) the books and their illustrations were still made by hand. Their iconography, however, is very comparable to some paintings that will be created in Europe in the 16th century.

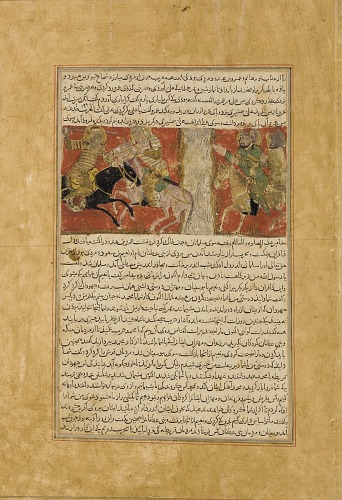

A Persian miniature is a small Persian painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a muraqqa. Persian manuscripts were illustrated from the 3rd century AD, but the greatest period of the Persian miniature began when Persia was ruled by Mongols. The Mongol invasion of 1219 onwards has resulted in Persia becoming a branch of the Mongol Empire. The new court had a galvanising effect on book painting, importing many Chinese works and probably artists, with their long-established tradition of narrative painting.

COMPARANDUM: Grave stelae with a hunting scene, Han dynasty, cr. 206 BC-220 AD, China

COMPARANDUM: Landscape scene from a bronze fitting of a chariot canopy, cr. 2nd – 1st century BC, Dingxian, Hebei province, China

COMPARANDUM: Polo player, detail of a mural from the tomb of Li Xian (the crown prince Zhanghuai), 706, near Xianyang, Shaanxi province, China

COMPARANDUM: Emperor Minghuang’s Journey to Shu, early 8th century, Tang Empire (modern China)

Ismail declares himself shah by entering Tabriz, 2005 or earlier, Chingiz Mehbaliyev, Azerbaijan

The beginning of the 16th century in Persia was marked by the installation of

Safavid dynasty (1501–1736), the end of Mongolian oppression and the return of the national sense of pride. This included

Shahnameh, ‘The Book of Kings’, a long epic poem composed by

Ferdowsi between cr. 977 and 1010. It tells mainly the mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Arab conquest of Iran in the 7th century. This work is of central importance in Persian culture and Persian language, regarded as a literary masterpiece, and definitive of the ethnonational cultural identity of Iran.

Persian art under Islam had never completely forbidden the human figure, and in the miniature tradition the depiction of figures, often in large numbers, is central. This was partly because the miniature is a private form, kept in a book or album and only shown to those the owner chooses. Animals, especially the horses that very often appear, are mostly shown sideways on; even the love-stories that constitute much of the classic material illustrated are conducted largely in the saddle, as far as the prince-protagonist is concerned. Naturally, many of the depictions of the horsemen on rearing horses produced within the Persian culture at that time were the illustrations of Shahnameh.

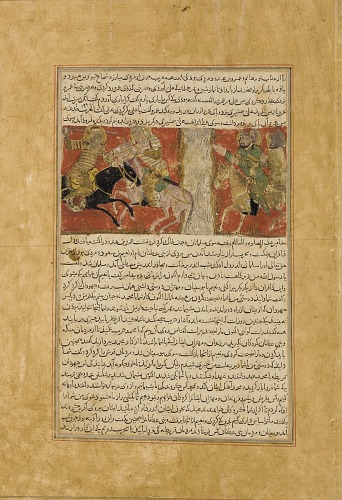

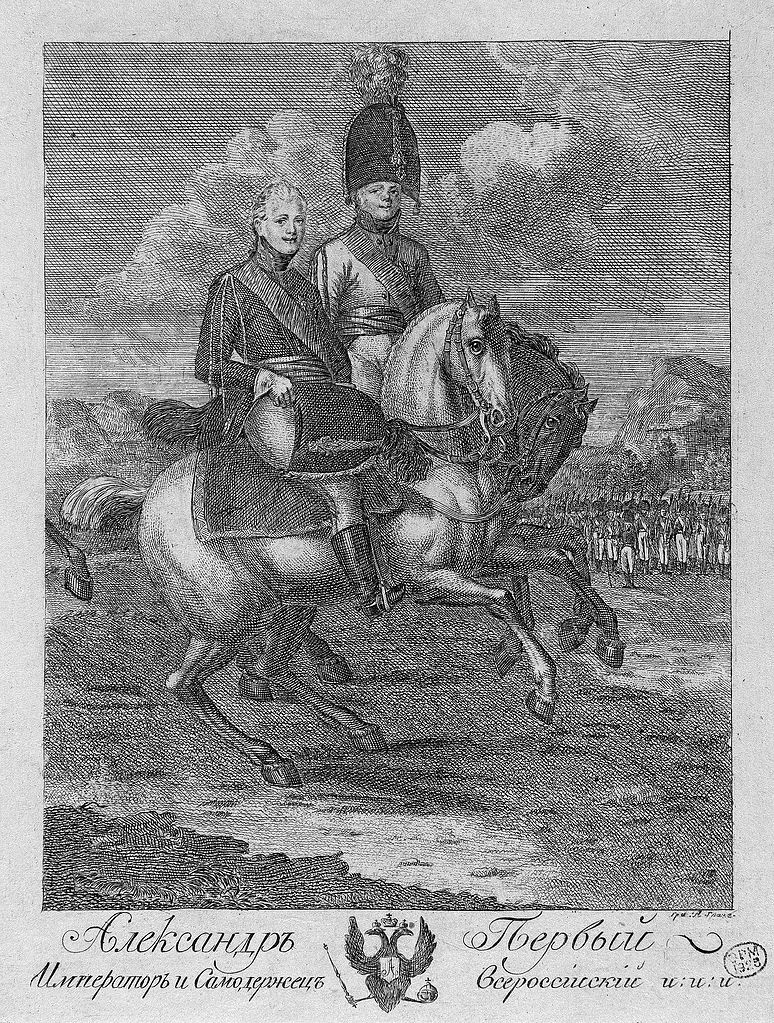

Tarikhnama (Book of history) by Bal'ami, early 14th century, probably present-day Iraq

Isfandiyar fights with the Wolves, illustration to Shahnameh, cr. 1370, Tabriz, Persia

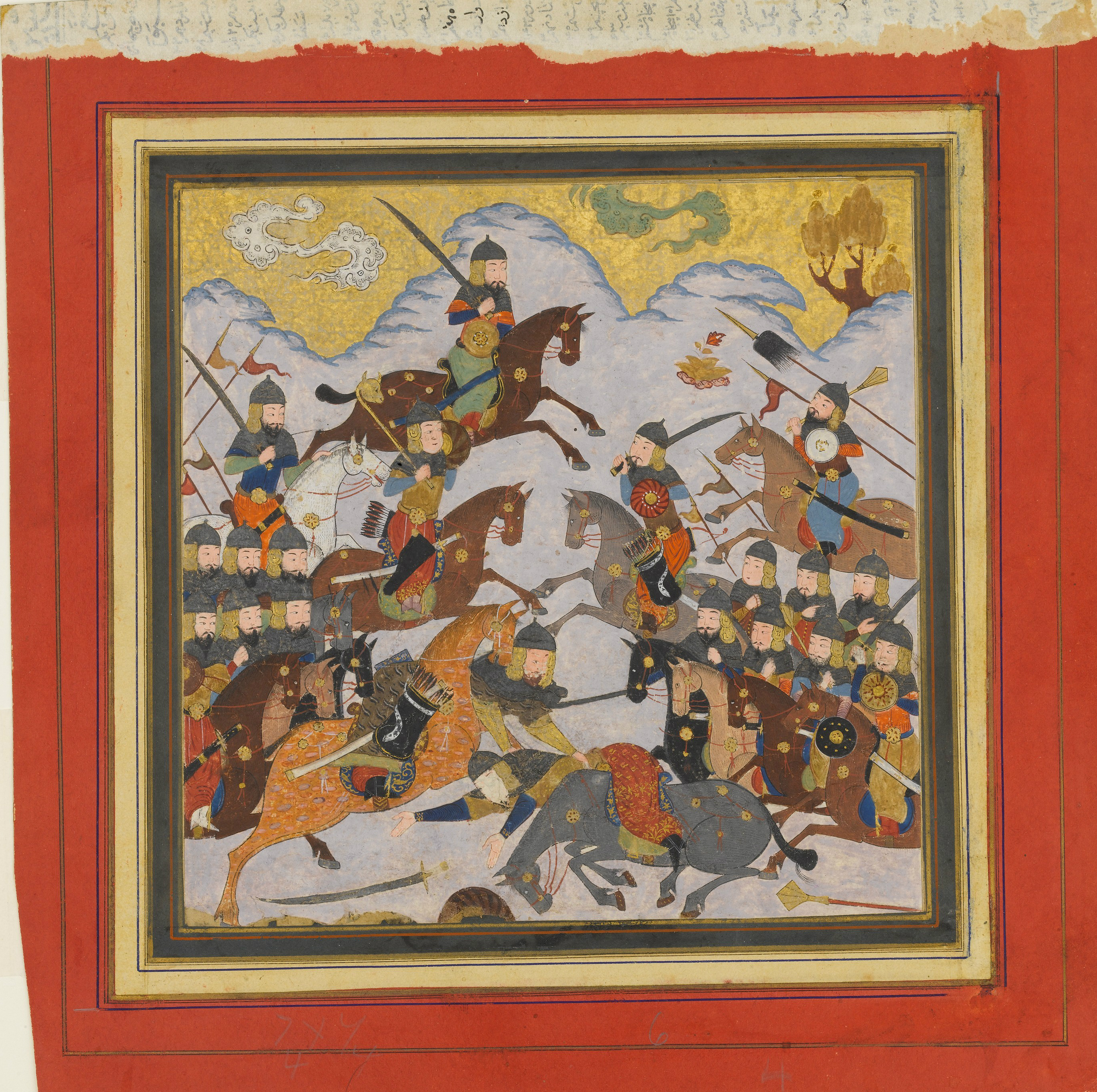

Battle between Chinese and Mongolian armies (1211), illustration of Jami' al-tawarikh, 1430, Sayf al-Vâhidî, Herat, Persia

Bahman Taking Revenge on the Sistanians', Compendium of Histories, ca. 1425, Herat, attributed to present-day Afghanistan

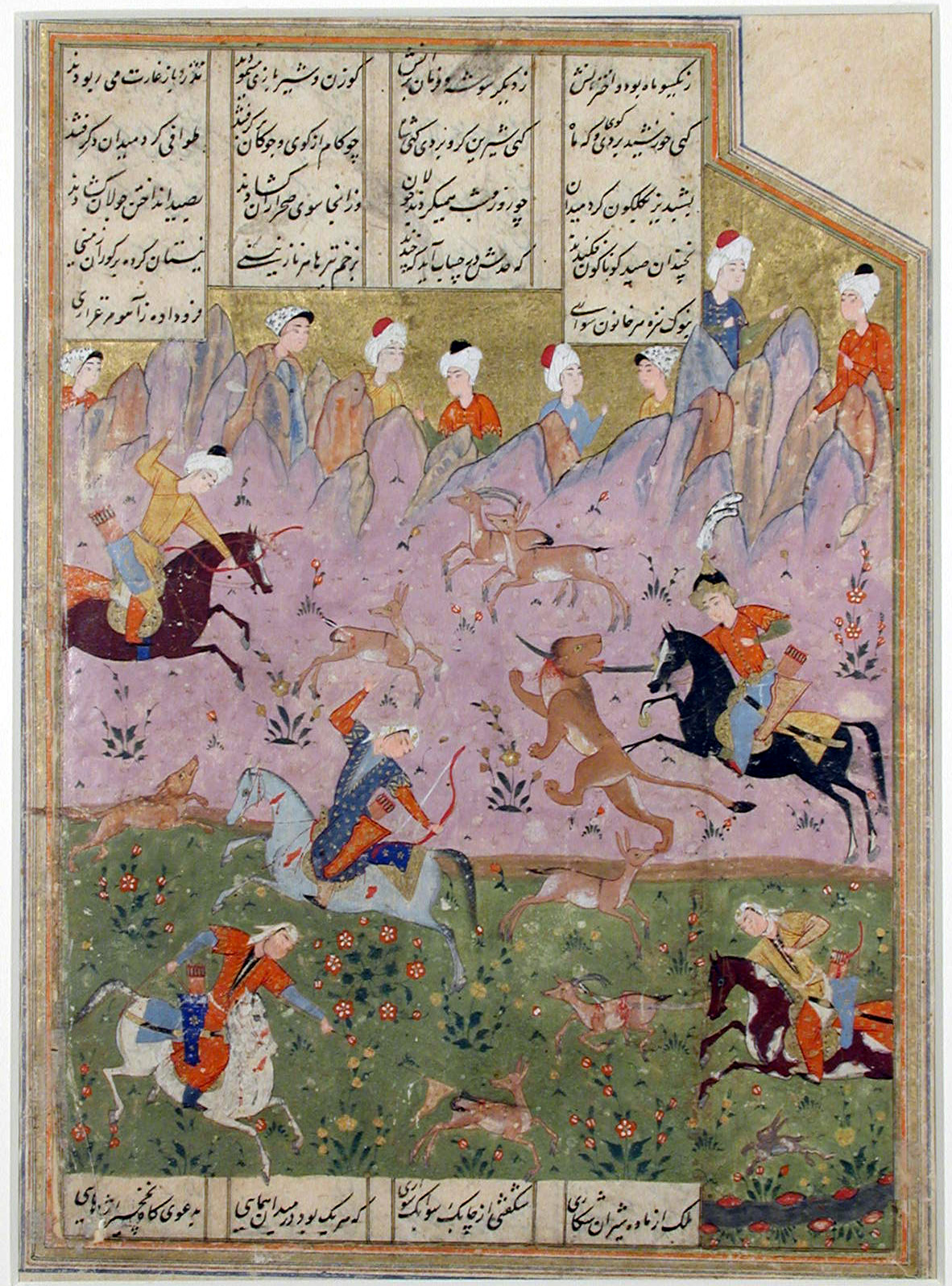

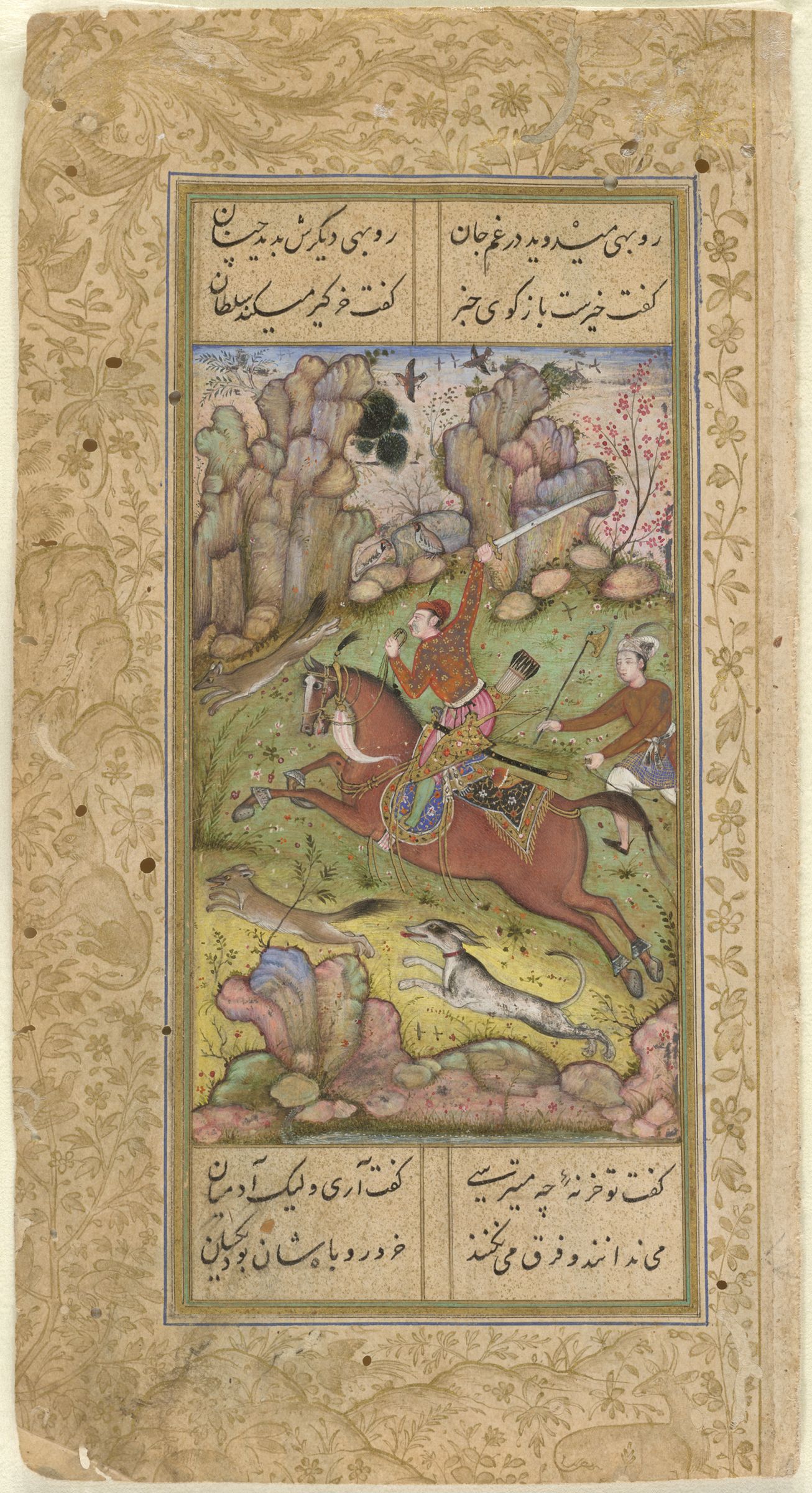

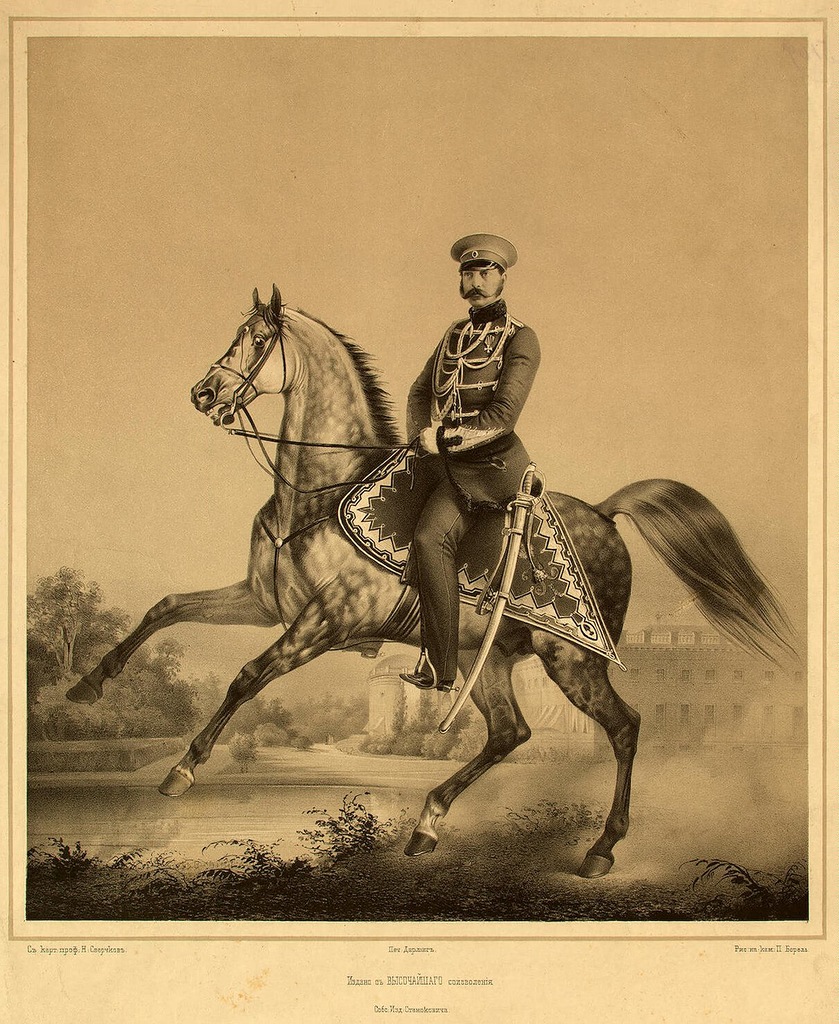

'Bahram Gur on the Chase', Seven Portraits of the Khamsa (Quintet) by Nizami of Ganja, ca. 1430, Herat, present-day Afghanistan

Masnavi of Jalal al-Din Rumi, 1488–89, attributed to Iran

Faramarz leads Borzu captive, illustration of Borzunameh, cr. 1500, Fars, Persia

Siyavush Plays Polo before Afrasiyab, illustration of the Book of Kings by Ferdawsi, cr. 1525–30, Shiraz, Persia

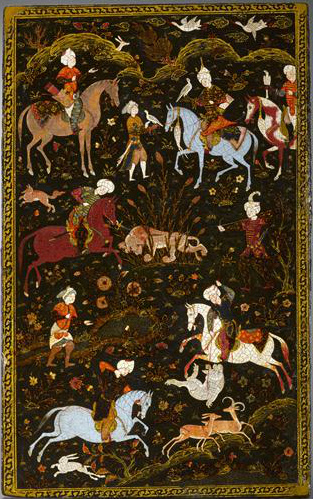

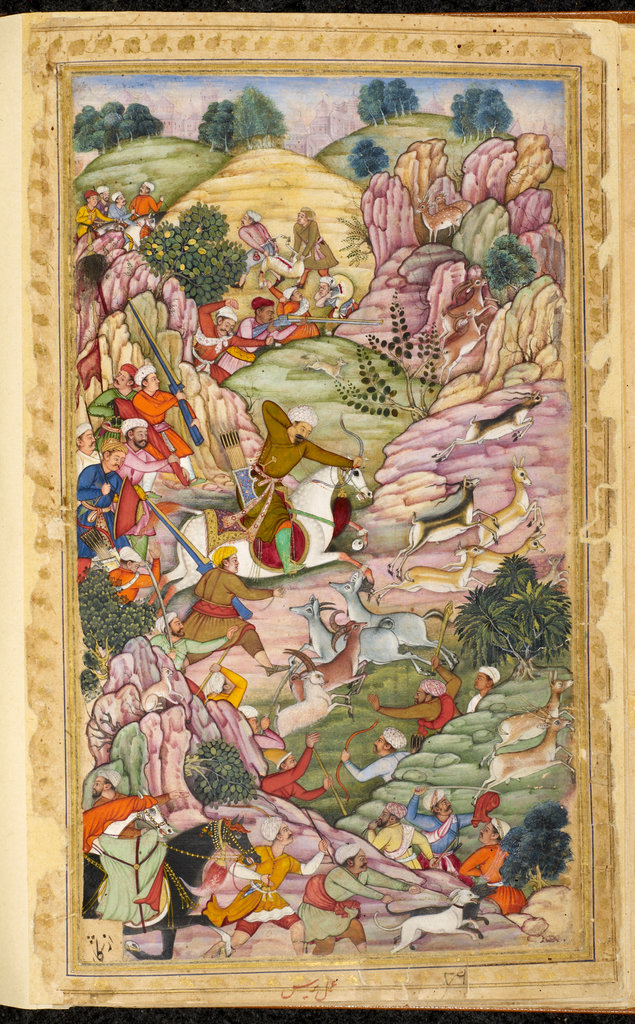

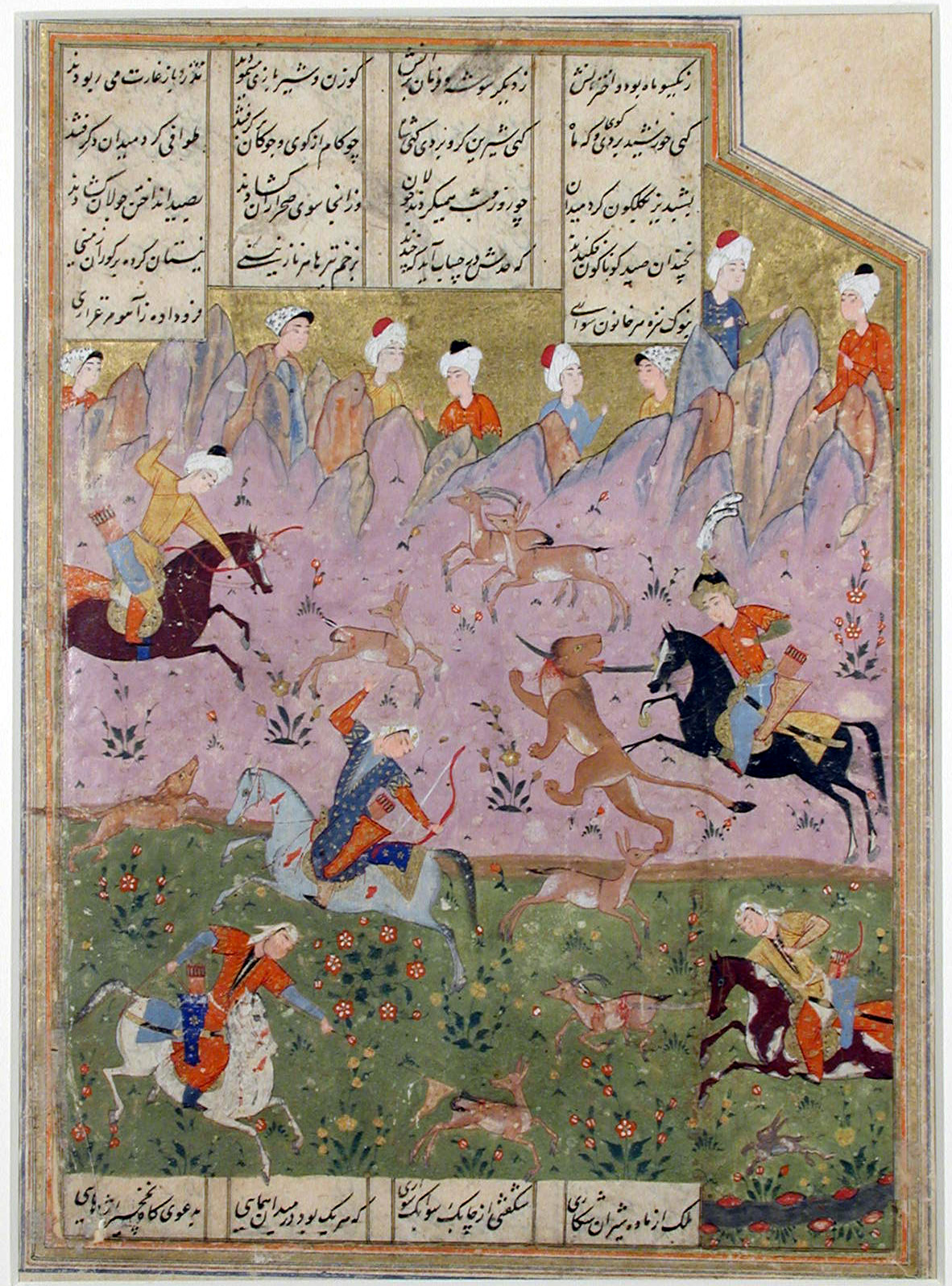

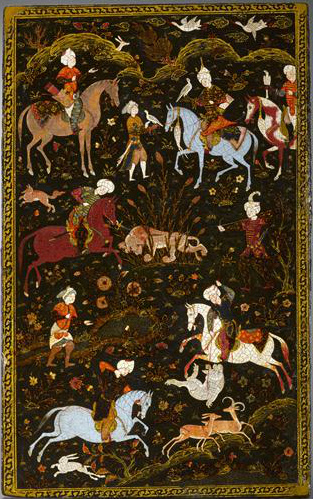

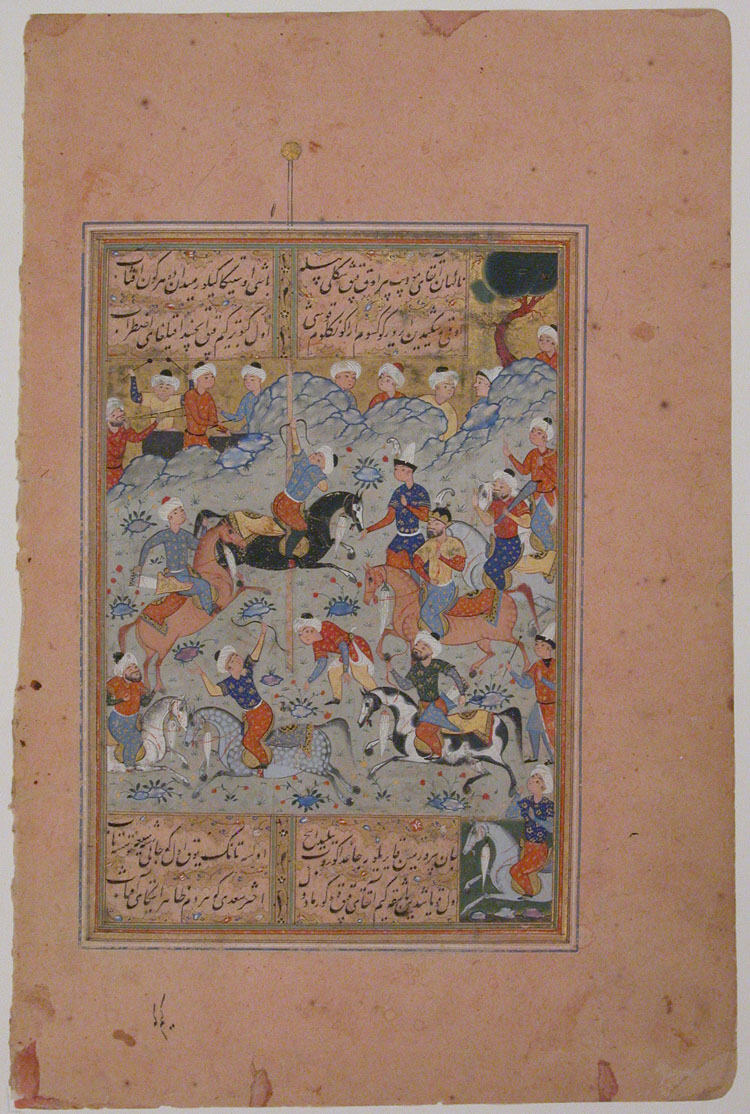

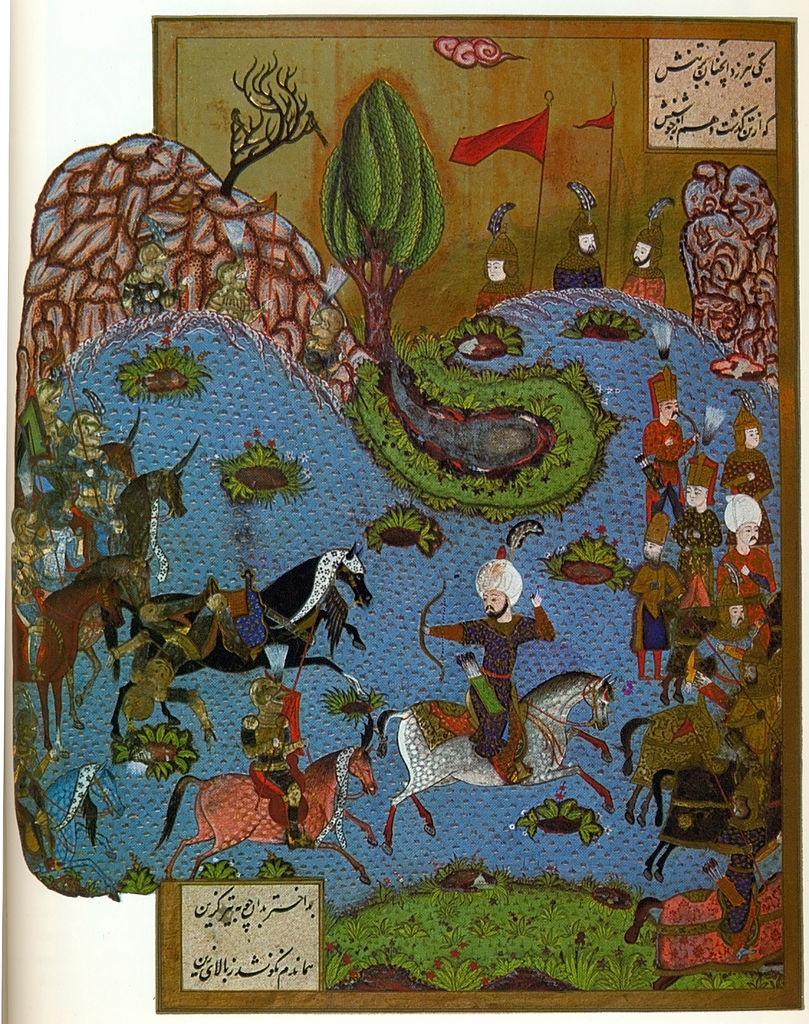

Hunting scene, illustration of the collection of poems of Ali-Shir Navai, cr. 1525-50, Shiraz, Persia

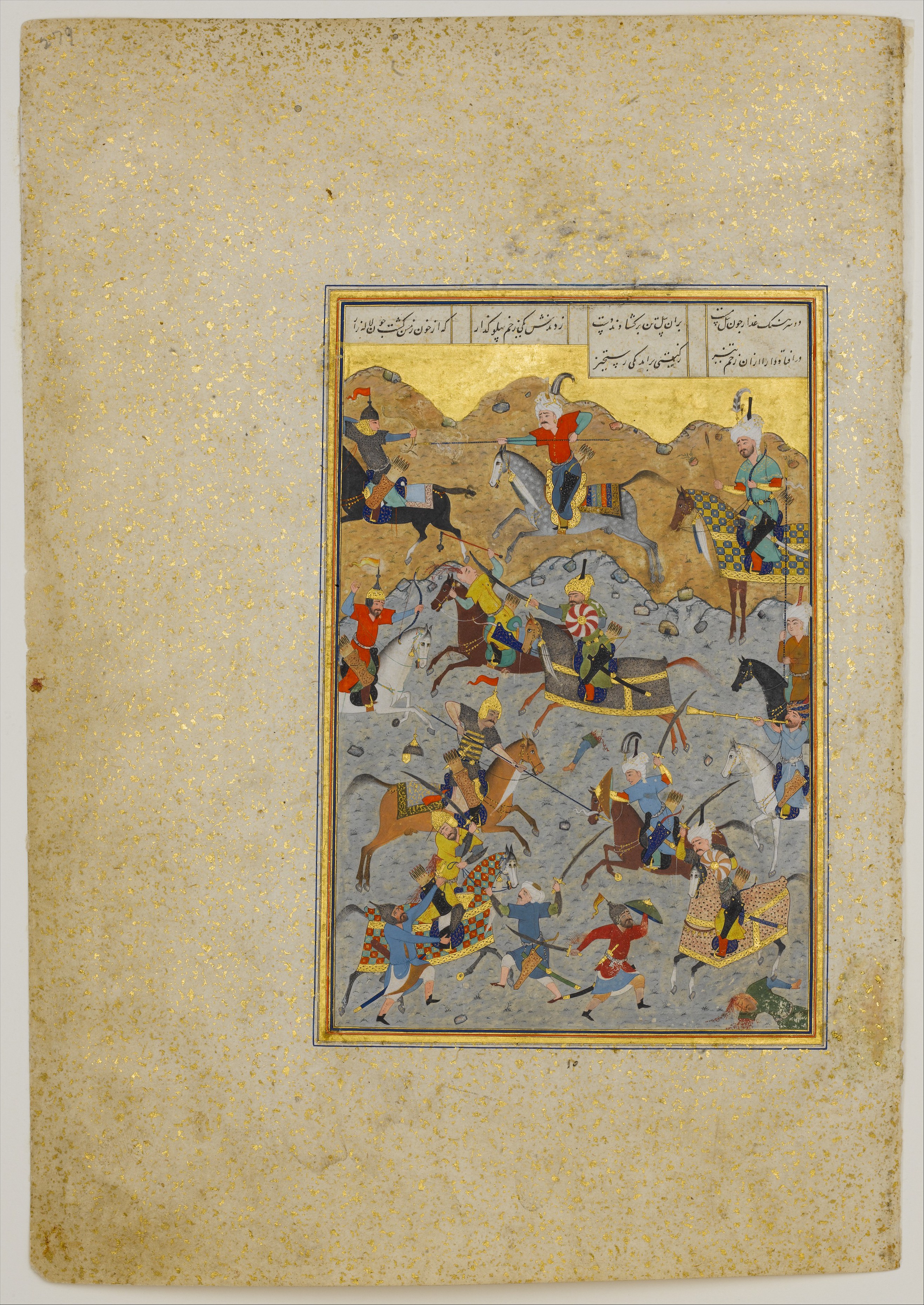

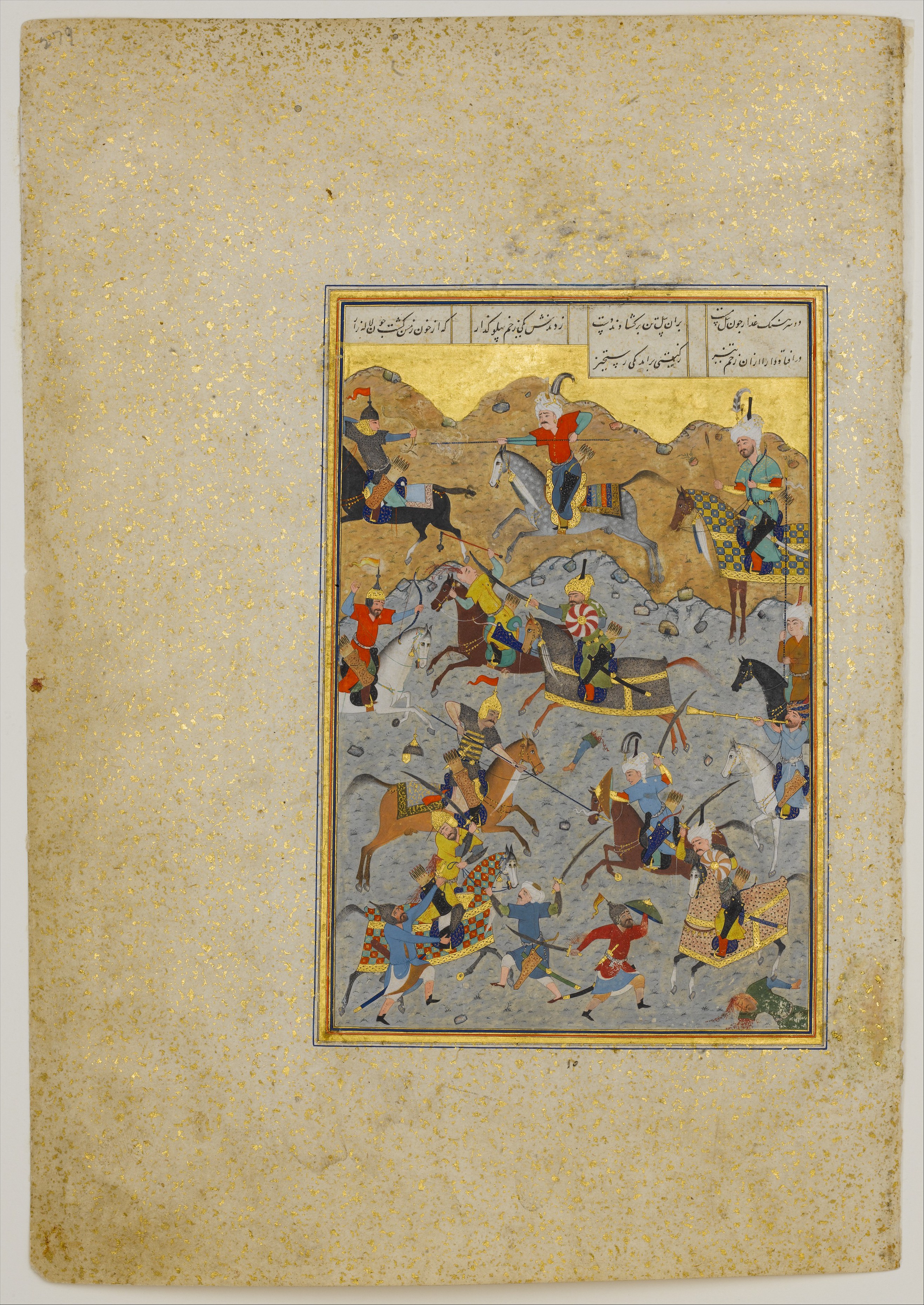

Sukhra's Victory over the Hephthalites in 486-8 (detail), illustration of Shahnameh, cr. 1530–35, Abu'l Qasim Firdausi, Tabriz, Persia

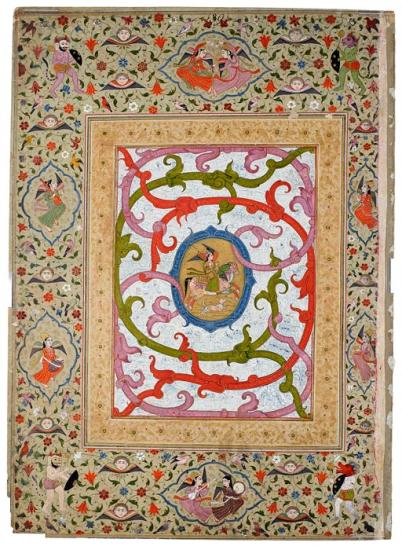

A manuscript page showing a hunter on horseback, cr. 1540, Muzaffar 'Ali, Tabriz, Persia (now Iran)

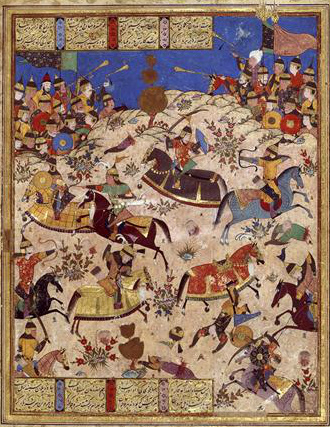

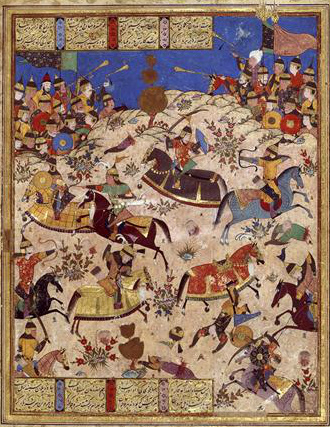

'Battle between Alexander and Darius', Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami of Ganja, 1524–25, Herat present-day Afghanistan

Two Mounted Warriors, an illustration of a codice, mid-16th century, attributed to Iran

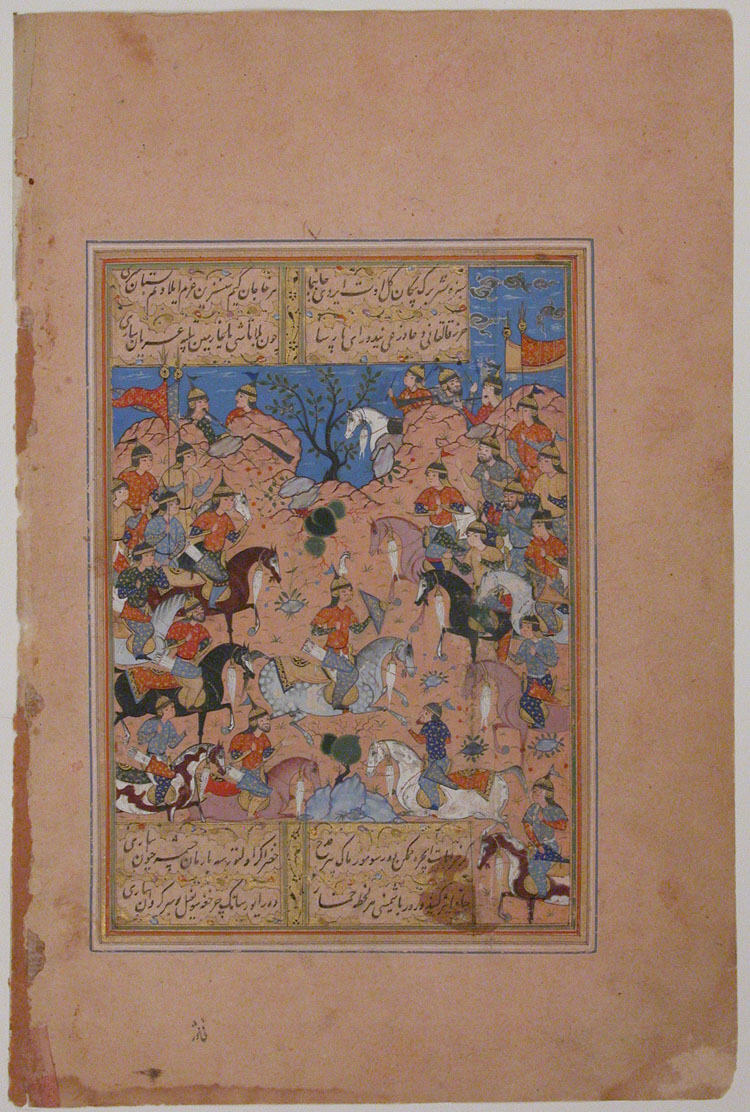

Battle Between Iranians and Turanians, illustration of the Book of Kings by Ferdawsi, cr. 1562–83, Shiraz, Persia

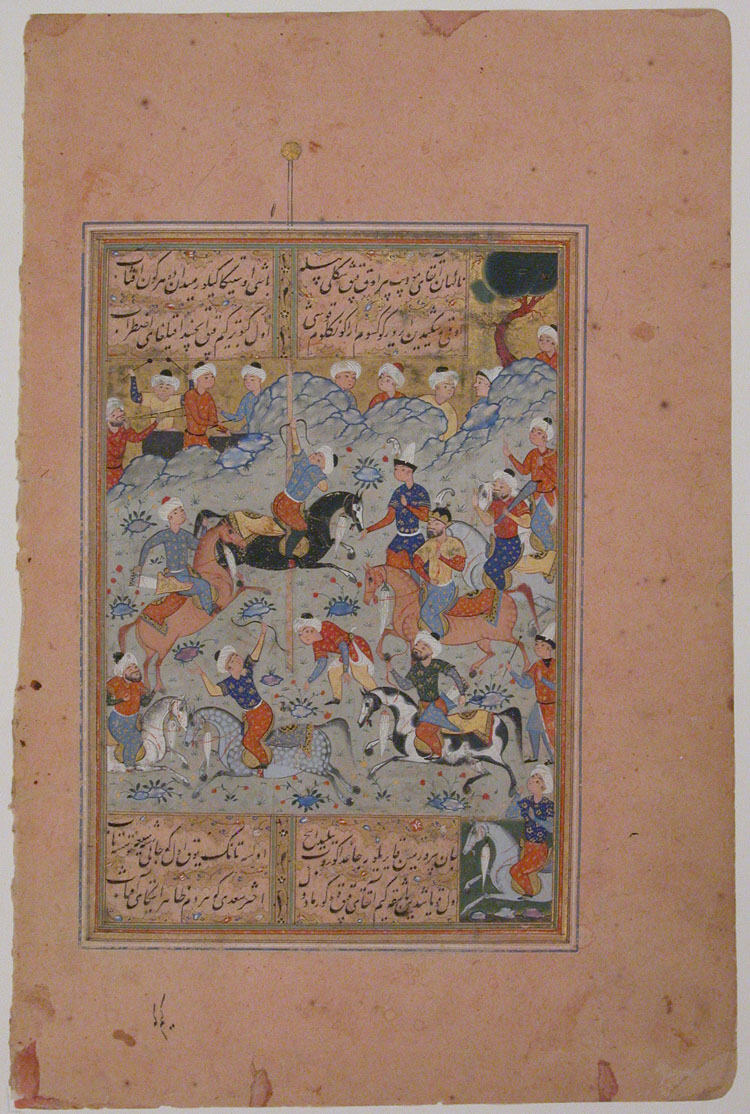

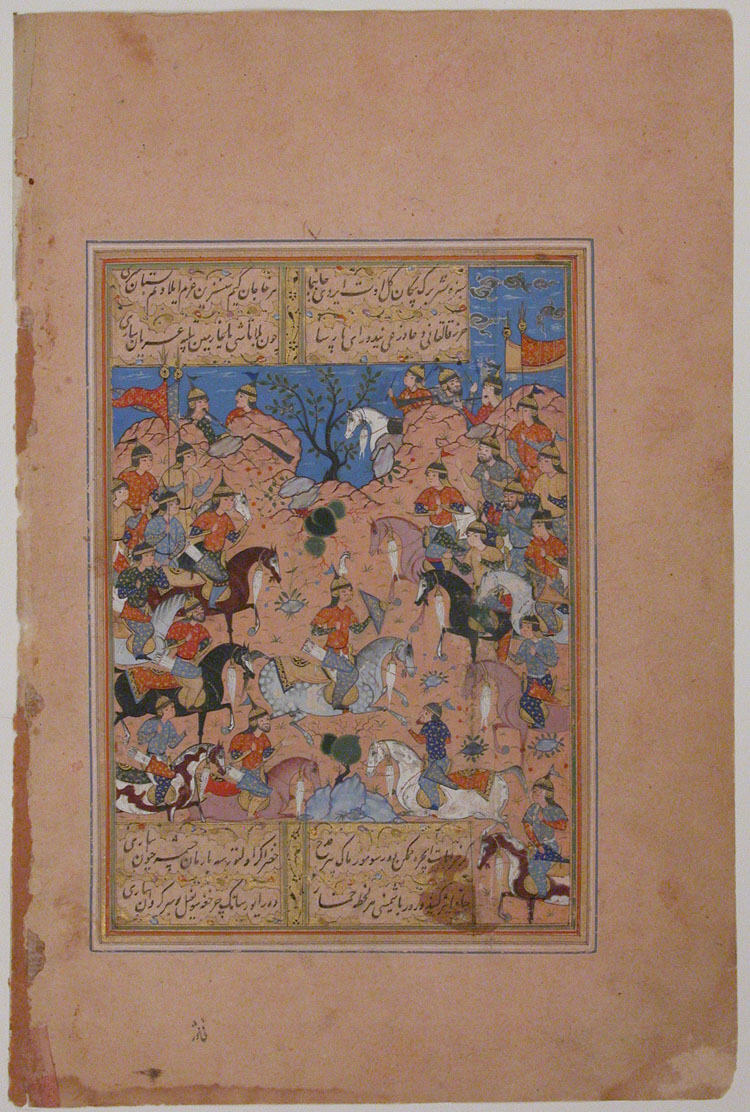

Battle between Manuchehre and Turanians, illustration of the Book of Kings by Ferdawsi, cr. 1567, Shiraz, Persia

Book cover showing courtly hunting scene, cr. 1560-88, Khorasan, Persia

'A Tournament at Arms', Folio from a Divan (Collected Works) of Mir 'Ali Shir Nava'i, 1580, attributed to Iran

'A Contest of Skill in Archery on Horseback', Folio from a Divan (Collected Works) of Mir 'Ali Shir Nava'i, 1580, attributed to Iran

Khosrow and Shirin hunting lions, illustration of Khamsa of Nizami, cr. 1580, Persia

Giv Charges into Battle against Piran, illustration of the Book of Kings by Ferdawsi, cr. 1589–90, Shiraz, Persia

Persian Textiles

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

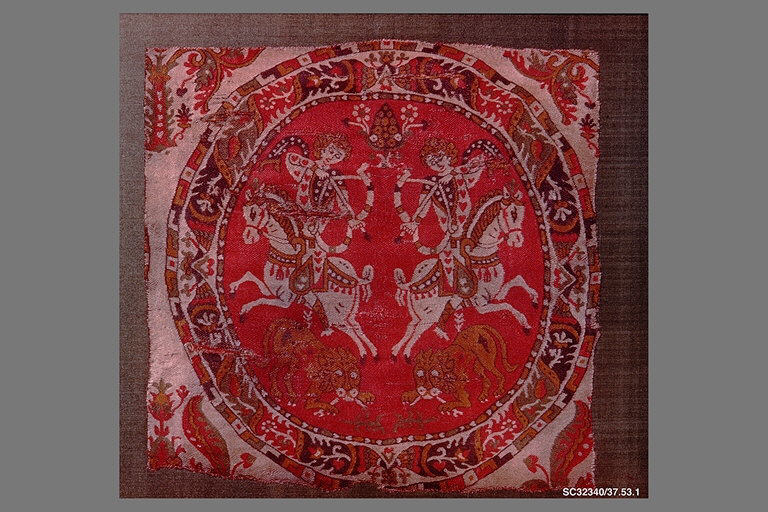

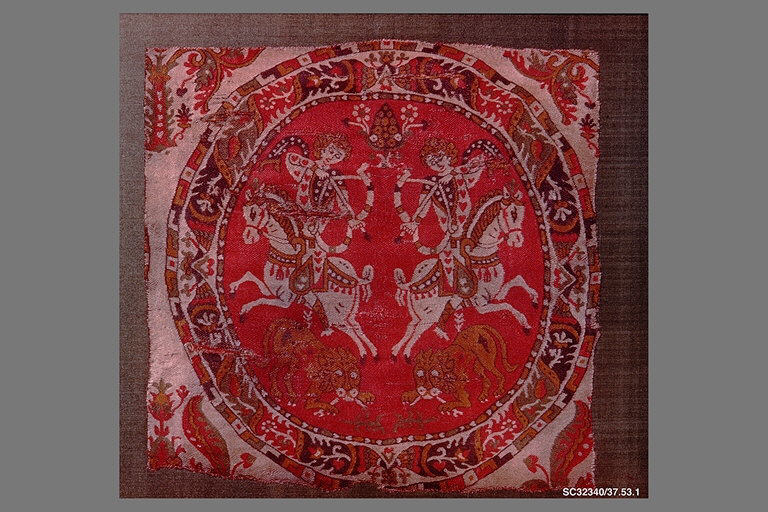

Silk Fragment, 10th–11th century, attributed to Iran

Velvet Panel with Hunting Scene, circa 1540, attributed to Iran, probably Tabriz

COMPARANDUM: Egyptian woven pattern, copy of an imported Sassanid silk, which itself was based on a fresco of king Khosrau I fighting against the Ethiopian forces in Yemen, ?

COMPARANDUM: Silk fragment, early 7th century, attributed to Syria

Persian Ceramics

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The bowl, 12th–13th century, attributed to Iran

The bowl, 12th–13th century, attributed to Iran

The bowl, 12th–13th century, attributed to Rayy, Iran

Rearing Horses of Indian Subcontinent, 12th – 19th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Hero Stones, 12th – 16th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

A hero stone is a memorial commemorating the honorable death of a hero in battle. Erected between cr. 5th-18th centuries, hero stones are found all over India. According to the MAP Academy, hero stones serve as a crucial part of a spectrum of art historical material related to the performance and commemoration of military activity. They could be compared to funeral stelae, sarcophagi and victory commemoration monuments of Persia and antique world cultures.

Hero stone, cr. 1115, Kedareshvara temple, Balligavi, Shimoga district, Karnataka state, India

Hero stone, 13th century, Shivappa Nayaka palace, Shivamogga city, Karnataka state, India

Hero stone, 16th century, Shivappa Nayaka palace, Shivamogga city, Karnataka state, India

COMPARANDUM: The Çan Sarcophagus, detail of Persian horseman spearing fallen footsoldier, 400-375 BC, village of Altıkulaç, near Çan, modern-day Turkey

COMPARANDUM: Tomb sculpture of Dexileos, cr. 394 BC, Attic

COMPARANDUM: Sarcophagus of the type called 'Sydamara sarcophagi', 2nd half of the 3rd century, ancient Middle East

COMPARANDUM: Marble votive tablet of the Thracian Horseman, 3rd century AD

COMPARANDUM: Tombstone for Roman cavalryman Comnisca, 1st century AD, discovered in Strasbourg, France

COMPARANDUM: Mausoleum of the Julii, cr. 40 BC, Glanum, part of Roman Republic (now Saint-Rémy de Provence, France)

COMPARANDUM: North face relief, mausoleum of the Julii, cr. 40 BC, Glanum, part of Roman Republic (now Saint-Rémy de Provence, France)

COMPARANDUM: Arch of Constantine and Colosseum in the background, 315, Rome

COMPARANDUM: Arch of Constantine (detail), 315, Rome

A Mural, 17th century

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The mural presented in this section is part of the Battle of Bhuchar Mori memorial shrine. This battle was fought in 1591 and resulted in the victory of Mughols. The style of the mural is supposed to be traditional, but, unfortunately, I could not find any comparable memorials in India. Curiously, some Italian frescoes look very similar.

Ajaji on the horse attacking Mirza Aziz Koka on an elephant, Bhuchar Mori memorial shrine mural, 16th-century art, Mughal school, Dhrol, Jamnagar district, Gujarat, India

COMPARANDUM: Clash between an Arab knight and a Christian knight during the Crusades, fresco, 12th century, Patriarchal Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, Aquileia, Italy

Cronicles Illustrations, 16th – 19th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

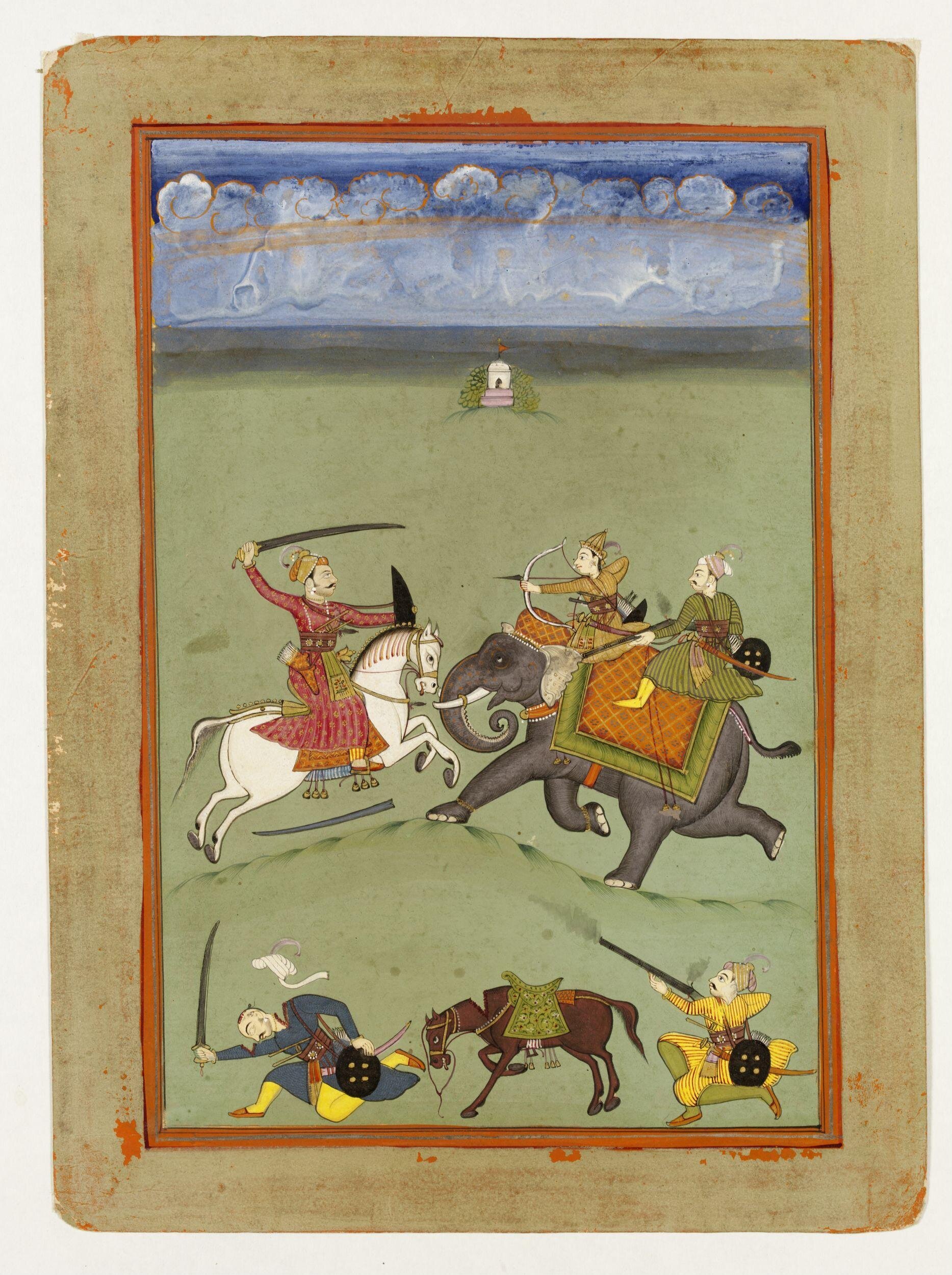

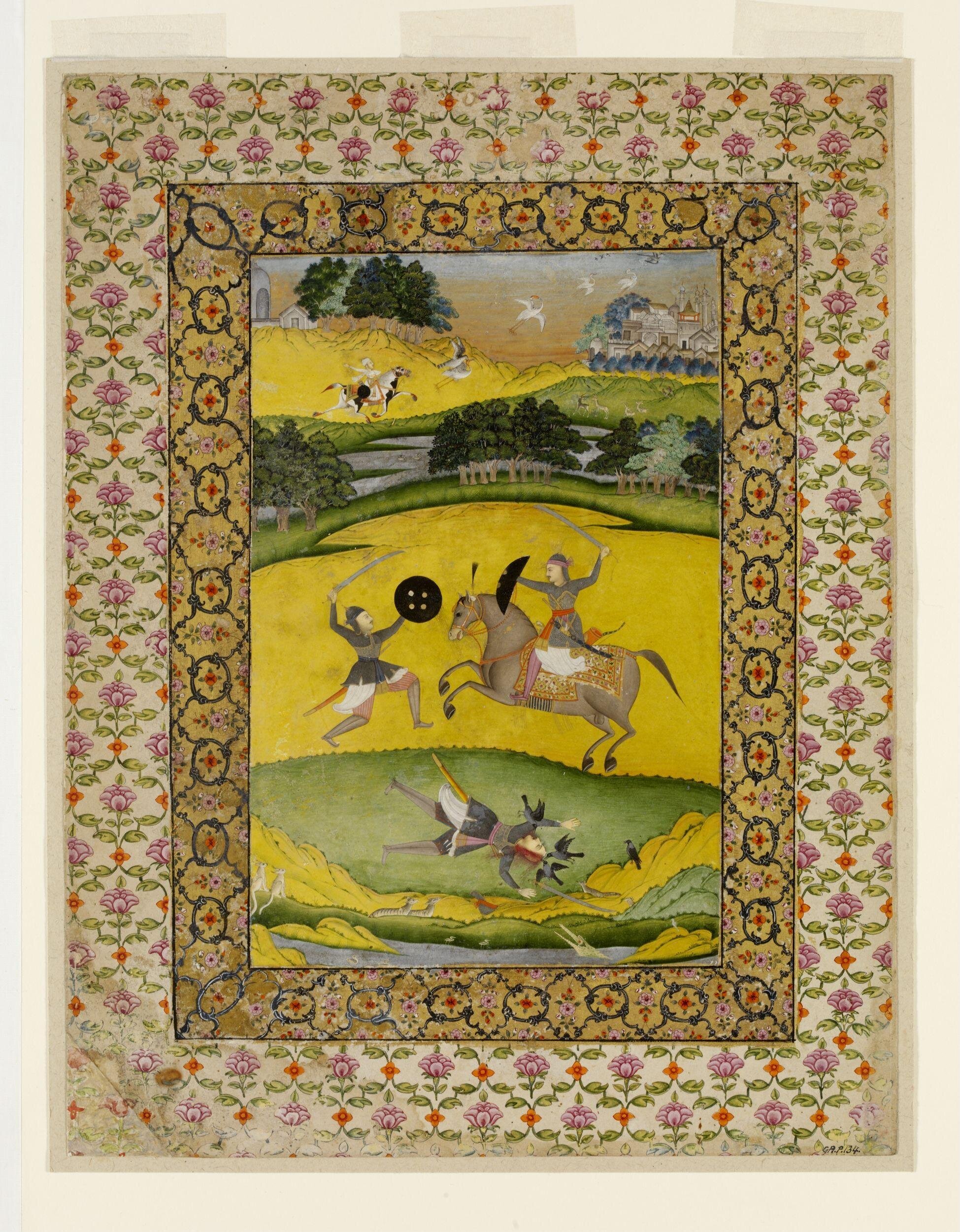

Mughal painting is a particular style of South Asian, particularly Indian, painting. It emerged from the Persian miniature painting and developed in the court of the Mughal Empire (1526 – 1857). The Mughal emperors were Muslims and they are credited with consolidating Islam in South Asia, and spreading Muslim (and particularly Persian) arts and culture as well as the faith.

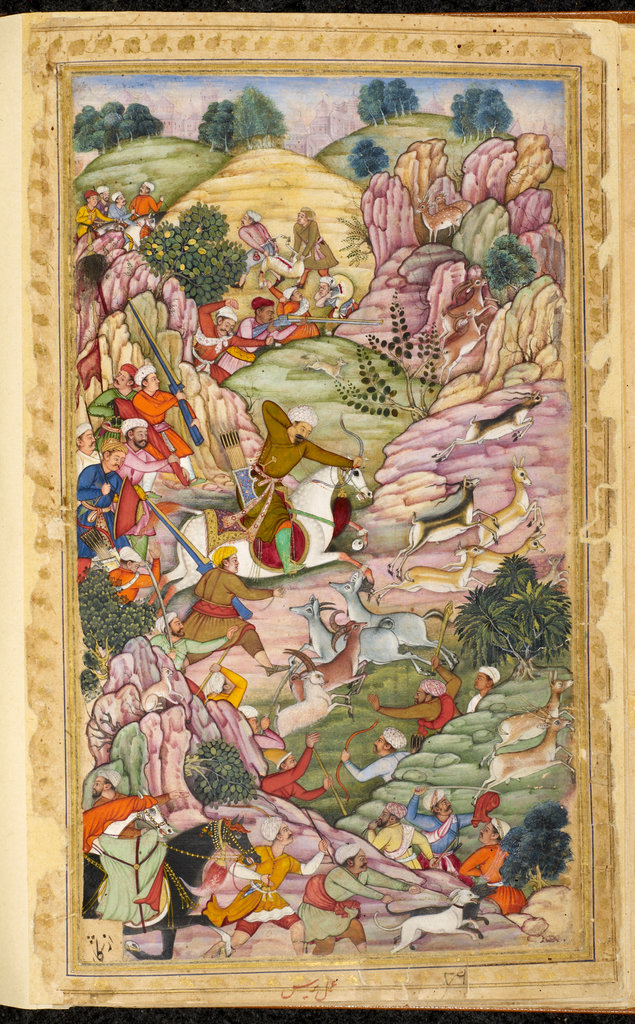

Early Mughal illustrations emulate the Persian illustrations of Shahnameh. The major difference is that they illustrate the chronicles of reign of recent and contemporary Mughal emperors.

- Baburnama is the memoirs of Ẓahīr-ud-Dīn Muhammad Babur (1483–1530), founder of the Mughal Empire and a great-great-great-grandson of Timur.

- Akbarnama is the official chronicle of the reign of Akbar, the third Mughal Emperor (r. 1556–1605), commissioned by Akbar himself and written by his court historian and biographer, Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak.

- Padshahnama (Chronicle of the Emperor Shah Jahan) is a group of works written as the official history of the reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. Unillustrated texts are known as Shahjahannama, with Padshahnama used for the illustrated manuscript versions. Mirza Shihab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram (1592 – 1666), also known as Shah Jahan I (in Persian, this means ’King of the World’), was the 5th emperor of the Mughal Empire, reigning 1628 – 58. Under his emperorship, the Mughals reached the peak of their architectural achievements and cultural glory.

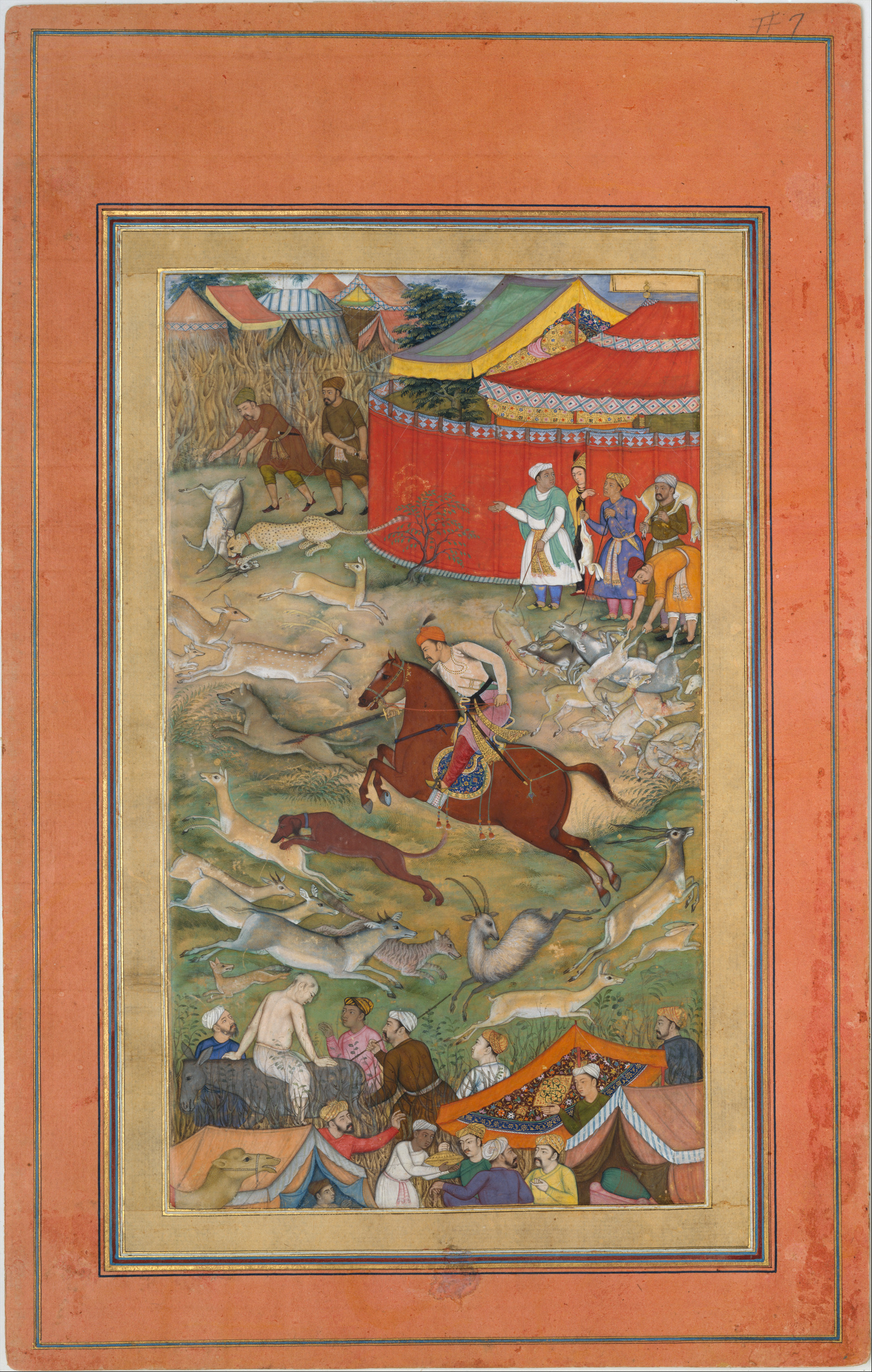

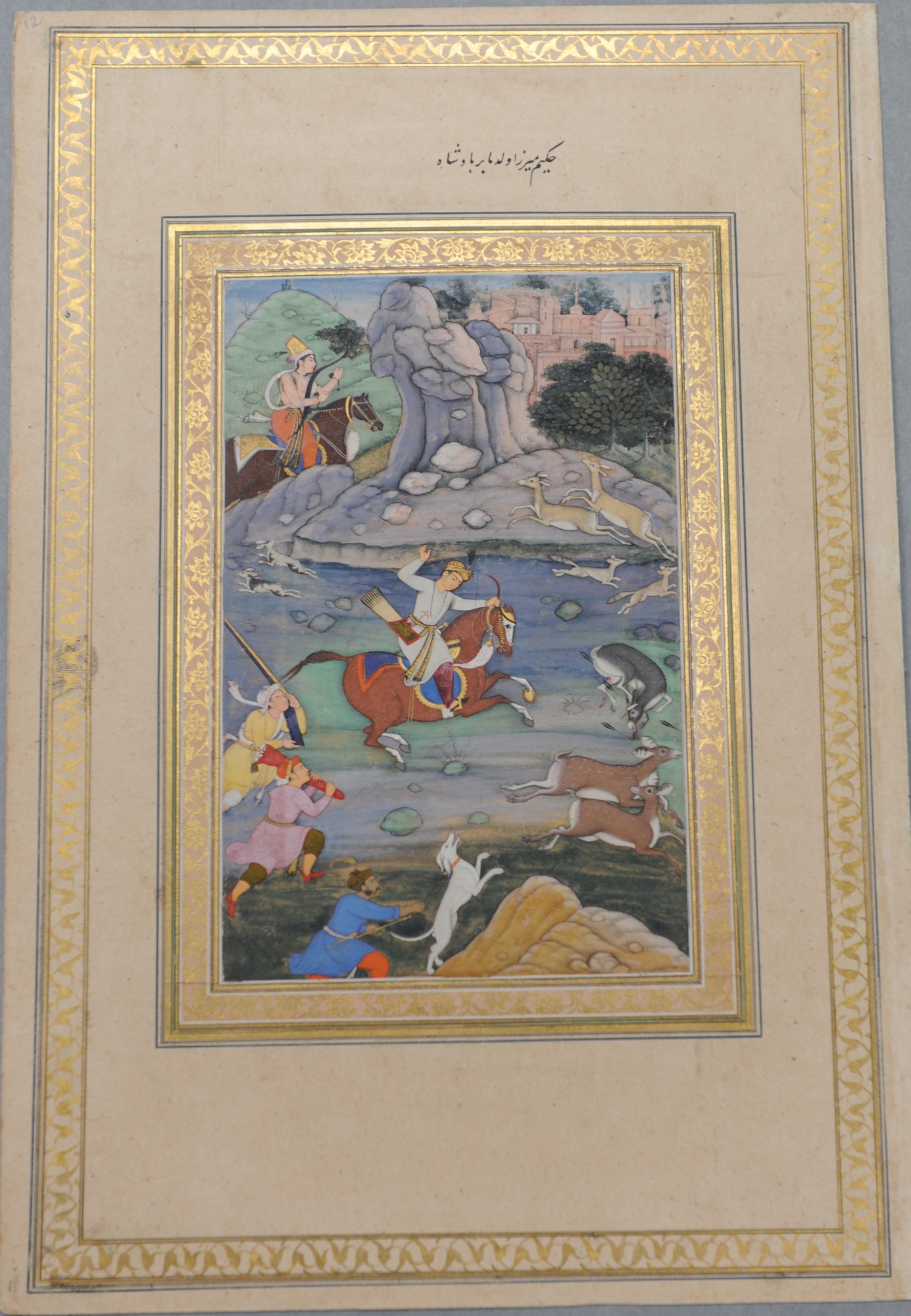

Akbar Hunting, illustration of History of Akbar by Abul-Fazl ibn Mubarak, late 16th century, Lahore, Mughal Empire

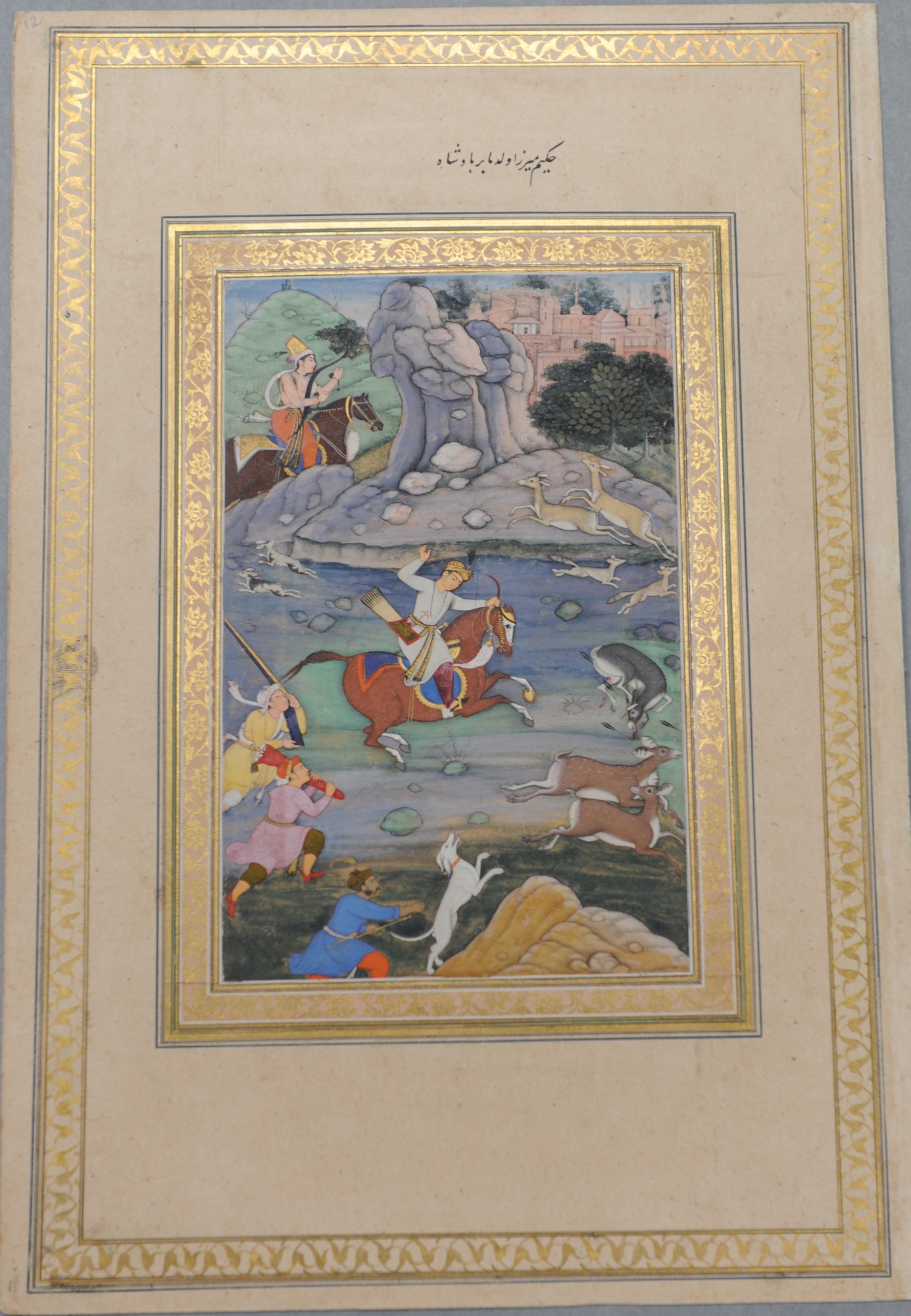

Babur hunting deer between ‘Ali Shang and Alangar near Kabul, cr. 1590, Paras, India

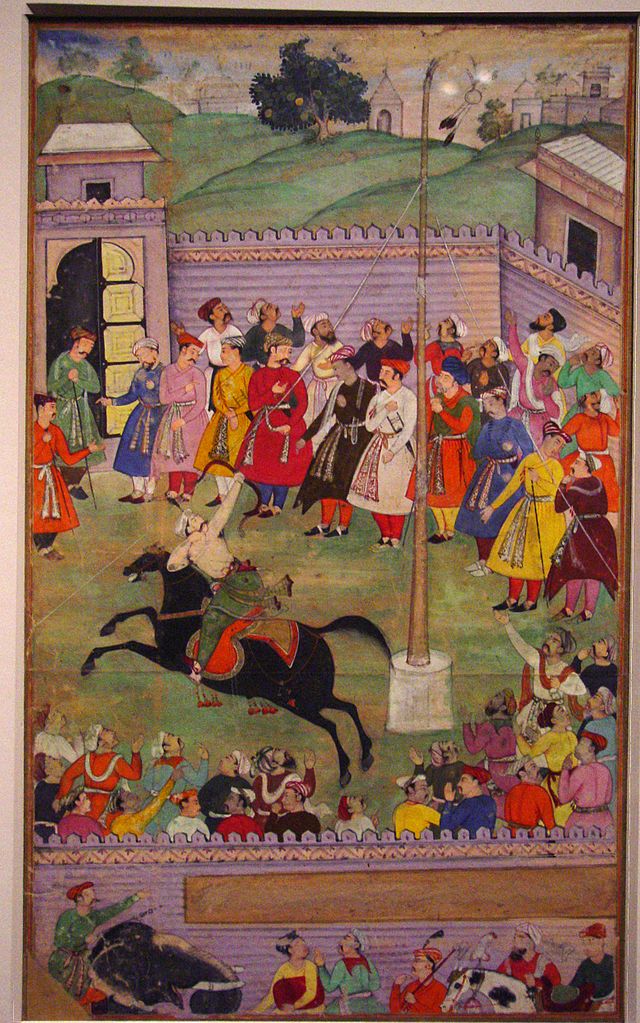

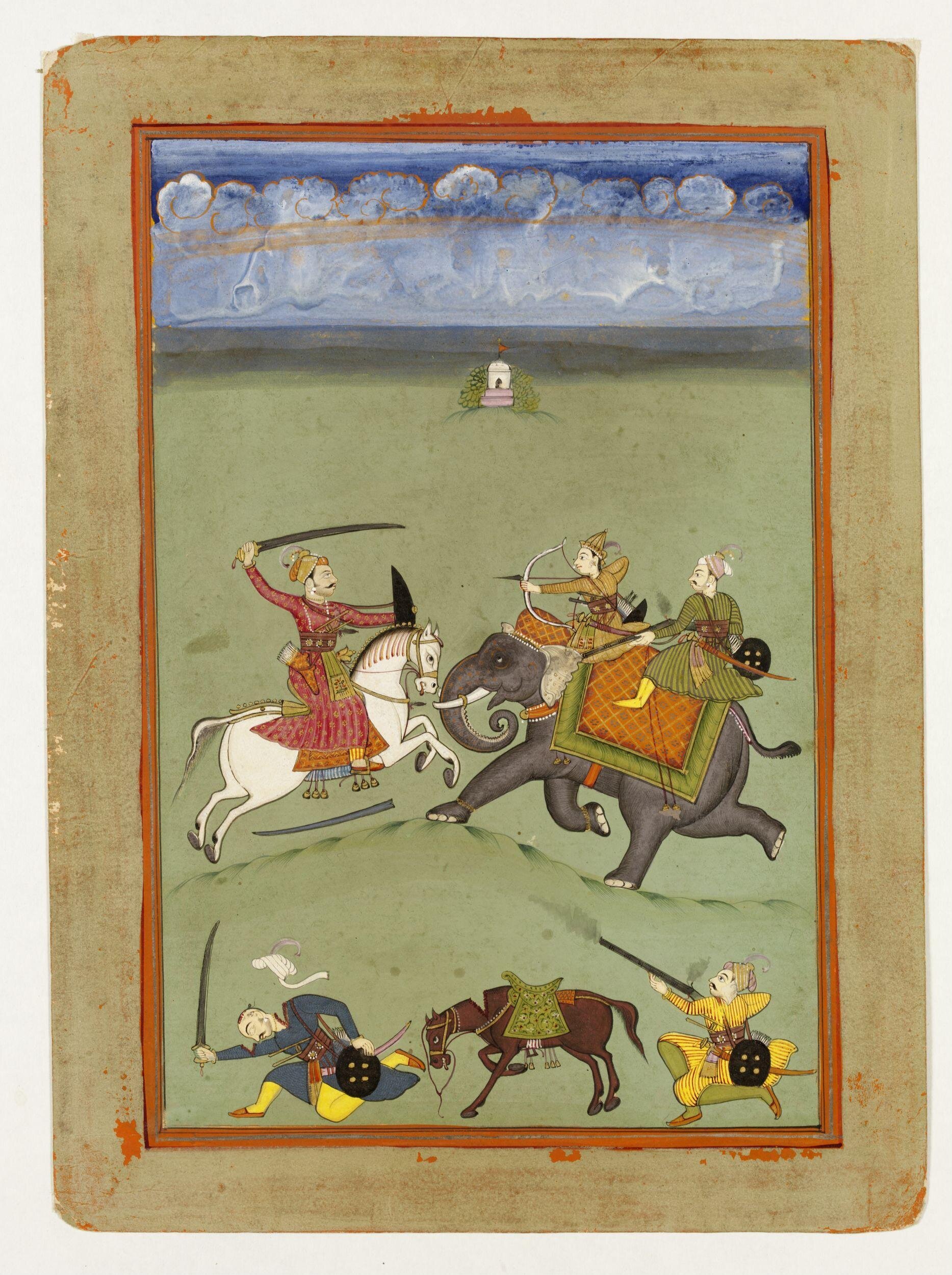

The victory of Khan Zaman (Ali Quli Khan) over the Afghans on the banks of the river Jumna in 1561, illustration of Akbarnama (Book of Akbar), cr. 1590-95, Kanha and Khiman Sangtarash, Mughal Empire

Hamid Bhakari Punished by Akbar, Folio from an Akbarnama, cr. 1604, attributed to Manohar, India

The Battle of Shahbarghan, illustration of Padshahnama by Abdul Hamid Lahori, 1646-1700, Mughal Empire

Prince Awrangzeb facing a maddened elephant named Sudhakar (7 June 1633), Padshahnamah, cr. 1635 - 1640, Mughal school

Religious Non-Islamic Texts Illustrations, 16th – 19th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The other major cluster of works are the illustrations to Indian epic poetry and religios texts

Indian Islamic Illustrations

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Rustam Seizes Afrasiyab by the Girdle and Lifts him from the Saddle, illustration of the Book of Kings by Ferdawsi, cr. 1430–40, India (?)

The Fox's Fear, an illustration from a manuscript of the Divan (Collection of Works) of Anvari, 1588, Mughal school, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan

Hamza's son Ibrahim rides into a battle on a demon-drawn chariot, Hamzanama, cr. 1558-73, India

Disperced Book Illustrations, ?

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

A friend of a friend is making his living by extracting the valuable illustrations from old books and selling them as stand-alone images. It appears that his business is not the invention of the 21st century; something similar was practiced on Indian subcontinent a few centuries ago.

Archery Competition, cr. 1600, ?, Mughal Empire

A hunting scene, very early 17th century, Mughal

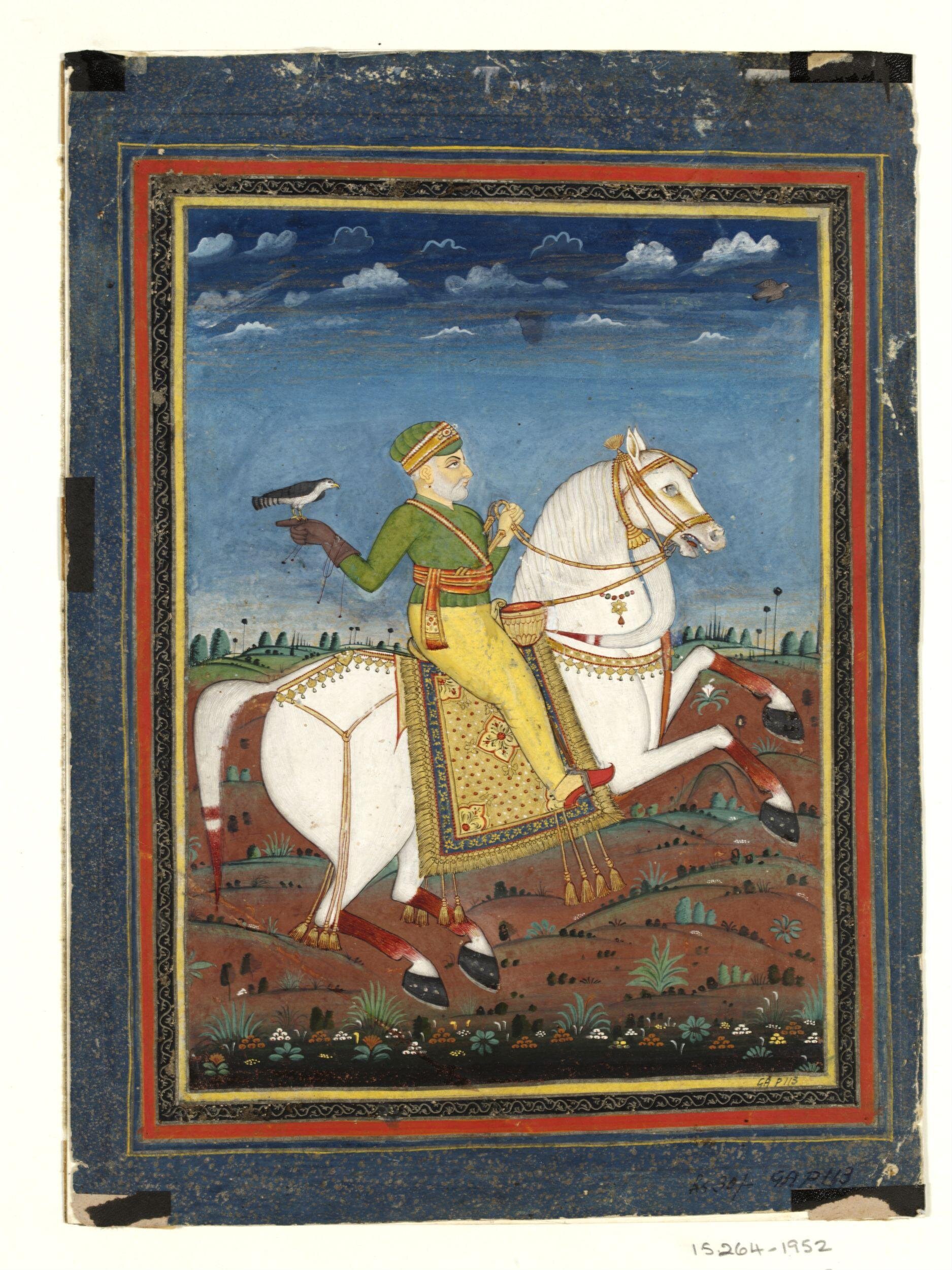

Cliché Mughal Equestrian Portraits

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

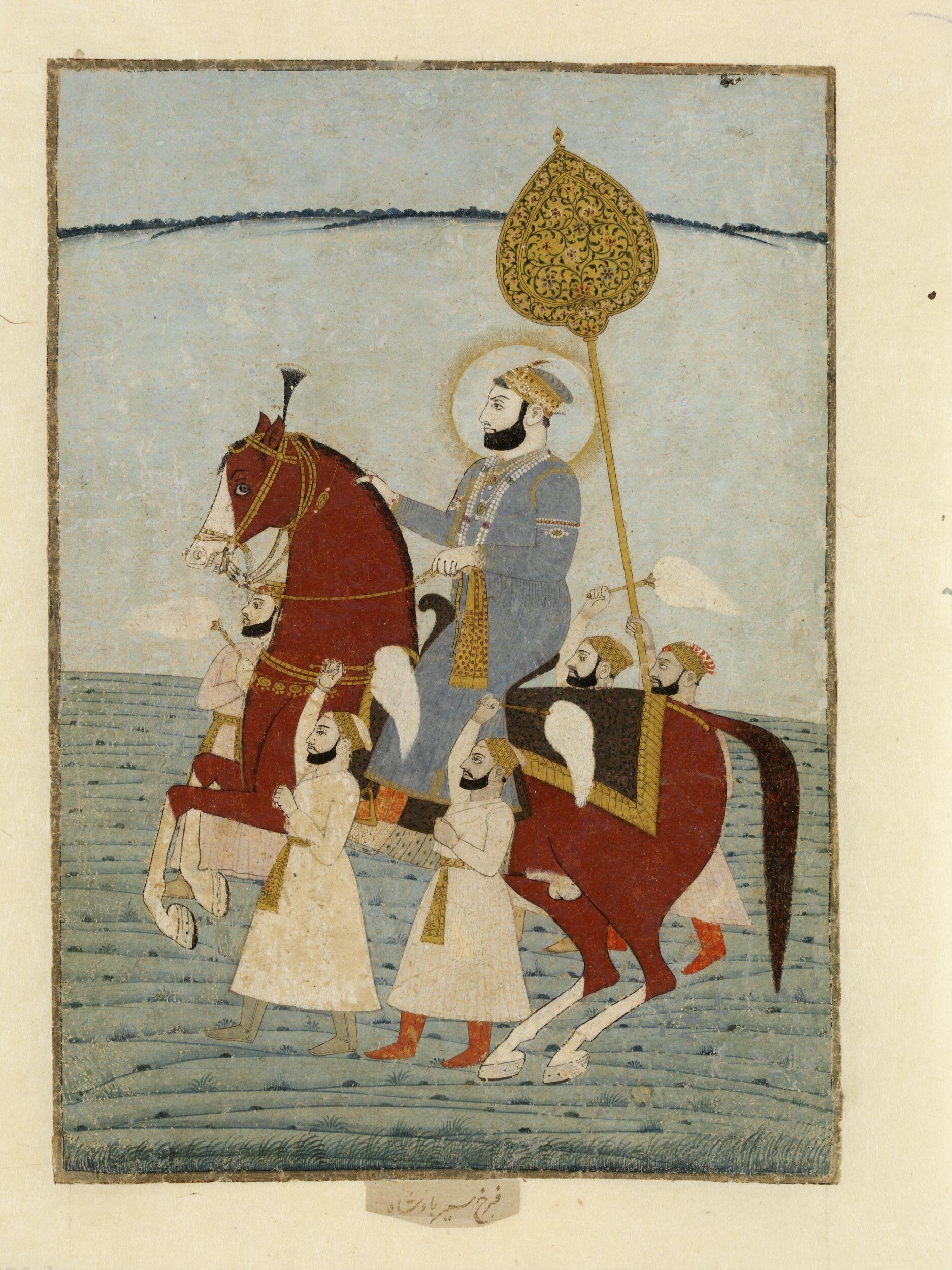

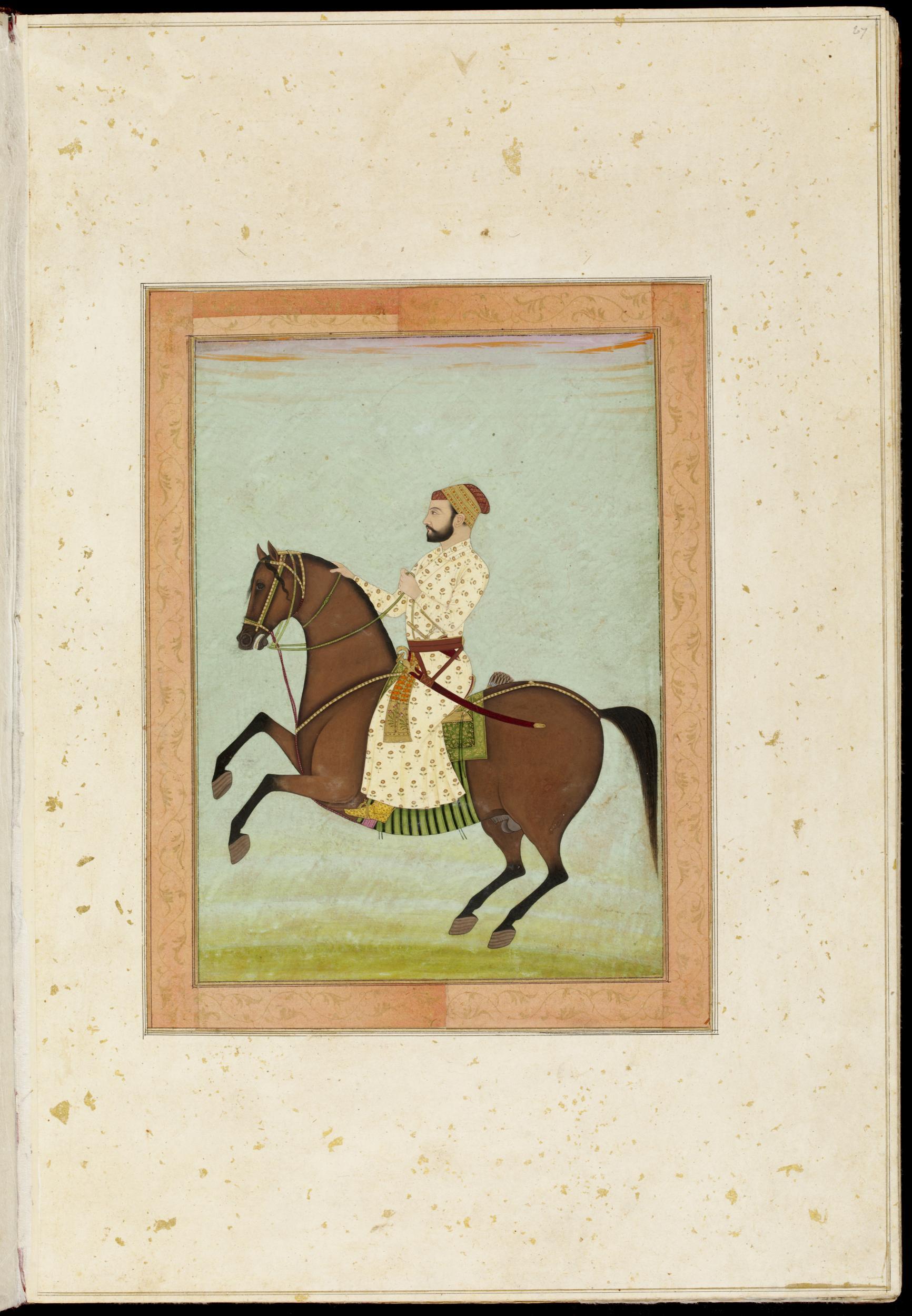

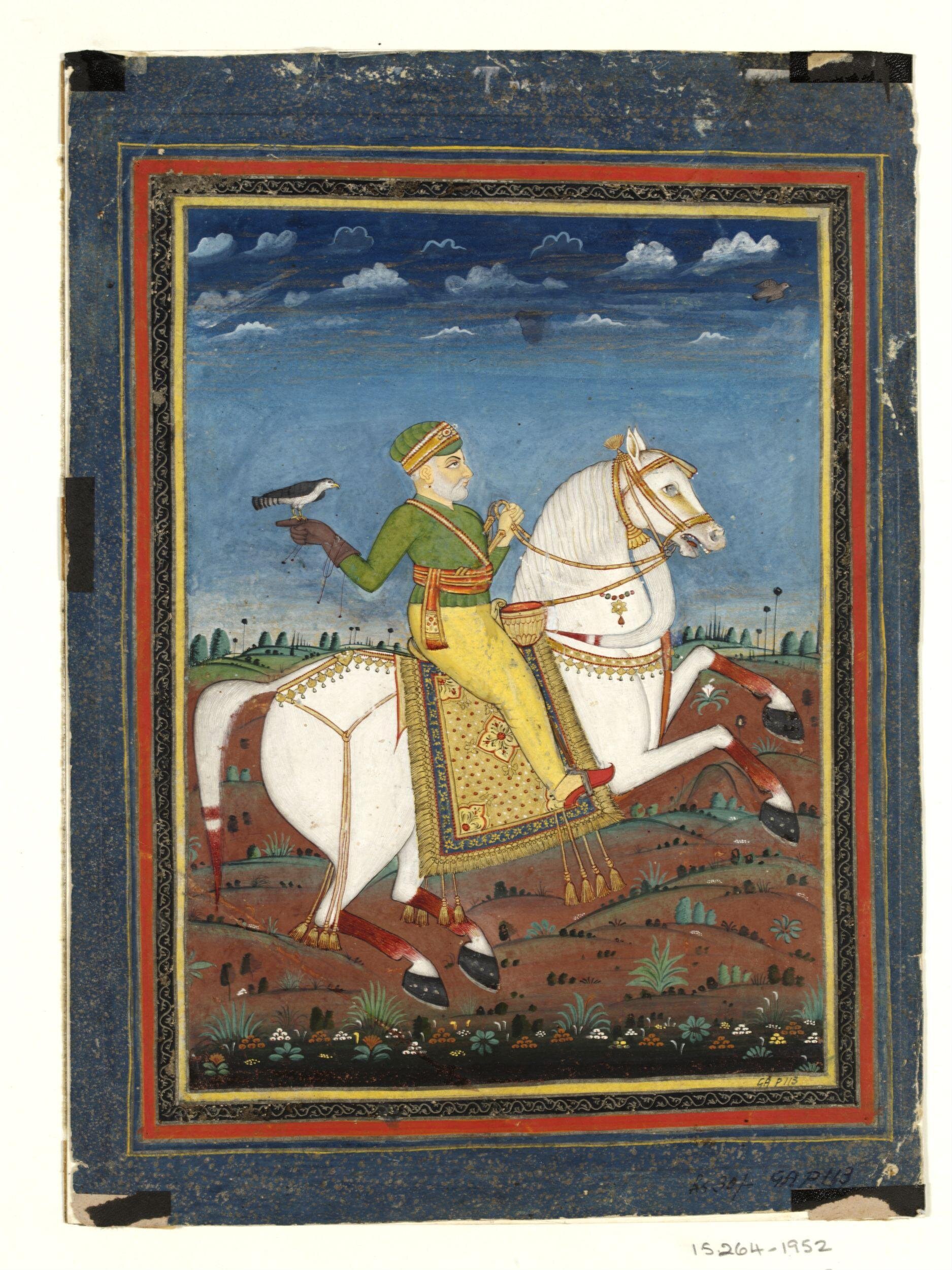

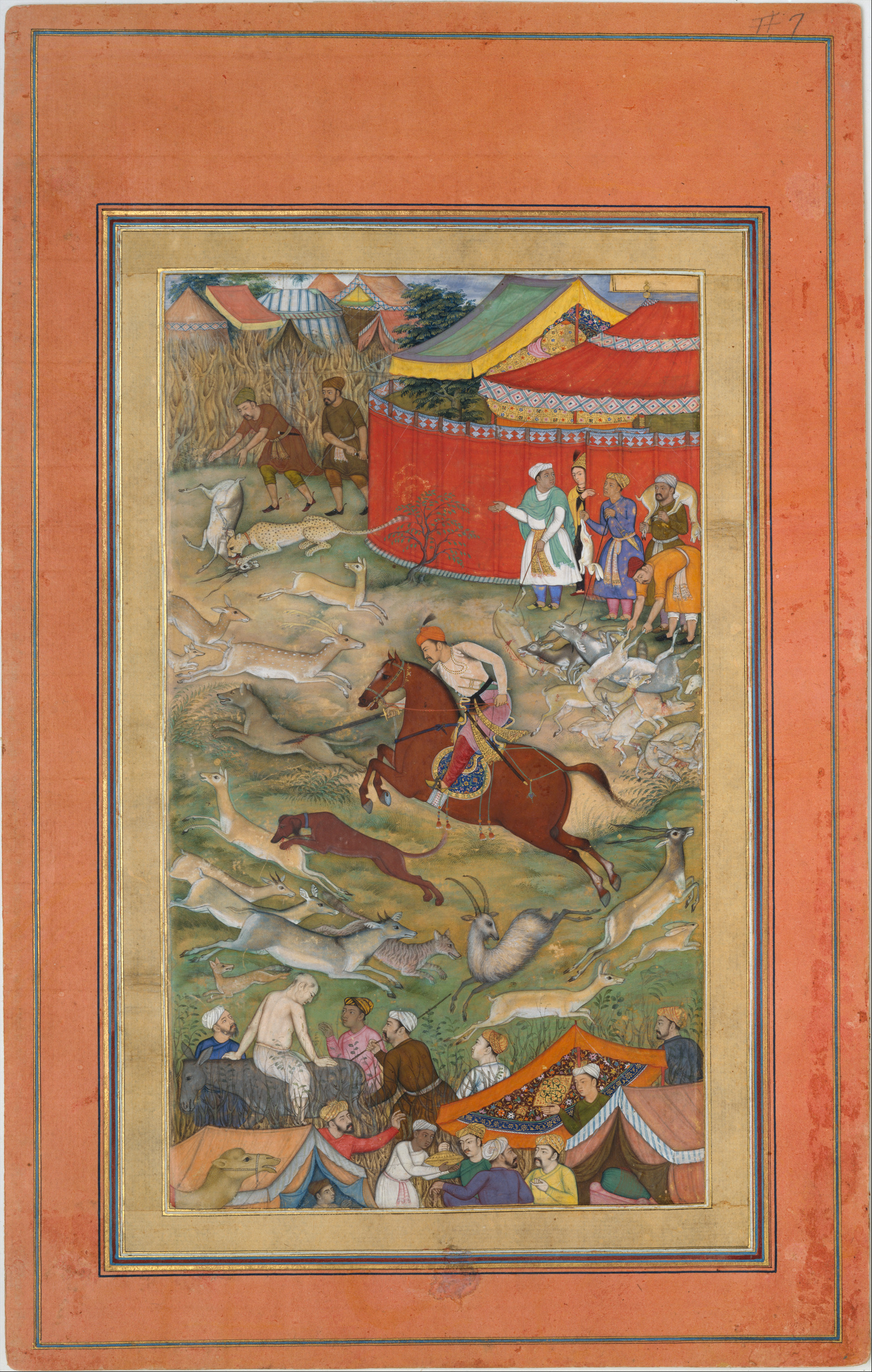

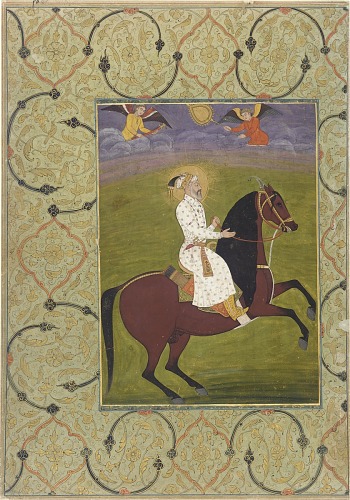

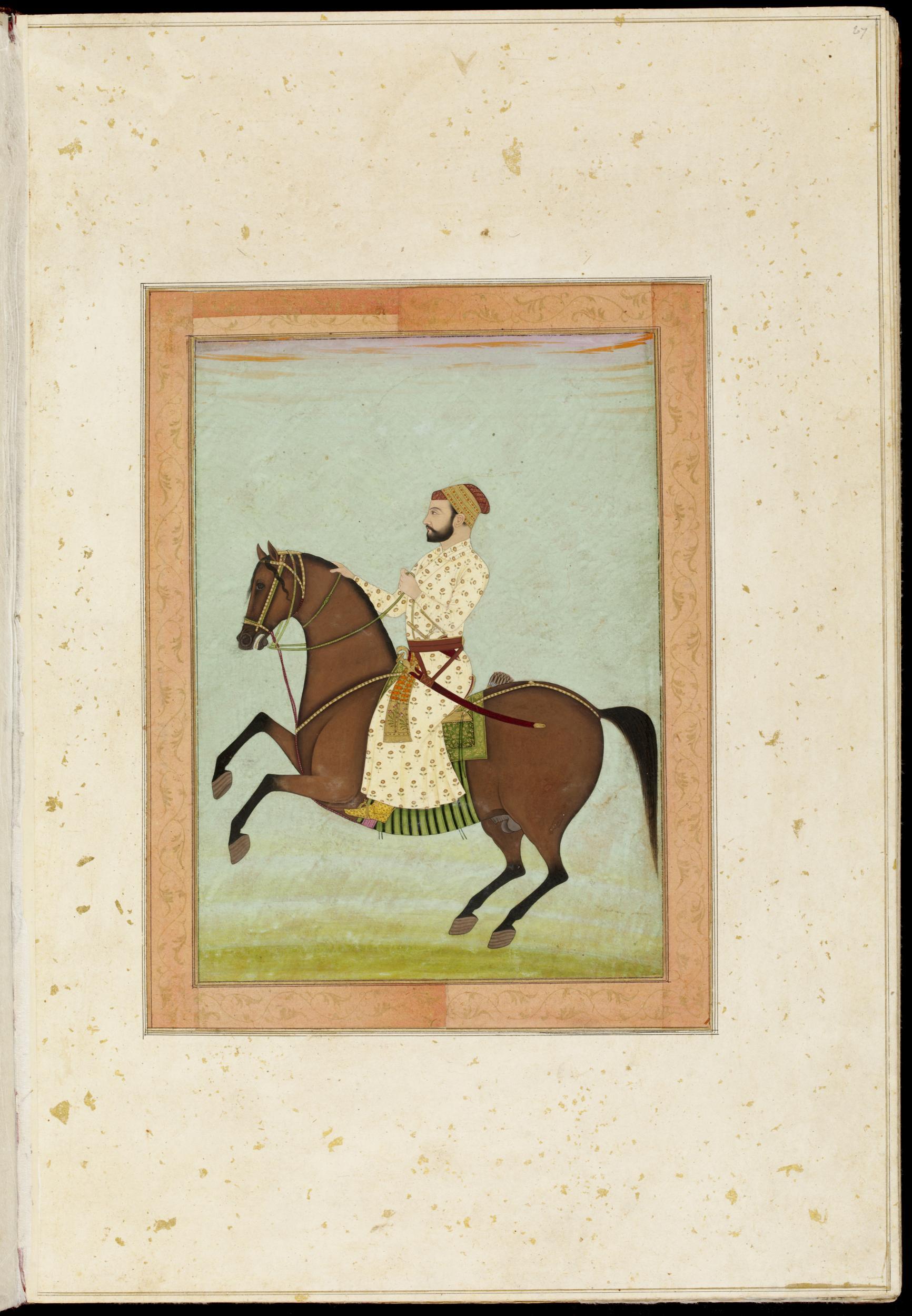

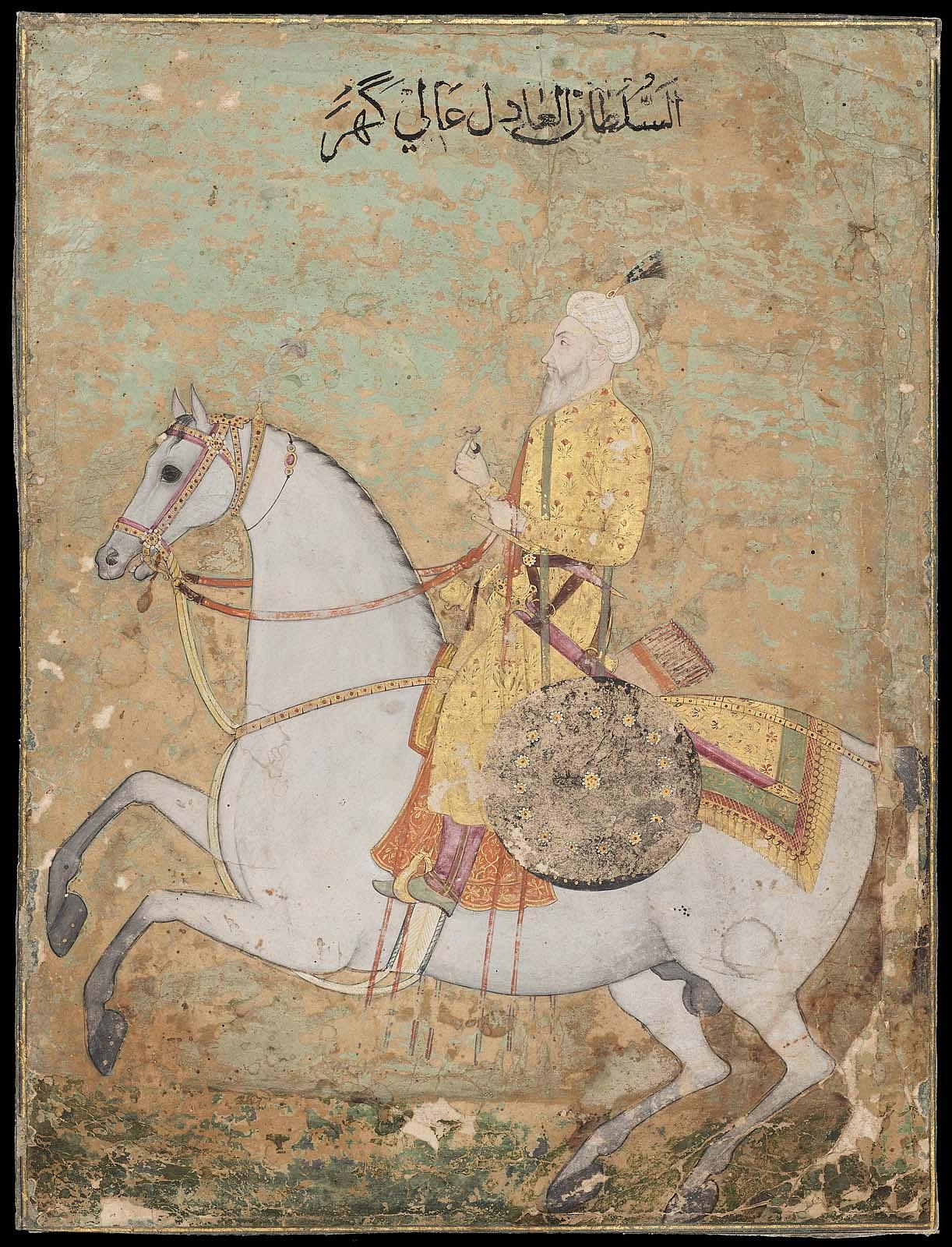

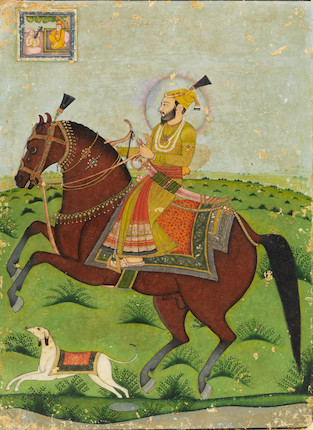

With time, Indian artists develop their own styles and iconographies. A new format, single works designed to be kept in albums (muraqqa), has emerged. Mughal painting was taking a much greater interest in realistic portraiture than typical Persian miniatures. This could be attributed to European influence, as we will shortly observe.

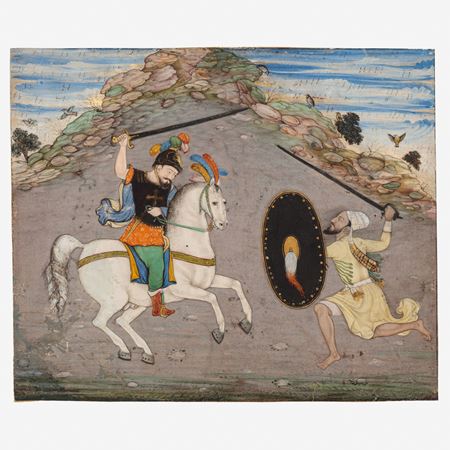

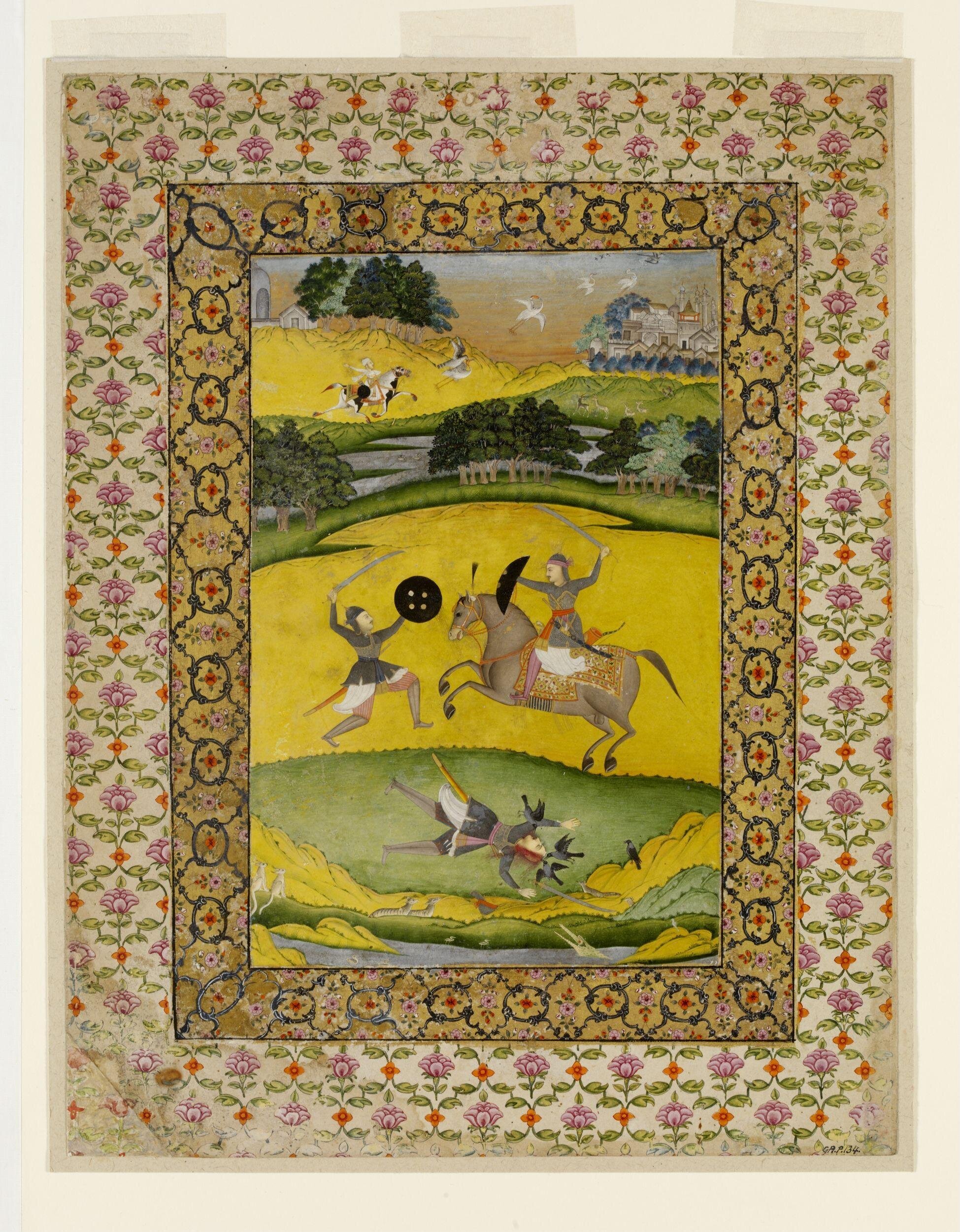

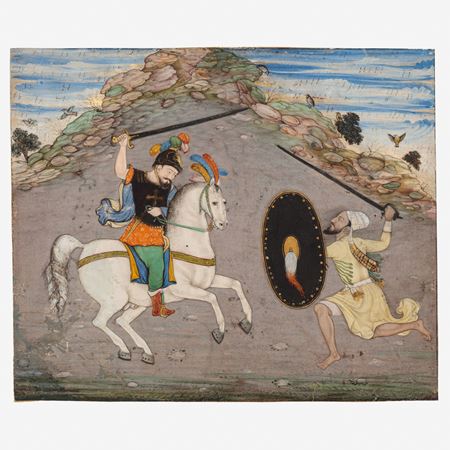

Sword fight between a Christian horseman and an Indian soldier, cr. 1600, Mughal India

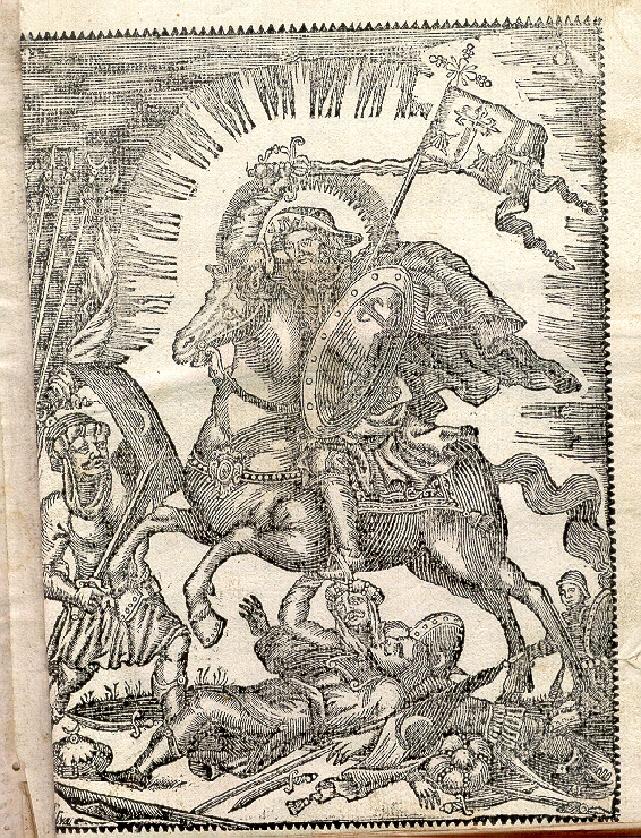

COMPARANDUM: Santiago Matamoros, 15th century, Santa María de Labrada, Guitiriz, Lugo, Spain

COMPARANDUM: Santiago Matamoros, 1747, Jacobo de la Piedra, Spain

COMPARANDUM: 'Nata Ragini' warrior on a horse fighting a foot soldier with a dead one nearby, cr. 1610, Rajasthan: Jaipur: Amber, India

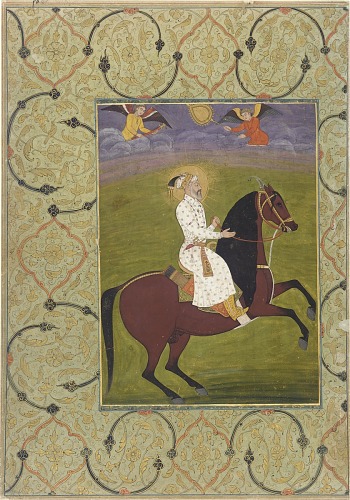

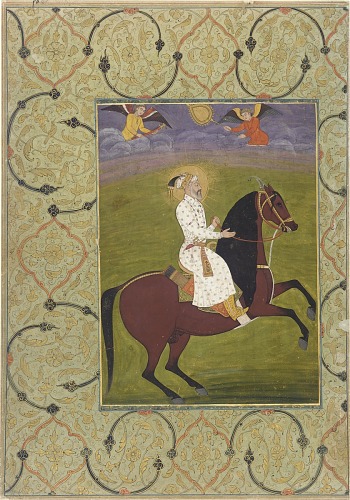

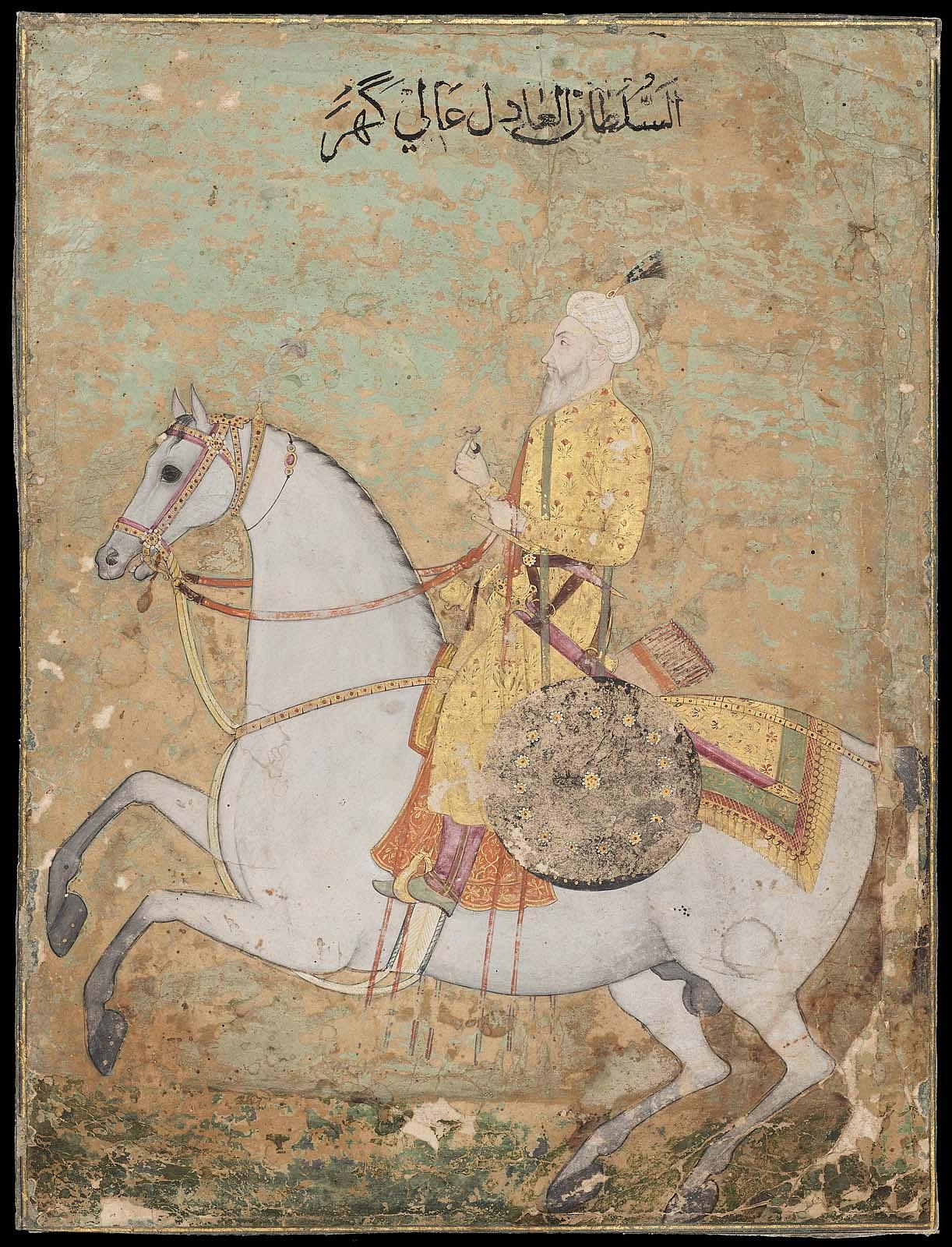

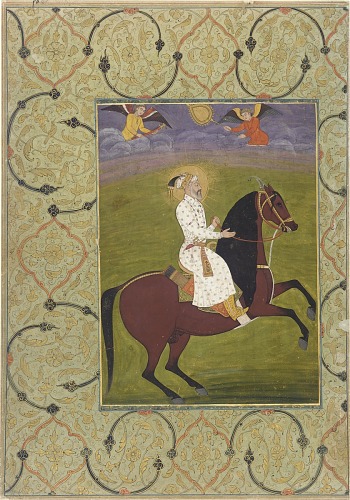

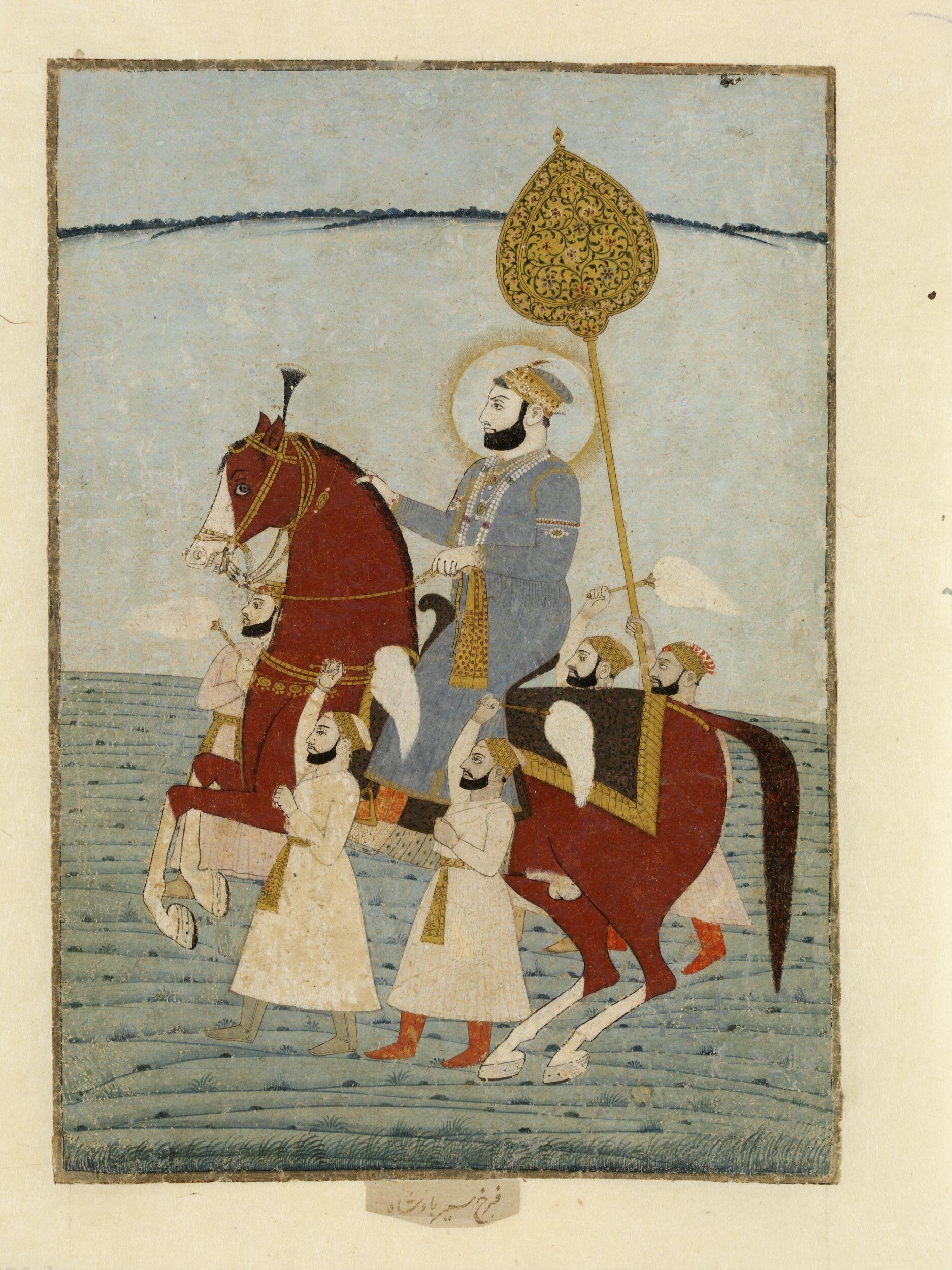

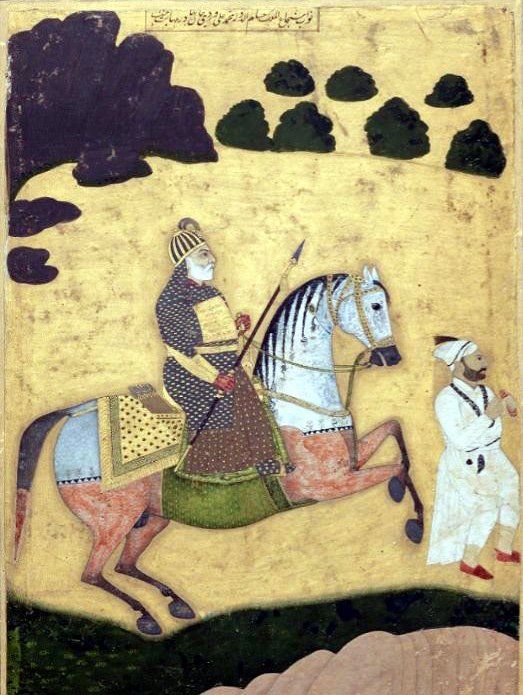

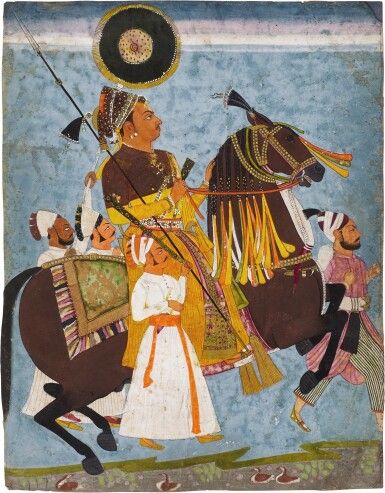

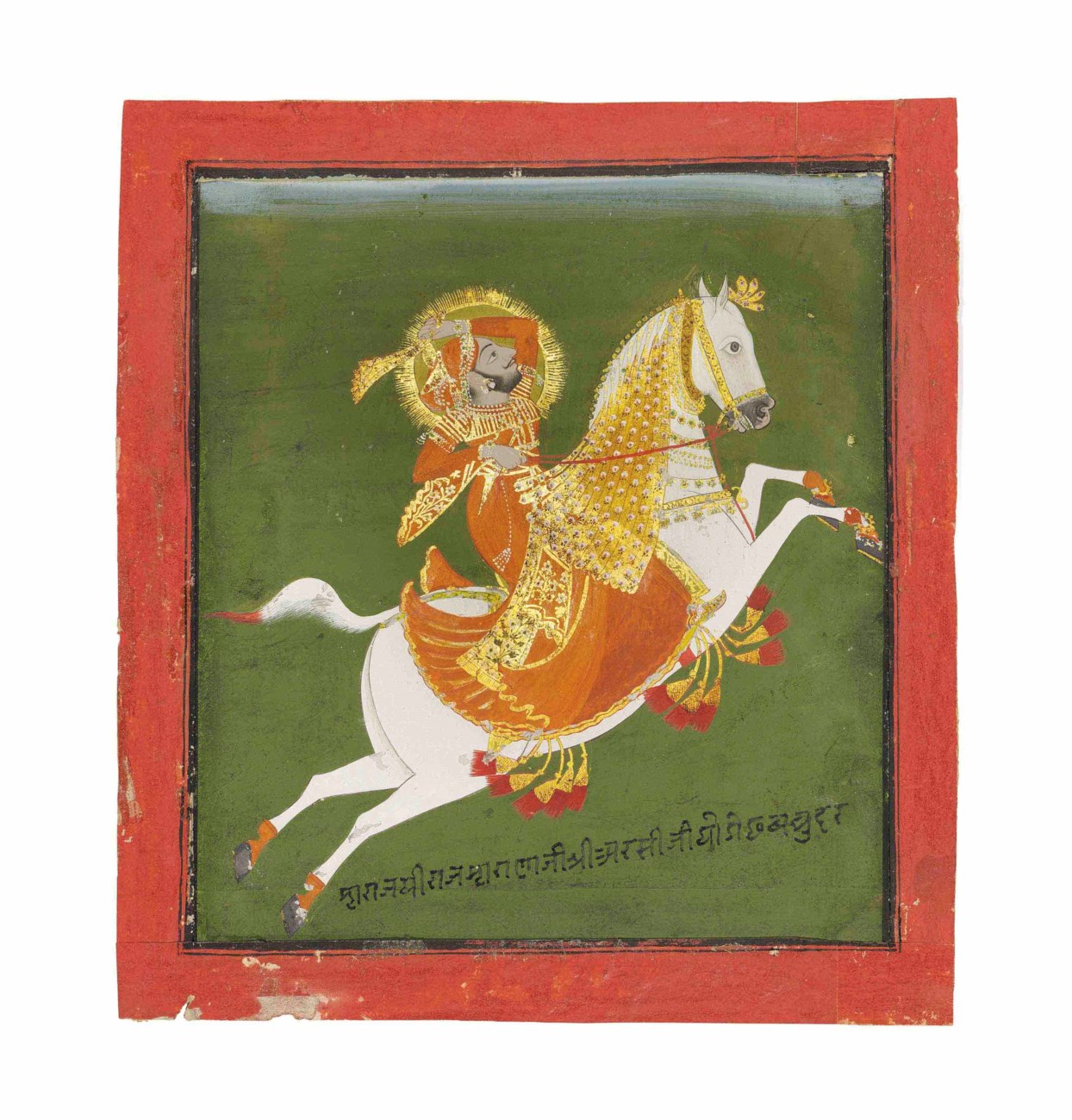

The horsemen iconography was commonly used to produce stand-alone portraits of royalty that didn’t have any narrative except the demonstation of their wealth (elaborate costumes) and status (servants). The first royal who was portrayed on a rearing horse was Muhi al-Din Muhammad, commonly known as

Aurangzeb, the sixth emperor of the Mughal Empire, ruling from July 1658 until his death in 1707. Under his emperorship, the Mughals reached their greatest extent with their territory spanning nearly the entirety of Indian subcontinent.

Anglo-Mughal War (1686–1690), ther first Anglo-Indian War on the Indian subcontinent, was fought during his reign. One could imagine that the format of the royal portrait on a rearing horse was a European import. The story told by

Amir Mohtashemi Ltd. confirms that

Jesuit priests have advertised European religios art to Mughal emperors. They suggest that the images of

James Matamoros in particular could have influenced Mughal artists. This iconography is also very similar to Nata

Raga iconography, see below.

A Mughal nobleman (Shah Jahan) on horseback, after a Mughal miniature, cr. 1656-61, Rembrandt, the Dutch Republic

COMPARANDUM: Equestrian portrait of Shahjahan (r. 1628-58), 1750-1770, Rajasthan state, India

It must be mentioned that the interest was mutual: in 1650s, at the peak of his career,

Rembrandt van Rijn drew a series of Mughal miniature – reproductions. Twenty-three

Rembrandt's Mughal drawings are scattered around different museums of the world and are known to be among the artist’s most compelling works on paper. One of them features a horseman on a rearing horse! It is presumed to portray Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb’s father. Unfortunely, I could not find any stand-alone equestrian portrait of Shah Jahan made prior to Rembrandt’s drawing. It’s possible that Rembrandt has copied a part of a more complex composition.

Equestrian portrait of emperor Aurangzeb (the preparatory study), cr. 1660, Kishangarh, India

Equestrian Aurangzeb, ca. 1650, India

Equestrian portrait of Aurangzeb, cr. 1680, ?, India

Equestrian Portrait of Bahadur Shah as a Young Man, c. 1690, attributed to Hunhar I, Mughal, India

Equestrian portrait of Shahjahan (r. 1628-58), 1750-1770, Rajasthan state, India

Prince on Horseback, 18th century, Mughal, India

Emperor Farrukhsiyar, cr. 1770-80, Murshidabad, India

Mughal noble on horseback, cr. 1790, Mughal Empire

An equestrian portrait of emperor Shah Jahan, early 19th century, India

Equestrian Portrait of Shah Alam II, 18th century, late Mughal period, India

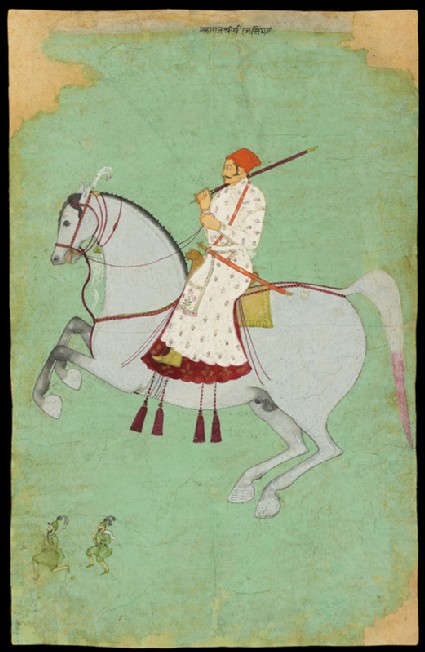

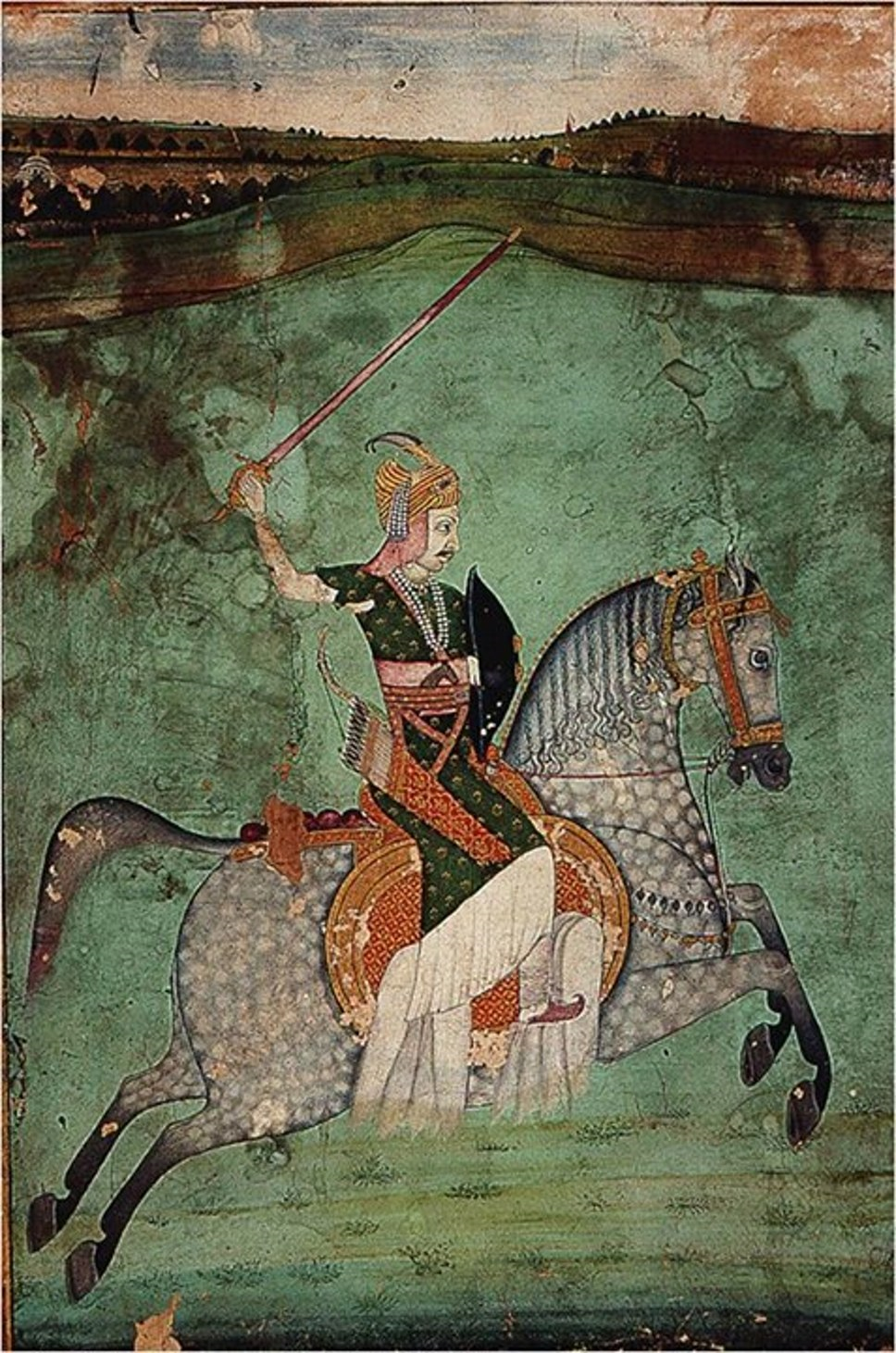

… Adopted By Other Indian Kingdoms

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

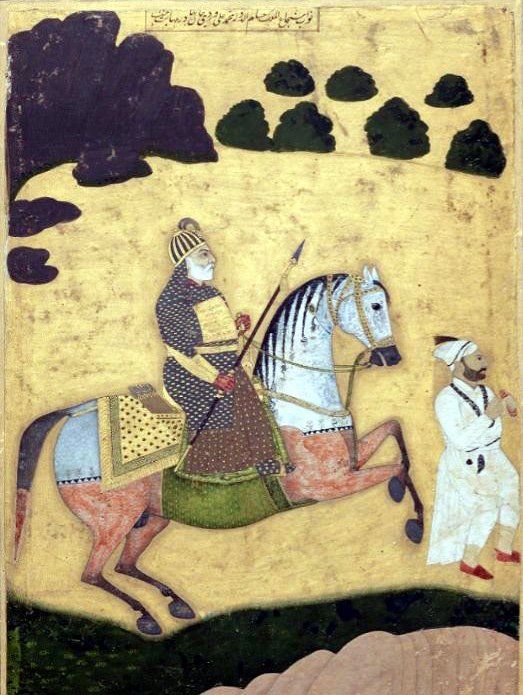

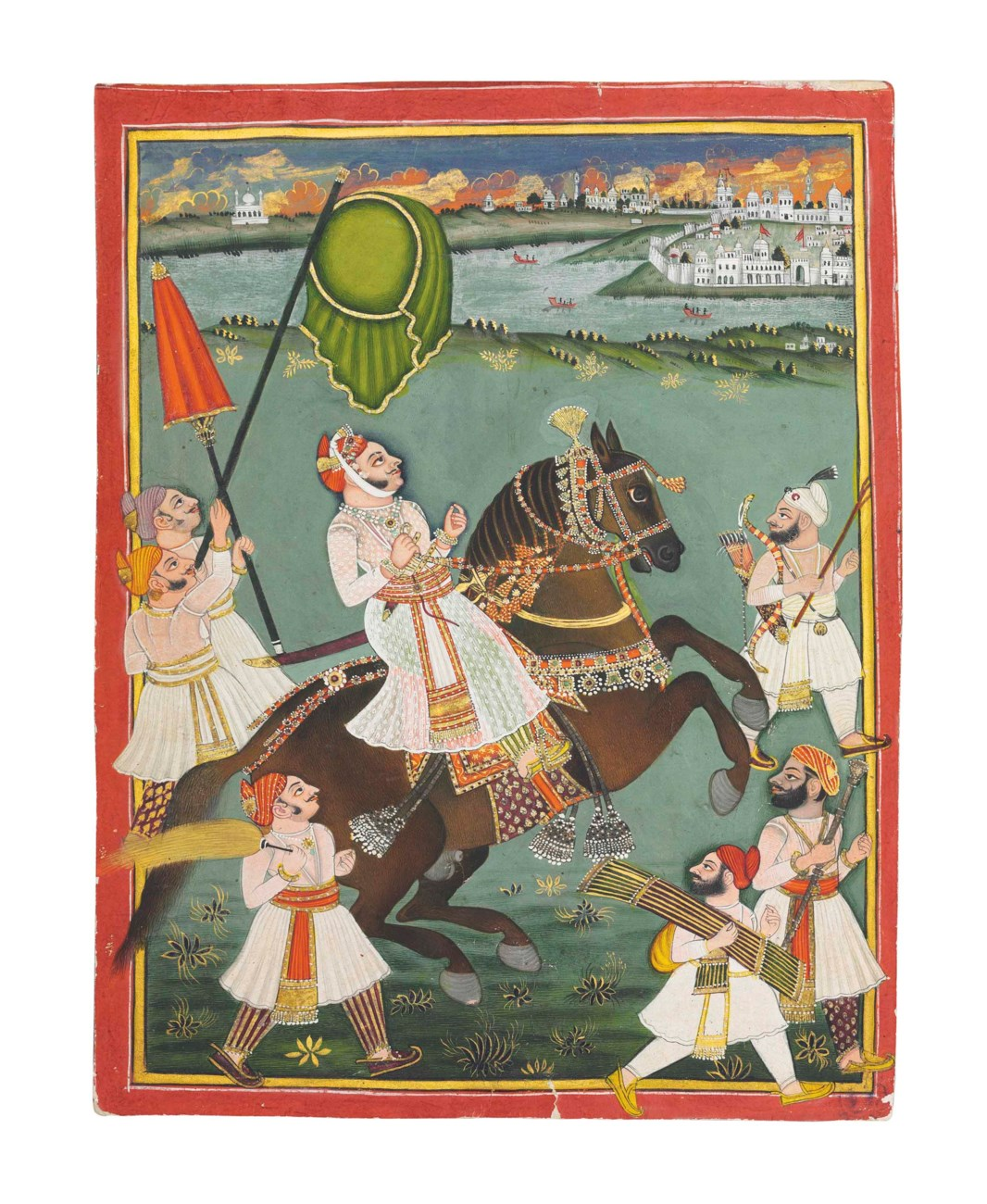

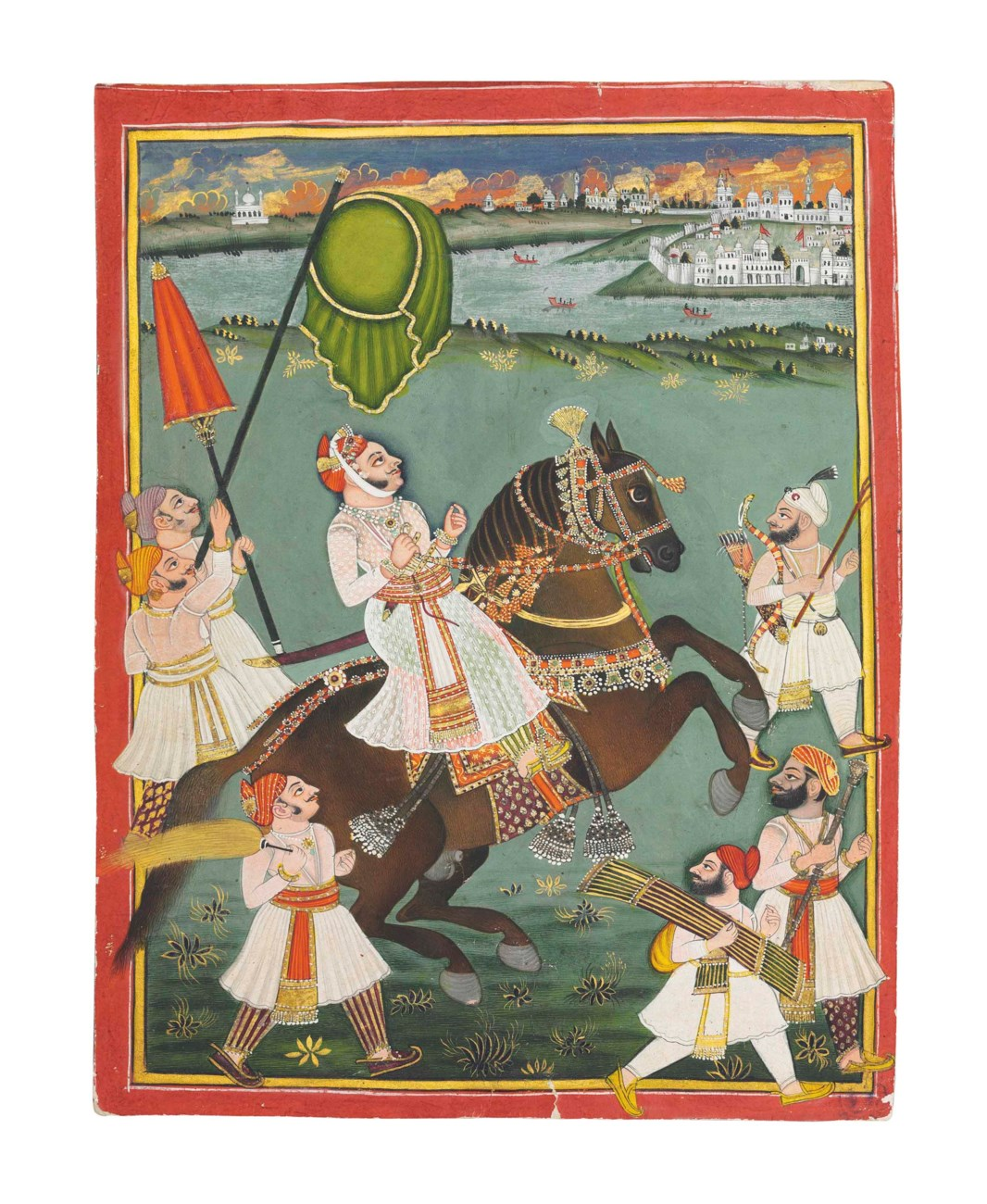

While other kingdoms of Indian subcontinent had different religions, and were often at war with Mughal empire, they have enthusiastically adopted the format of the equestrian portrait.

COMPARANDUM: Equestrian Portrait of Bahadur Shah as a Young Man, c. 1690, attributed to Hunhar I, Mughal, India

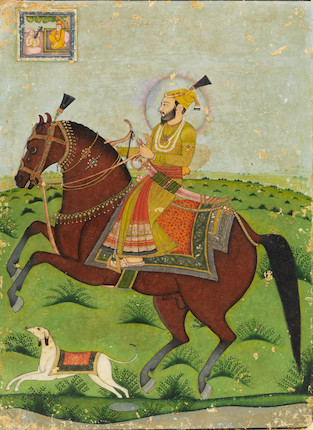

Maharana Amar Singh II Riding a Jodhpur Horse, cr. 1700-10, Rajasthan, Udaipur, India

COMPARANDUM: Equestrian portrait of Alivardi Khan, 2nd quarter 18th century, ?, India

Maharana Sangram Singh Riding a Prize Stallion, cr. 1712, Rajasthan, Mewar, India

Prince on Horseback, 18th century, Mughal, India

Maharaja Dhiraj Singh riding, cr. 1700, Raghugarh, India

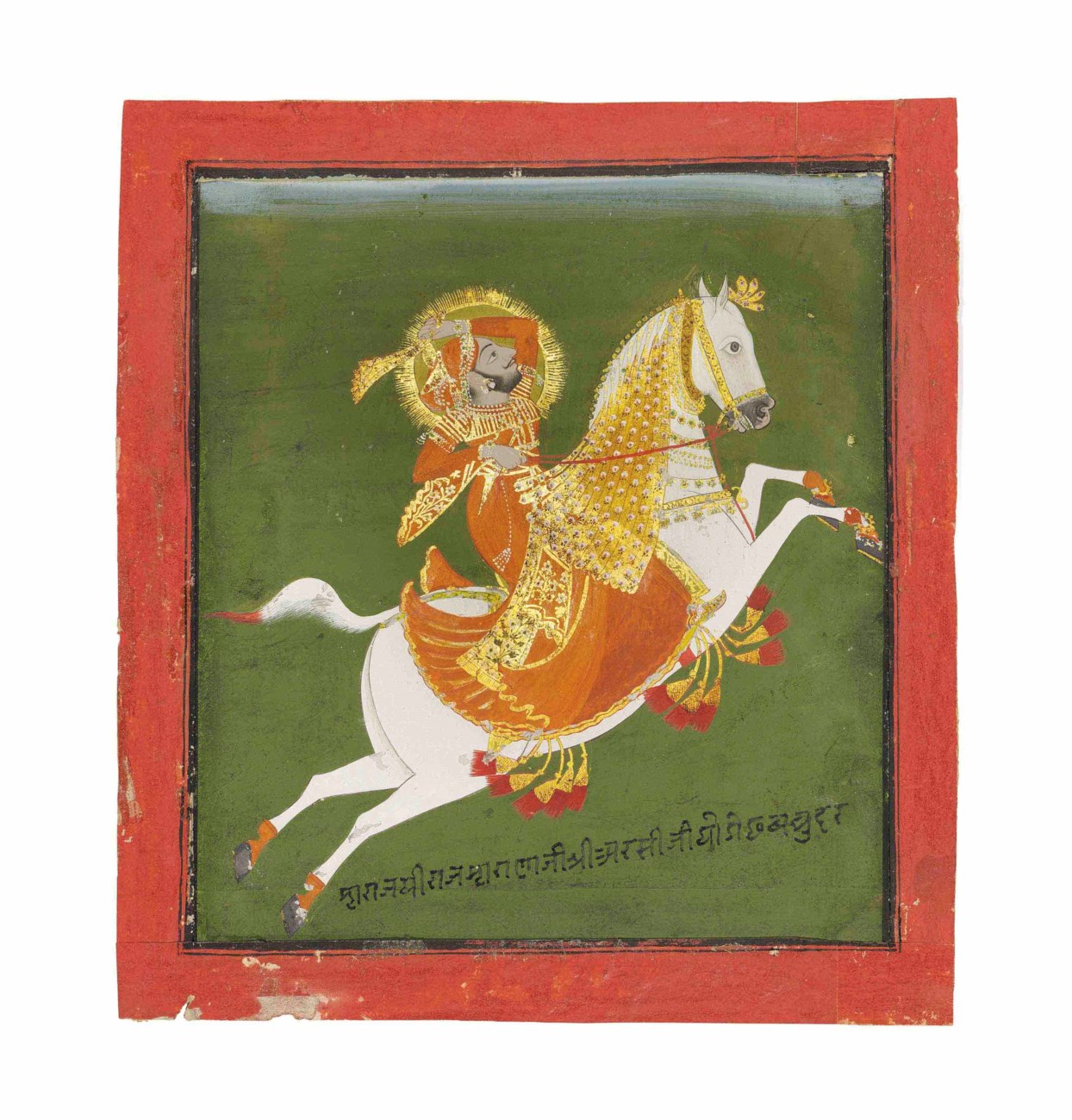

Equestrian miniature painting of Pir Budhan Shah, 18th century or 19th century, ?, India

This format was used not only for the rulers, but also for the government officials and religious leaders. Perhaps the most notable of them is the portrait of

Ikhlas Khan, a descendant of slaves from

Abyssinia who became the prime minister, and de-factor regent, of the Sultanate of Bijapur, one of

Deccan sultanates, in 17th century. This must be one of the first ones, if not the first one, stately portrait of a black person, and a slave descendant, on a rearing horse.

Maharana Raj Raj Singh I, Maharana of Mewar (ruled 1652 - 1680), riding, cr. 1670, probably Udaipur, Mewar, North India

Equestrian portrait of Maharana Raj Singh I of Mewar, 1670, Udaipur, India

Ikhlas Khan on horseback, 1670-80, Golconda, India

Baji Rao I, Peshwa of the Maratha Empire, cr. 1720-40, Maratha Empire, present-day India

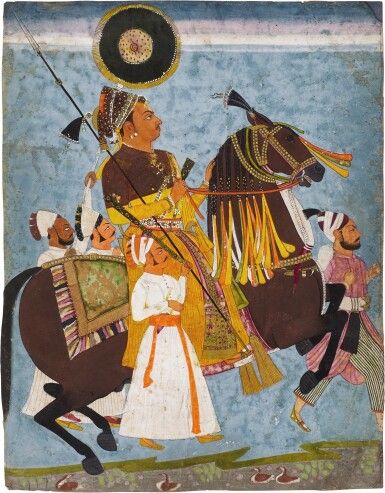

Maharaja Abhai Singh of Jodhpur (r.1724-49) on horseback with attendants, 1724-49, Marwar, Rajasthan, India

Maharana Ari Singh of Mewar (r. 1762-72) riding with a companion, cr. 1765-66, Jugarsi, Mewar, Rajasthan

An equestrian portrait of Maharana Ari Singh, cr. 1768-69, Jugarsi, Udaipur, Mewar, Rajasthan, North-West India

An equestrian portrait of Mādhav Rāo, cr. 1775, Maharashtra, India

A Jodhpur nobleman on horseback with a group of lancers, circa 1810-20, Jodhpur, India

Hira Singh and Ranjit Singh, cr. 1820, India

A large equestrian portrait of a maharaja Jawan Singh of Mewar, cr. 1830, Udaipur, India

COMPARANDUM: King John hunting, 14th century, England

Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh Guru, on horseback, circa 1830, Punjab Plains, India

Equestrian portrait of Madan Singh of Jala, cr. 1835, Bundi, Rajasthan, North India

An equestrian portrait of Narinder Singh, maharaja of Patiala, mid-19th century, Patiala school, India

An equestrian portrait of Maharana Sarup Singh, cr. 1860, Attributed to Shiva Lall, Udaipur, India

Maharana Shambhu Singh throwing a javelin, 1866, Tara, Mewar, India

Maharaja Chhatrasal on horseback, circa 1865-80, Kota, India

An equestrian portrait of maharao Kishore-Singh II of Kotah, February 1865, Udaipur, India

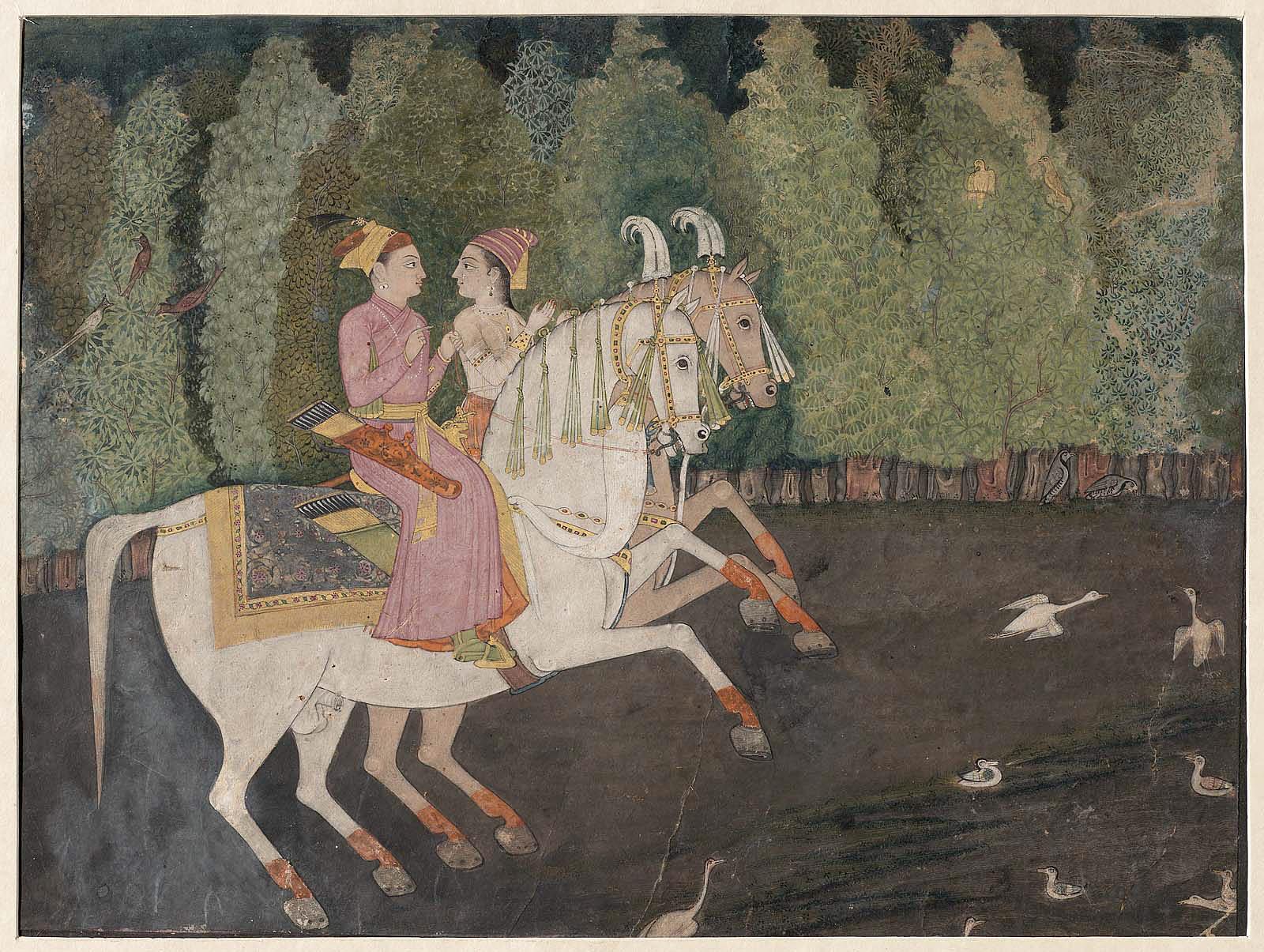

Baz Bahadur and Rupmati

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

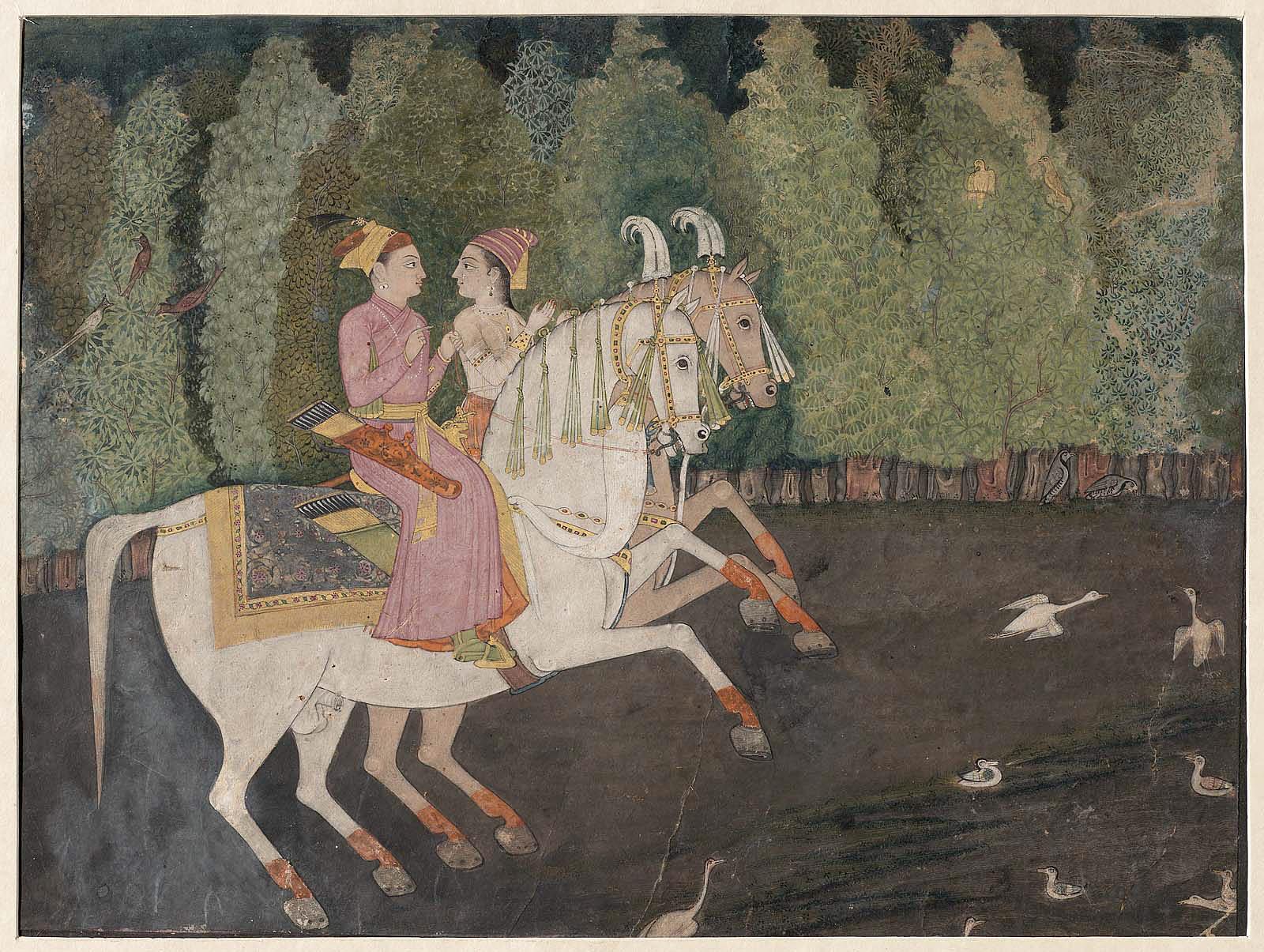

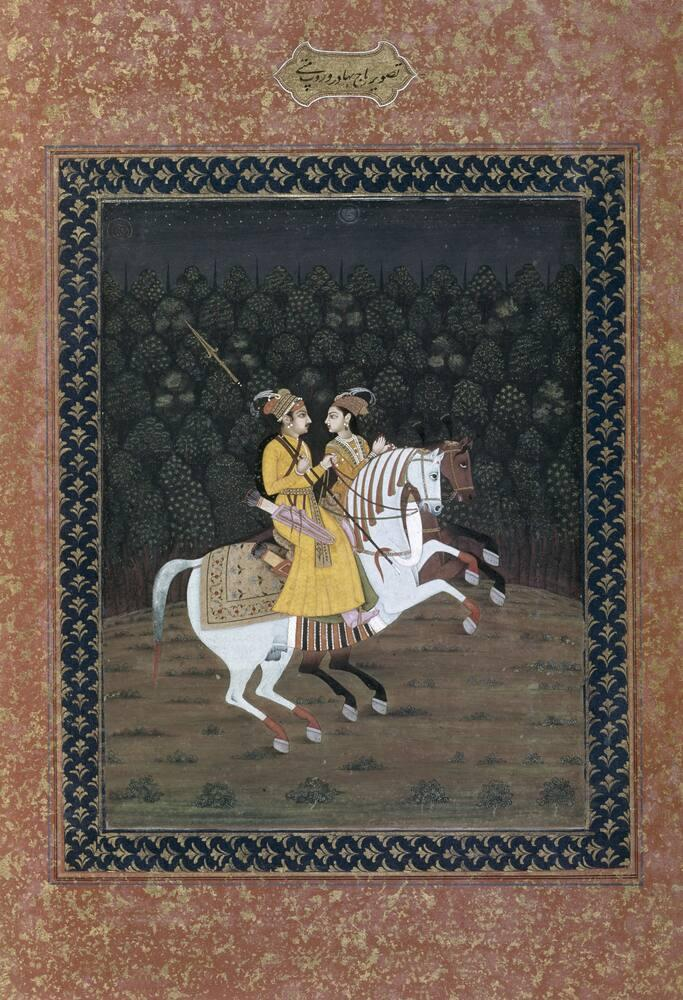

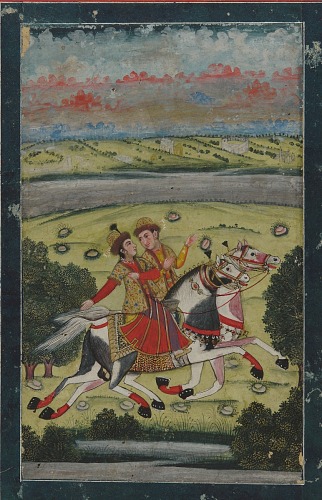

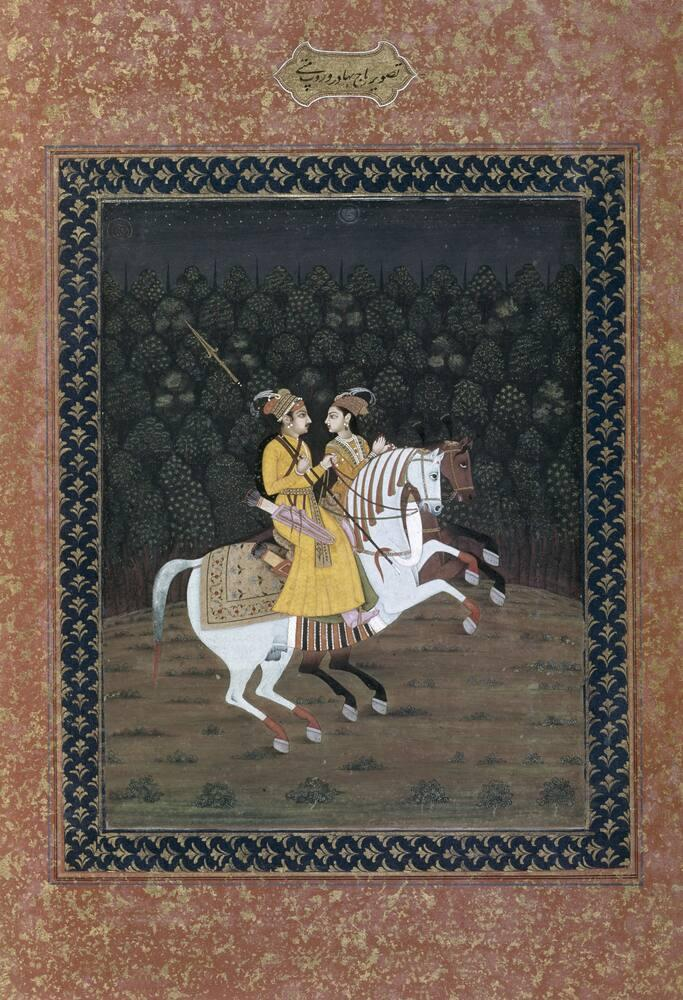

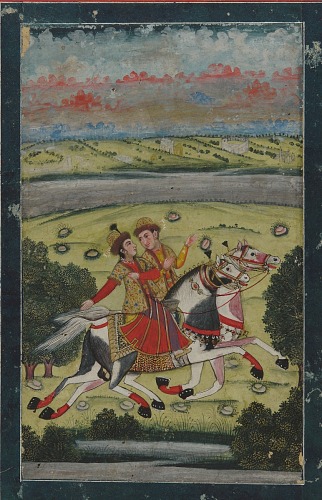

A Prince and princess on horseback, 18th century, Mughal Empire

Hunting Scene: Prince and Princess on Horseback, 18th century, Mughal Empire

Baz Bahadur Riding with Rupmati, 18th century, Malwa, India

A Noble Pair on Horseback, 19th century, India

Polo

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Ladies playing polo (Chaugen), Late 17th century, Delhi, India

Princess Playing Polo, 18th century, Dana, Jodhpur, Mughal Empire

Women playing polo, 18th century, Deccan, India

Chand Bibi playing Polo, 1700-50, Deccan, Hyderabad, India

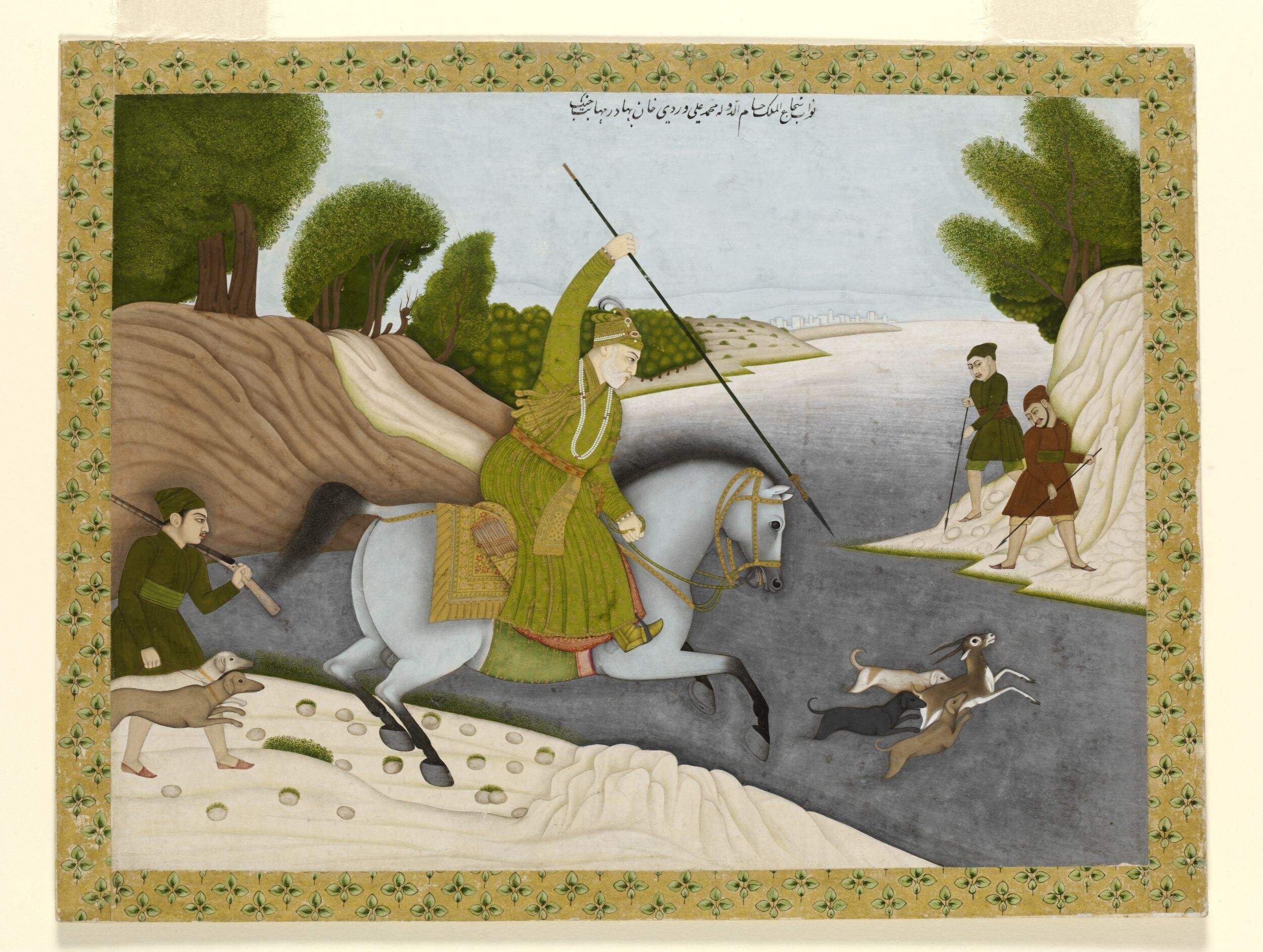

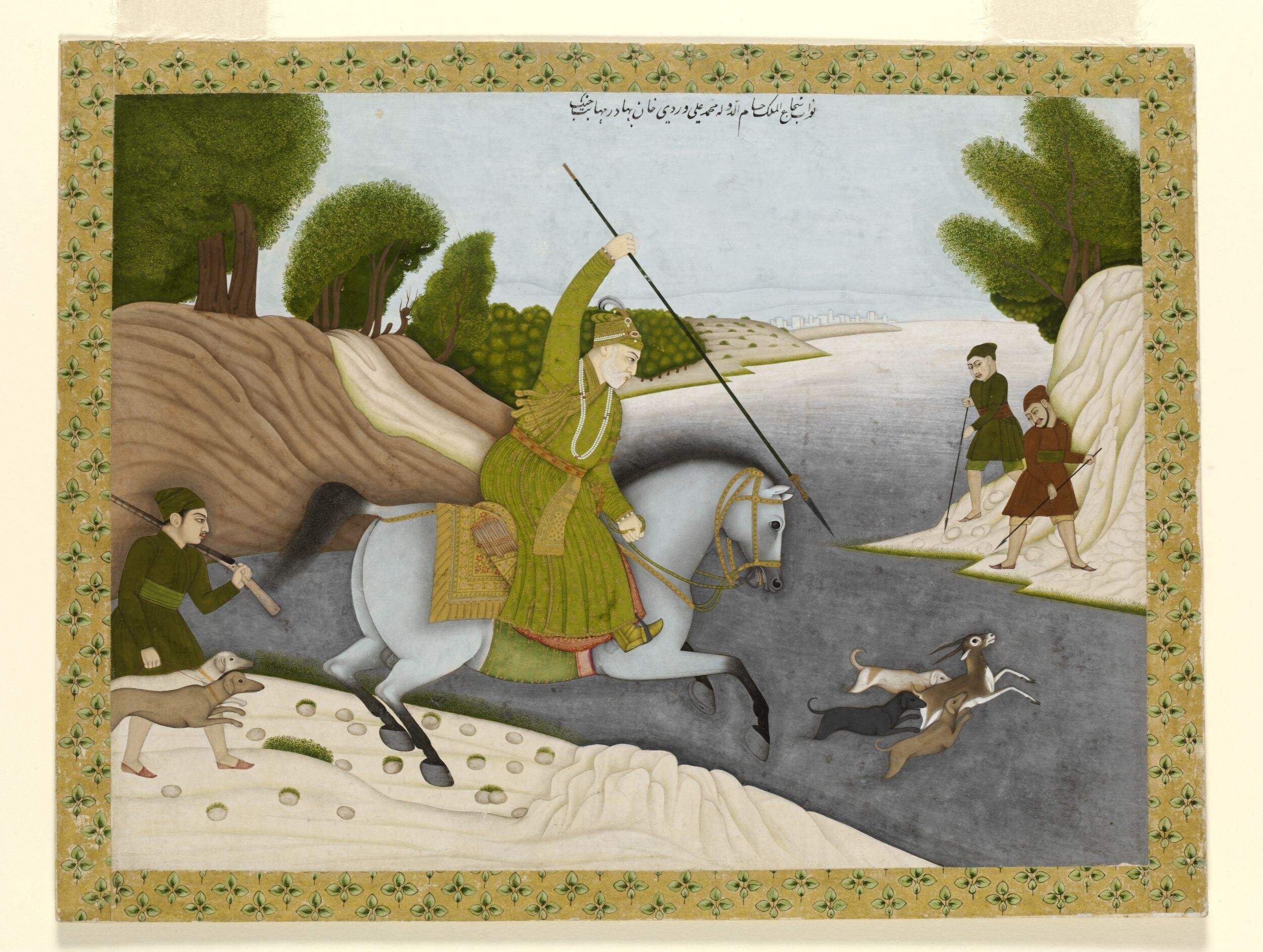

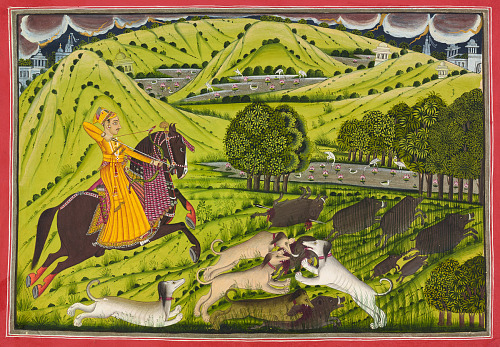

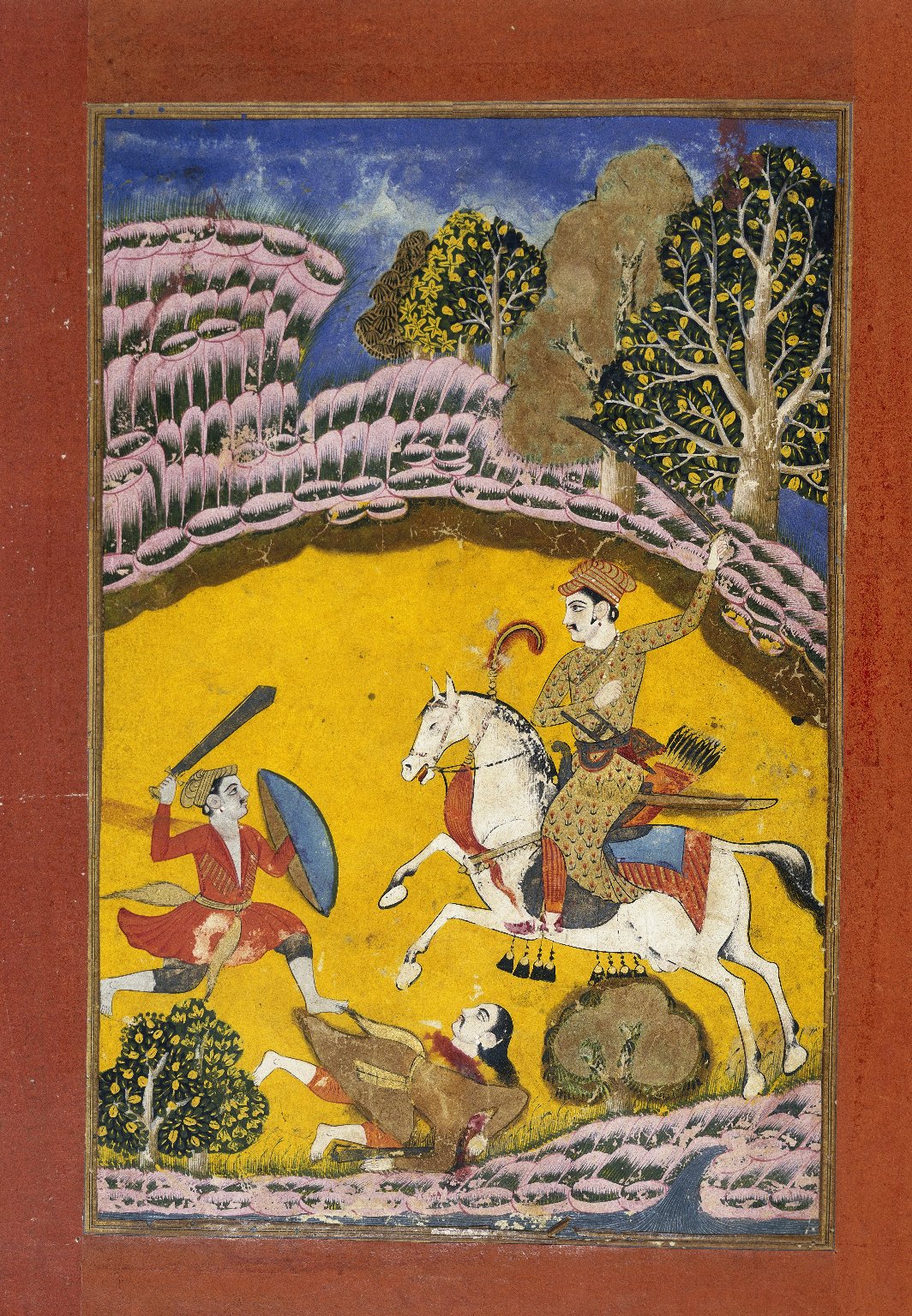

Hunting

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

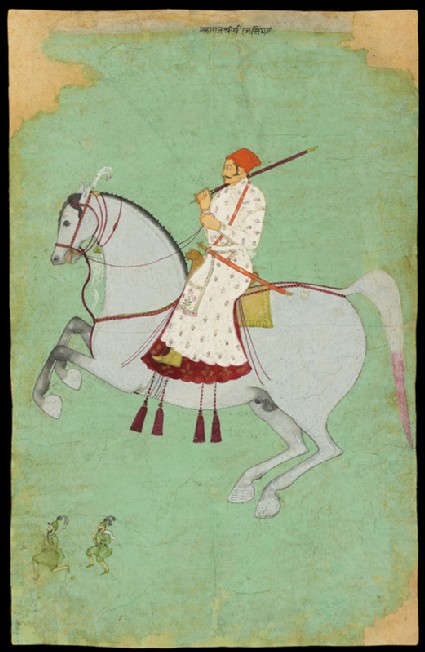

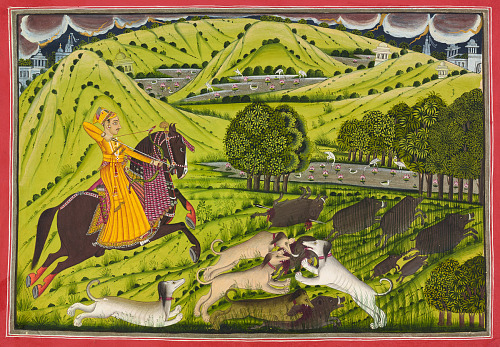

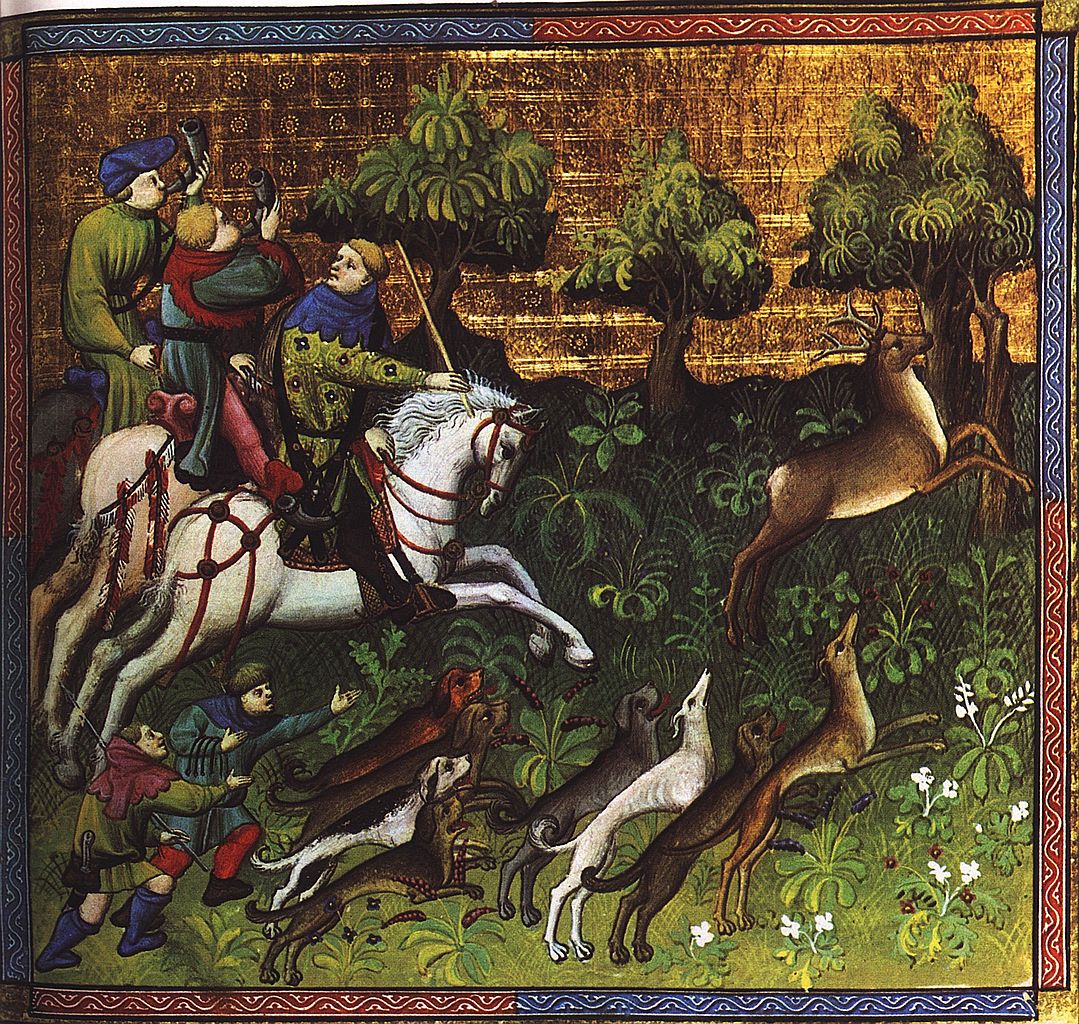

Indian rulers liked being depicted as hunters. Based on the imaged below, were usually hunting with a lance, and used dogs and/or a bird of pray, thus following a long-established tradition.

Rao Jagat Singh of Kotah hunting boar, second half of the 17th century, Kotah, Rajasthan, North India

Maharaja Diraj Singhji hunting nilgais, early 18th century, Raghugarh, Rajasthan, North India

Nawab Alivardi Khan, cr. 1750, Murshidabad, India

Two ladies on horseback hunting wild boar, cr. 1760, Rajasthan, India

Maharana Ari Singh II hunting wild boars, cr. 1760-70, Udaipur, Mewar, North India

Maharana Ari Singh (r. 1762-72) hunting boar, cr. 1763-64, ascribed to Deva, Mewar, Rajasthan, India

Ladies Hawking, late 18th century, Kashmir (Jammu and Kashmir), India

Prince Bakhtavar Singh of Jhilai in his youth, ca. 1800, Jhilai, Rajasthan state, India

Raja Madan Singh Jat, cr. 1800, Jaipur, India

Shah Jahan hunting, ca. 1900, India

COMPARANDUM: Cylinder seal with a scene of a rider in a Median dress with a spear and a dog chasing a fallow deer, 538 BC-331 BC, Achaemenid Persia

COMPARANDUM: Inlaid tile showing a hunter with a dog, 13th-15th century, Laon region, France

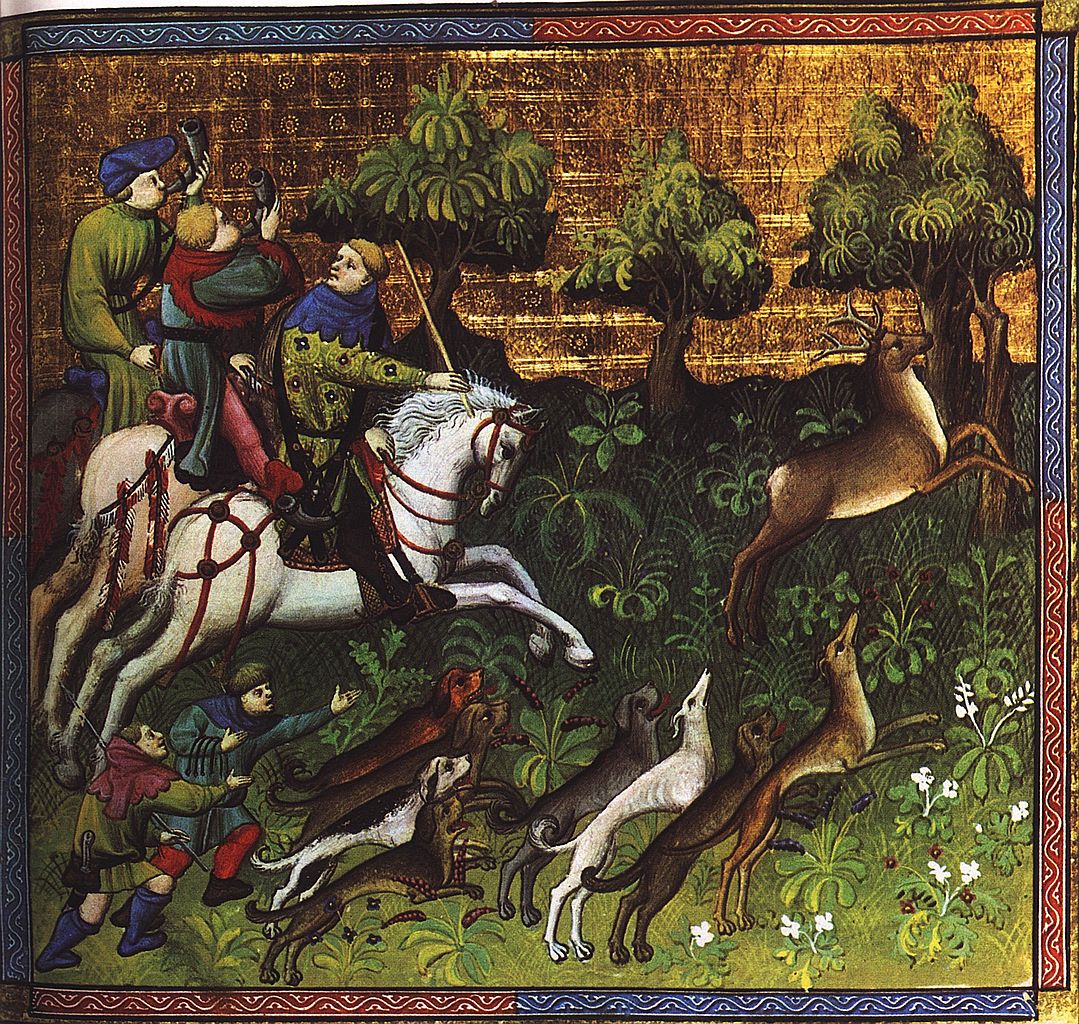

COMPARANDUM: Deer-hunting with greyhounds, illustration of The Hunting Book of Gaston Phebus, early 15th century, France

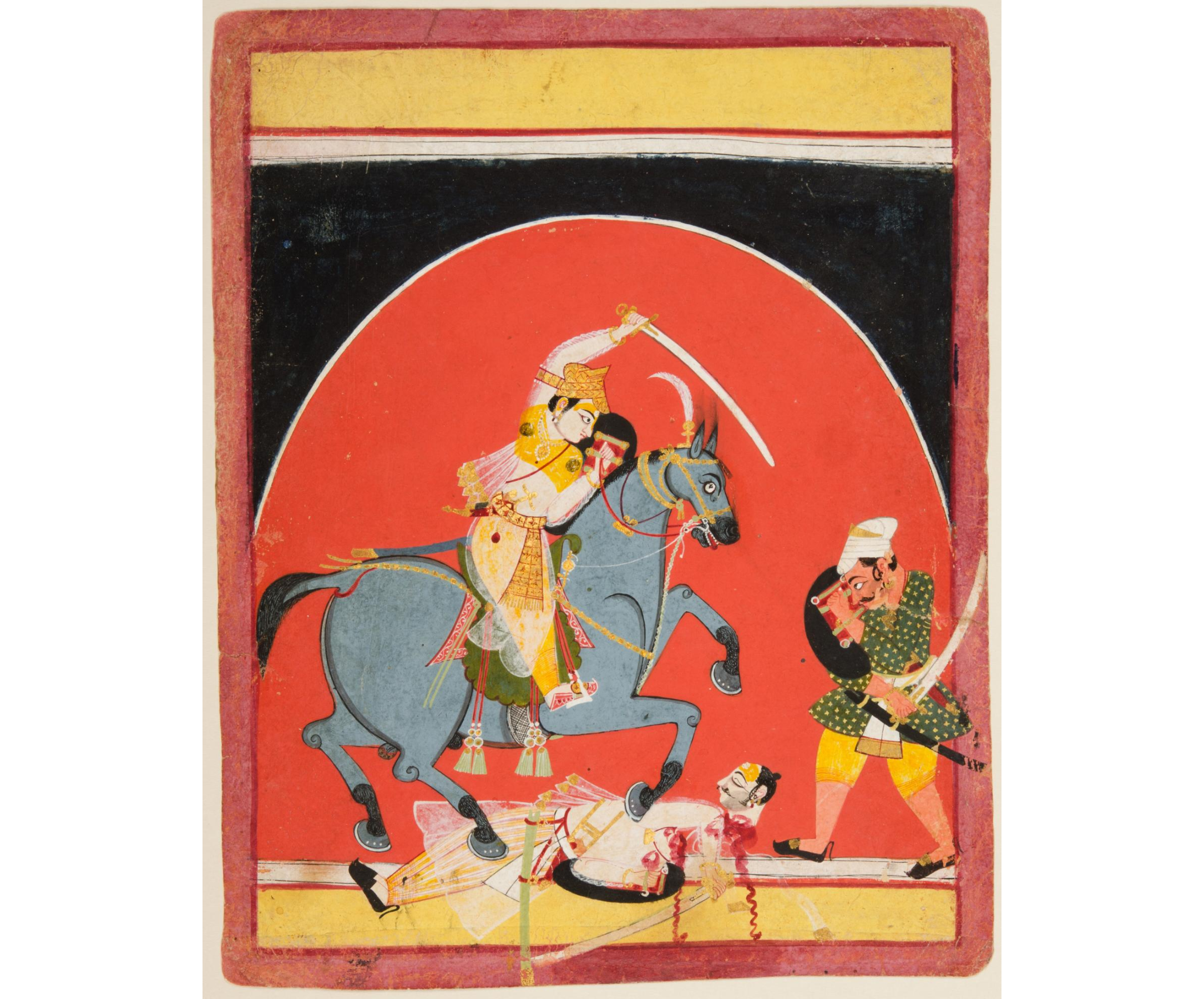

Nata Raga

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

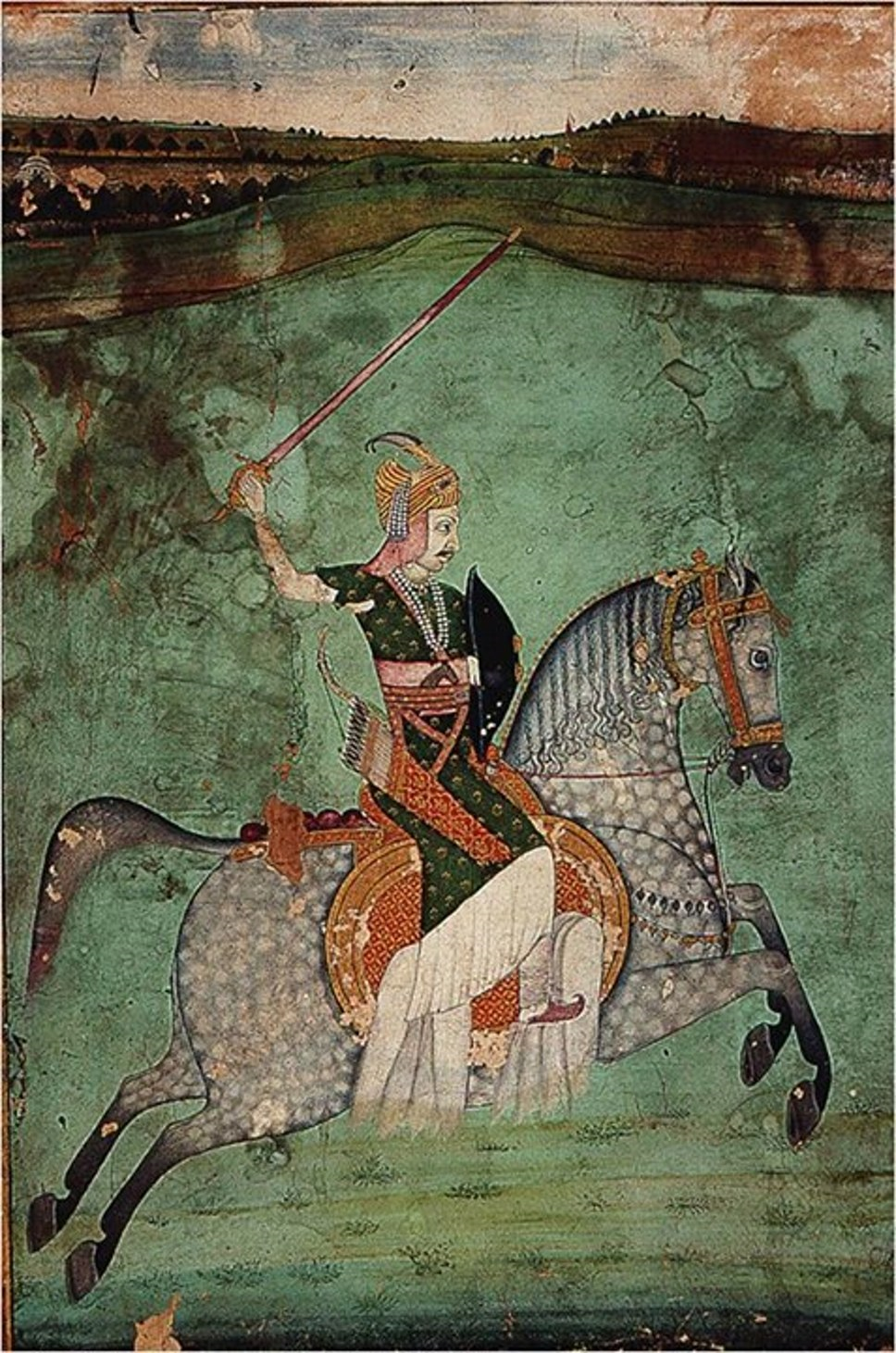

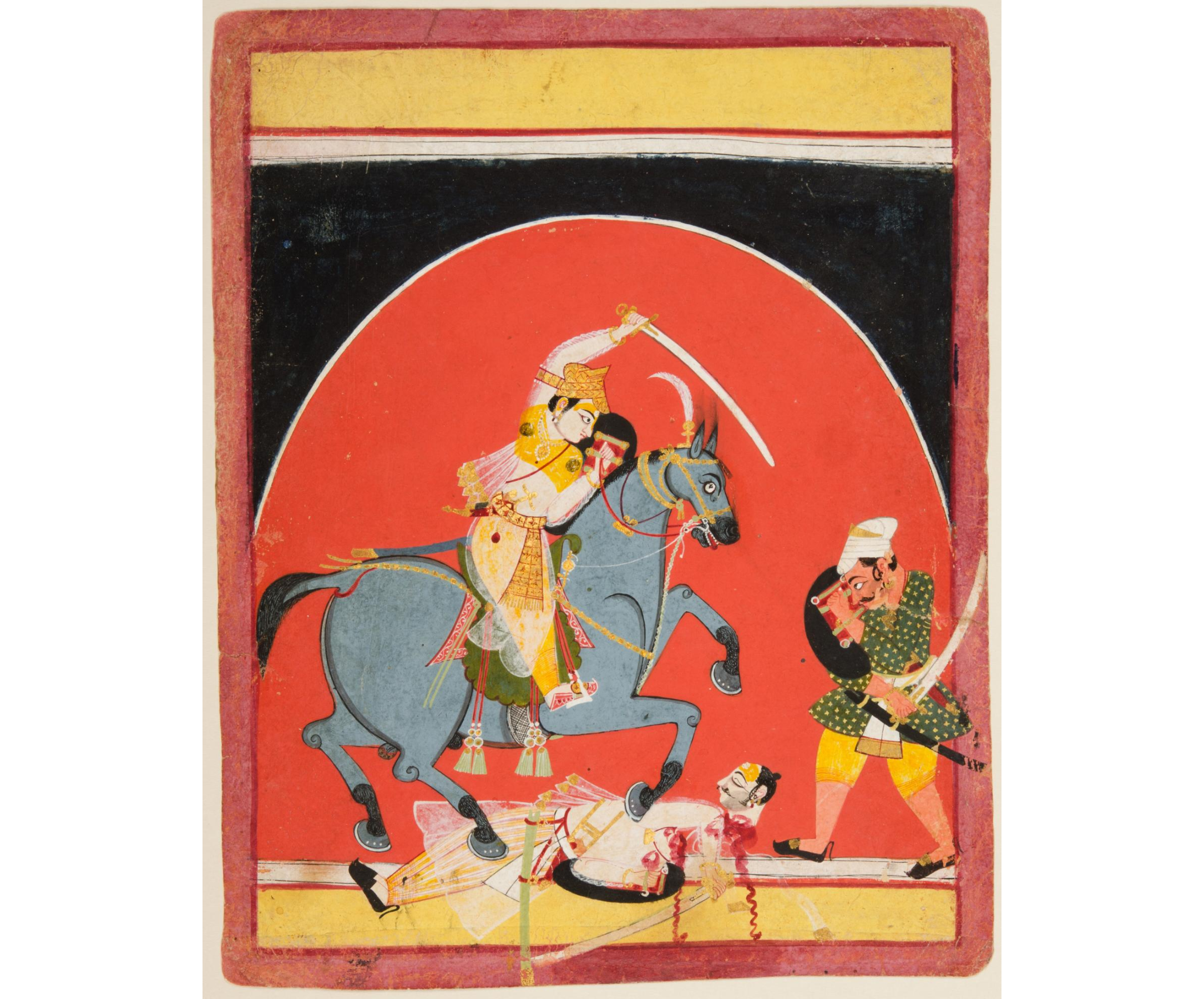

According to the Brooklyn museum research, a new genre of painting developed that attempted to capture in imagery the moods of famous passages of classical Indian music was established in the 15th or 16th century. The music, known as ragas or raginis, inspired artists to create little scenarios—happy or sad, fierce or quiet, taking place in the daytime or nighttime, the summer or winter—that were illustrated over and over again.

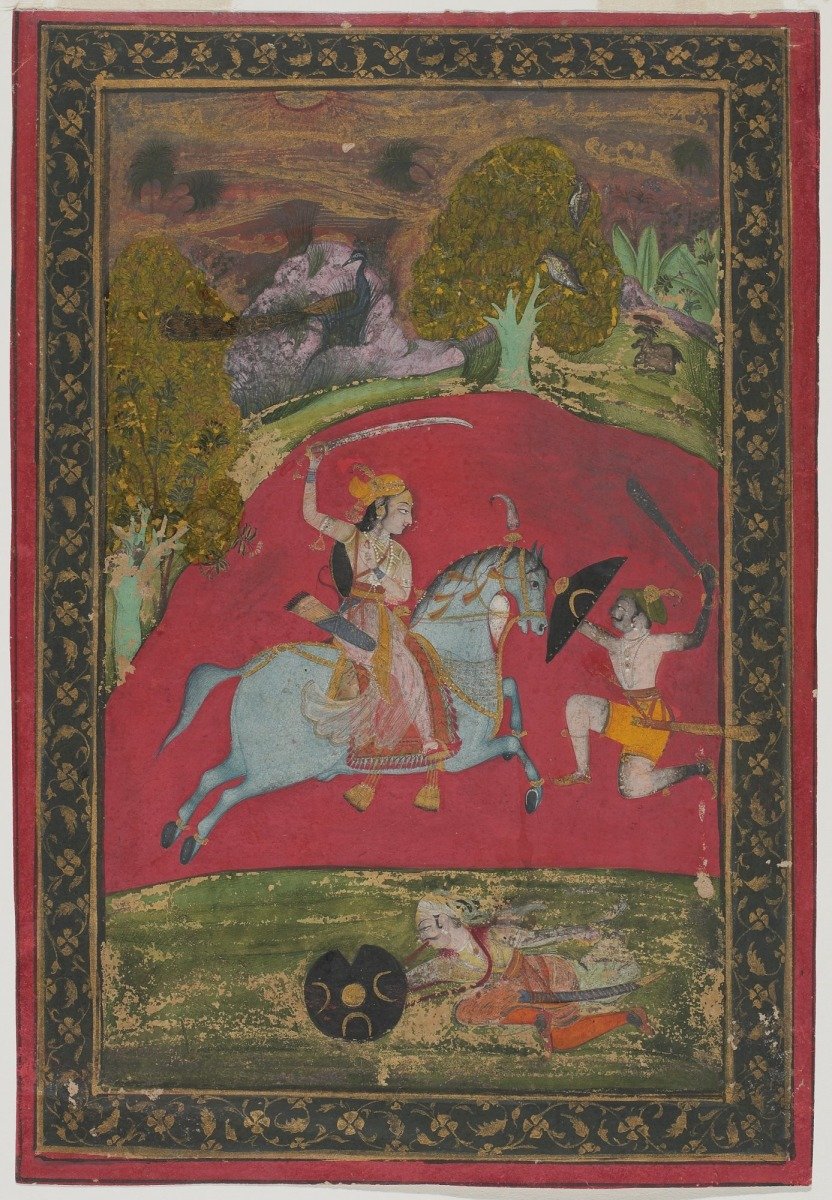

The Nata musical theme is always depicted with warriors fighting. According to the University of Michingan Museum of Art, paintings of the Nata ragini often depict a battle scene in which the heroine defeats Viraha, who personifies the separation of lovers. Lady Nata is one of the wives of Bhairava raga.

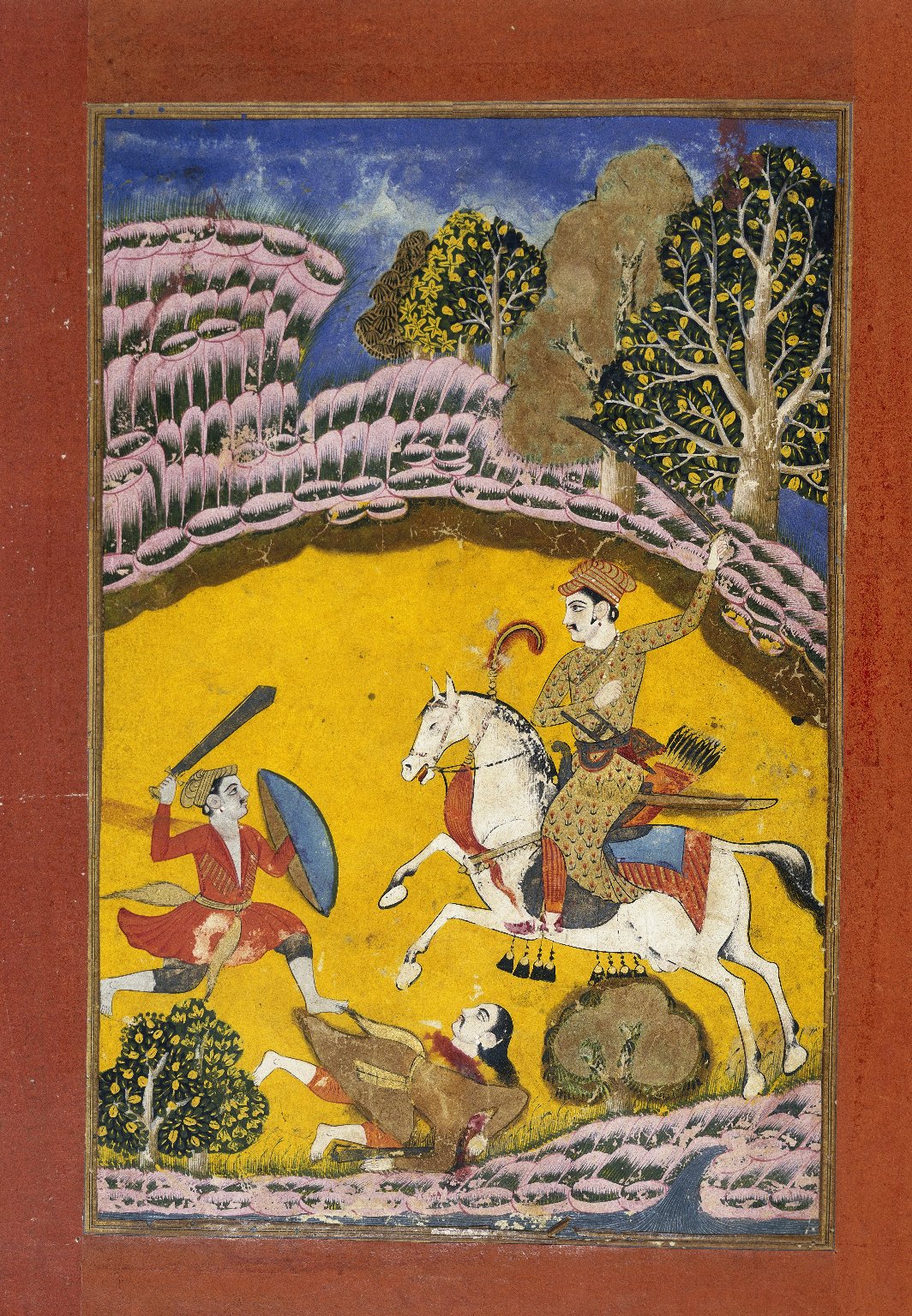

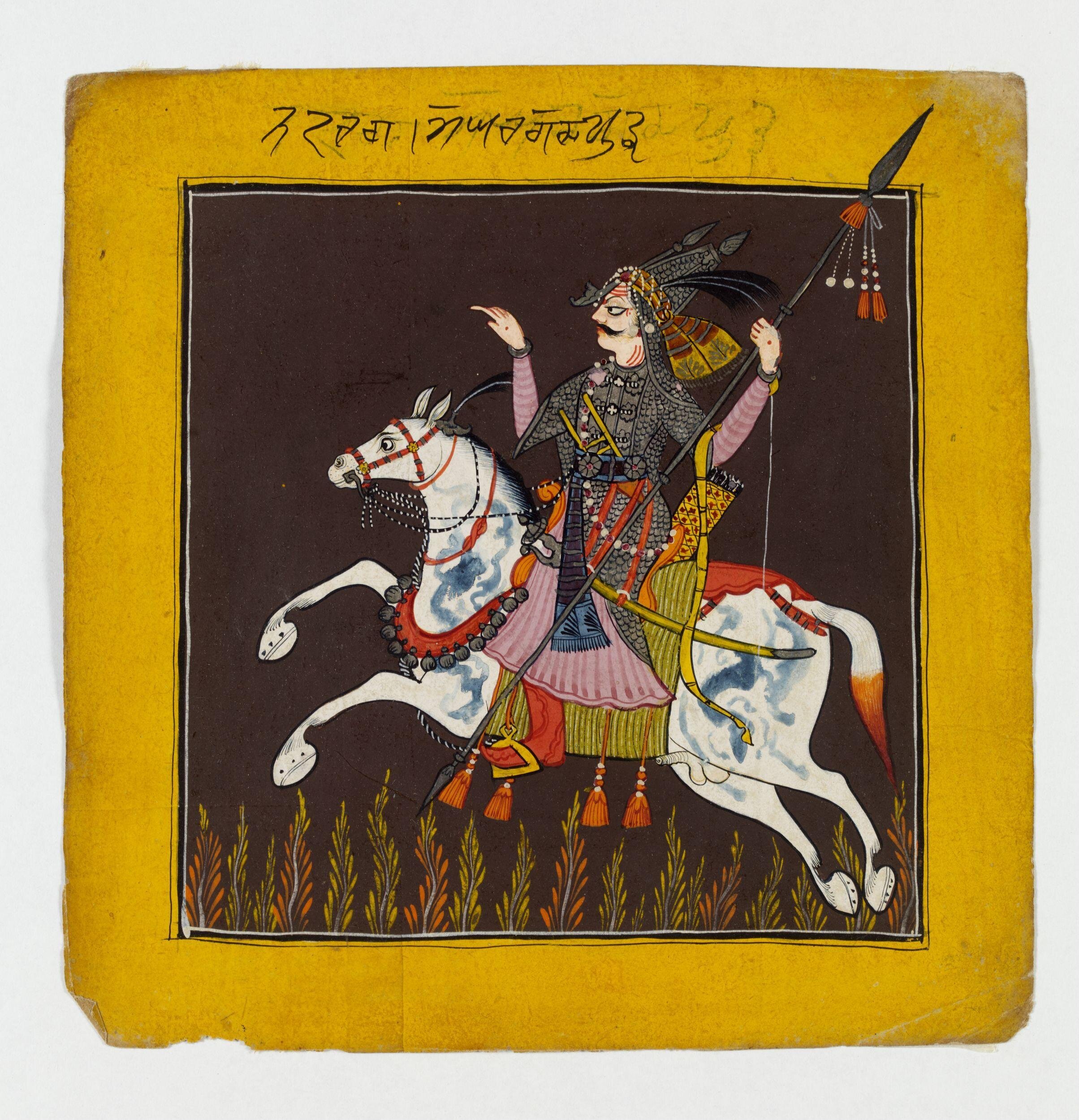

'Nata Ragini' warrior on a horse fighting a foot soldier with a dead one nearby, cr. 1610, Rajasthan: Jaipur: Amber, India

Nata Ragini (A Horseman Battles Foot Soldiers), cr. 1650-60, Madhya Pradesh, Malwa Region, India

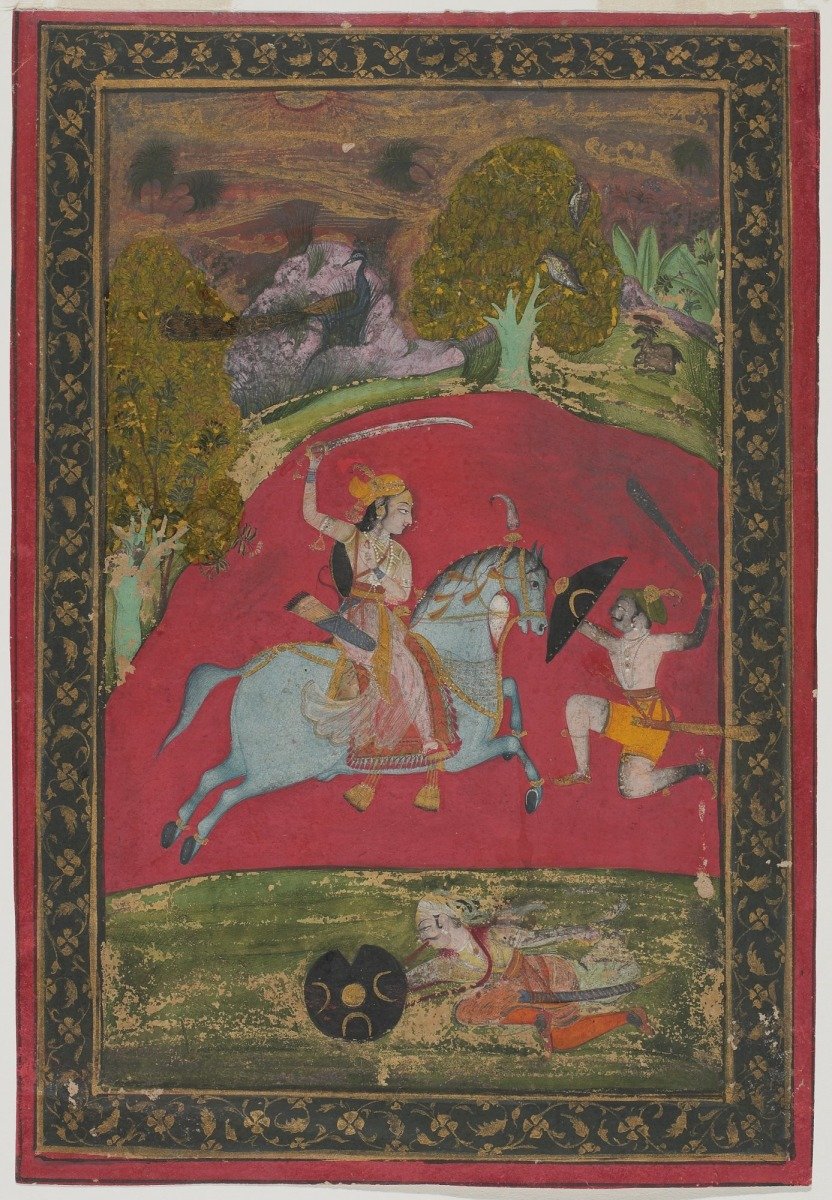

Nata Ragini, Page from a Ragamala Series, cr. 1675, Deccan or Rajasthan, India

Nata Ragini, Folio from a Ragamala, cr. 1675, Bundi, Rajasthan, India

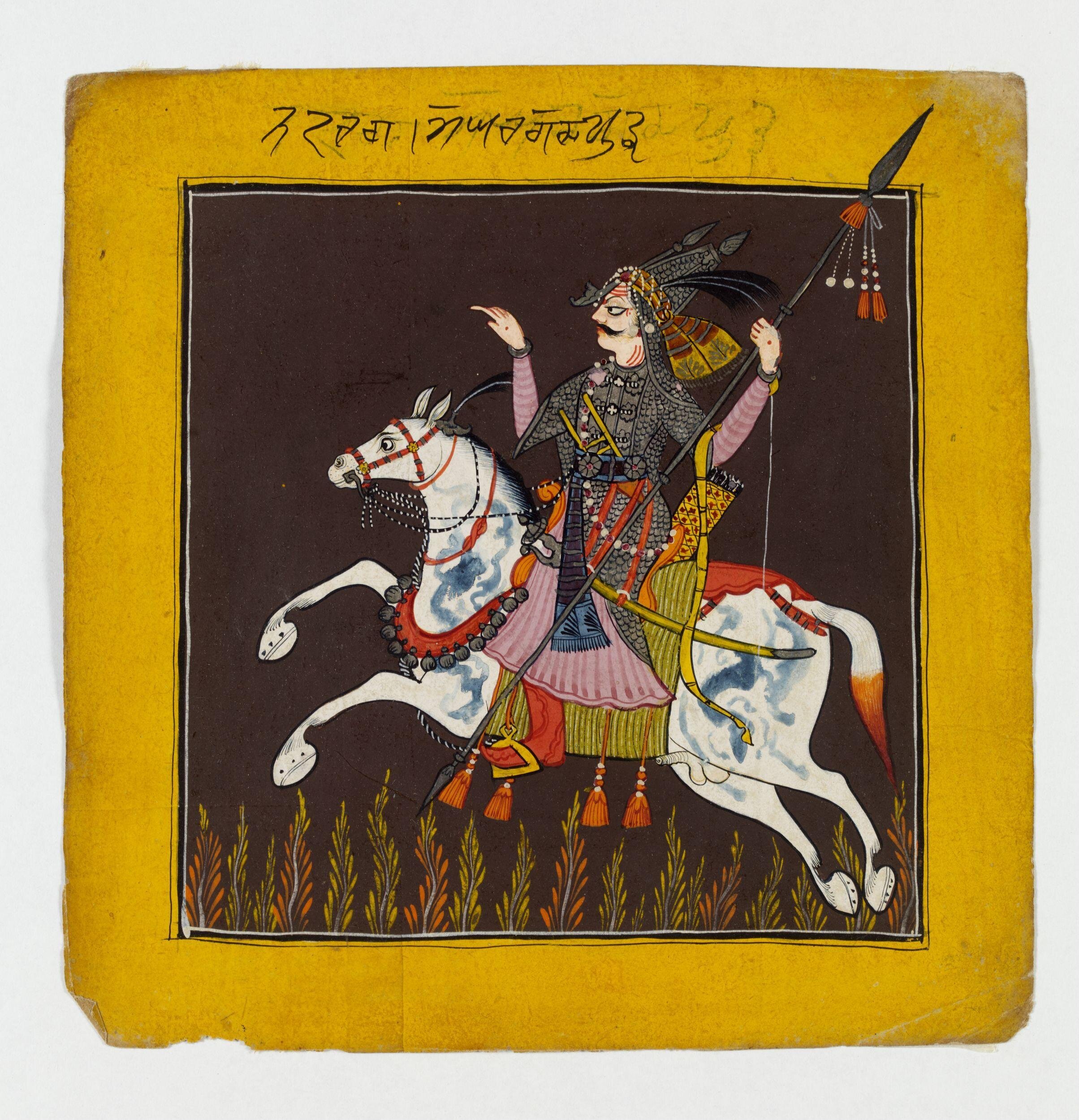

Nata Raga, cr. 1700-10, Kulu, India

Nata Ragini, cr. 1710, Malwa, India

FOLIO FROM A RAGAMALA SERIES: NATA RAGINI, cr. 1750, ?, India

Nata Ragini, Wife of Bhairava Raga, Folio from a Ragamala, 1762, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India

Nata Ragini, cr. 1770, Lucknow, India

Nata Ragini, ca. 18th century, Jaipur, India

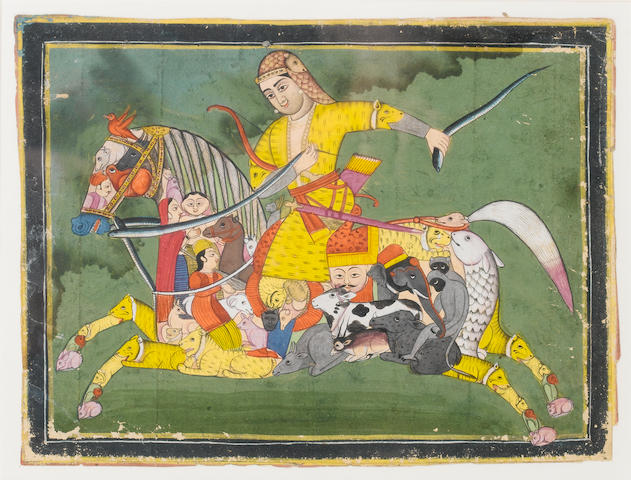

Riders on Composite Horses

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

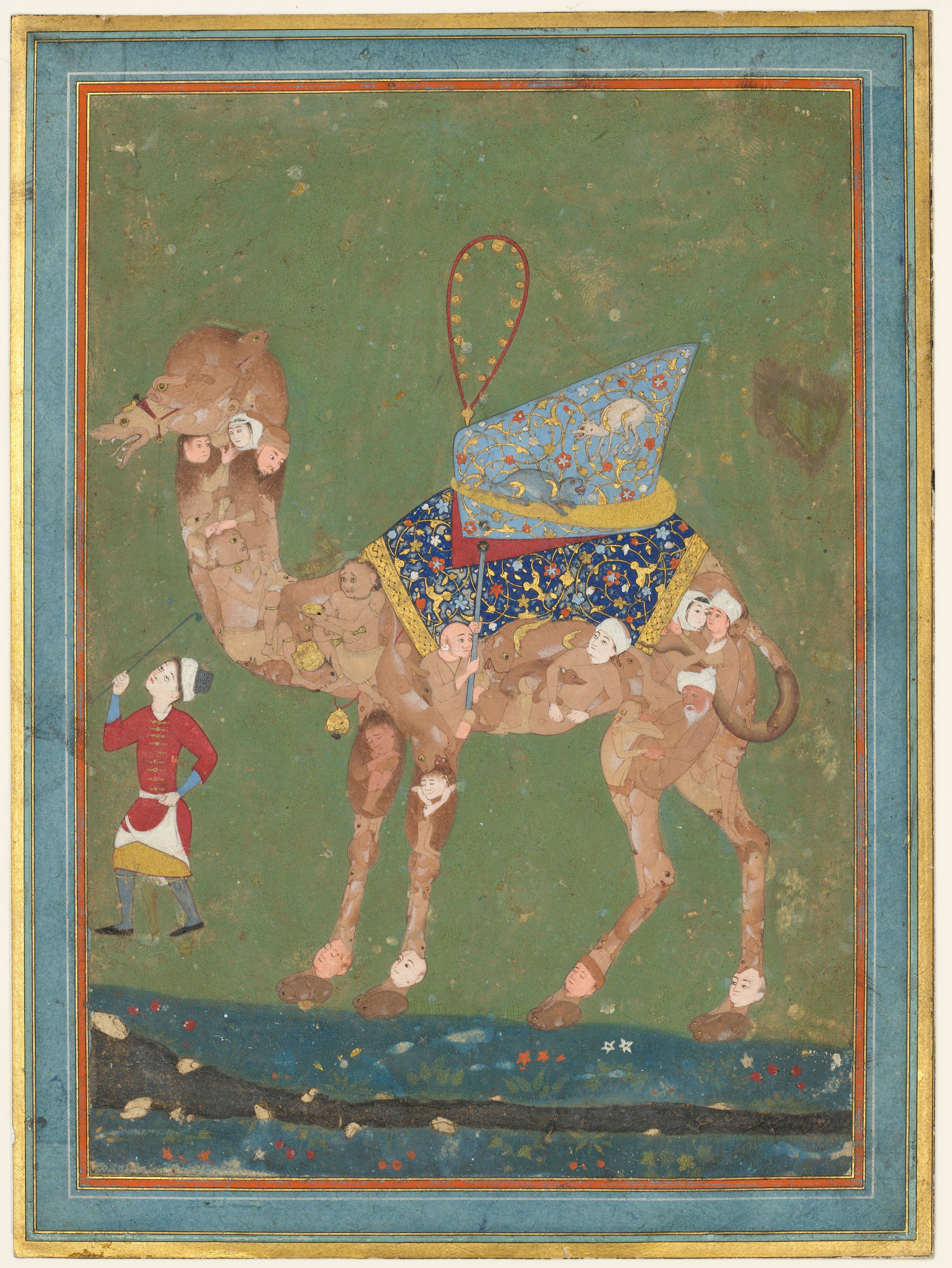

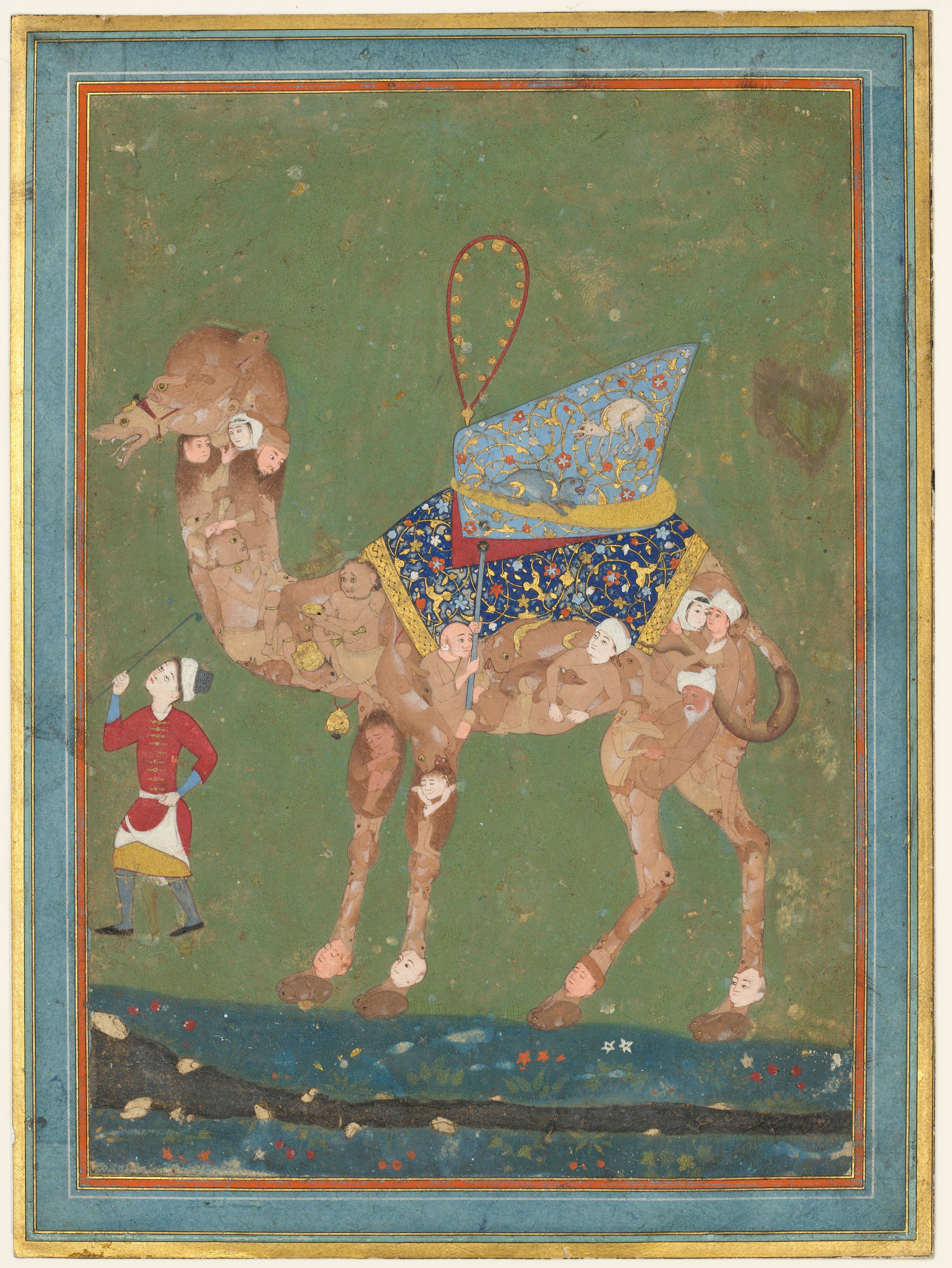

Composite Camel with Attendant, 1550-1575, Khurasan, Iran

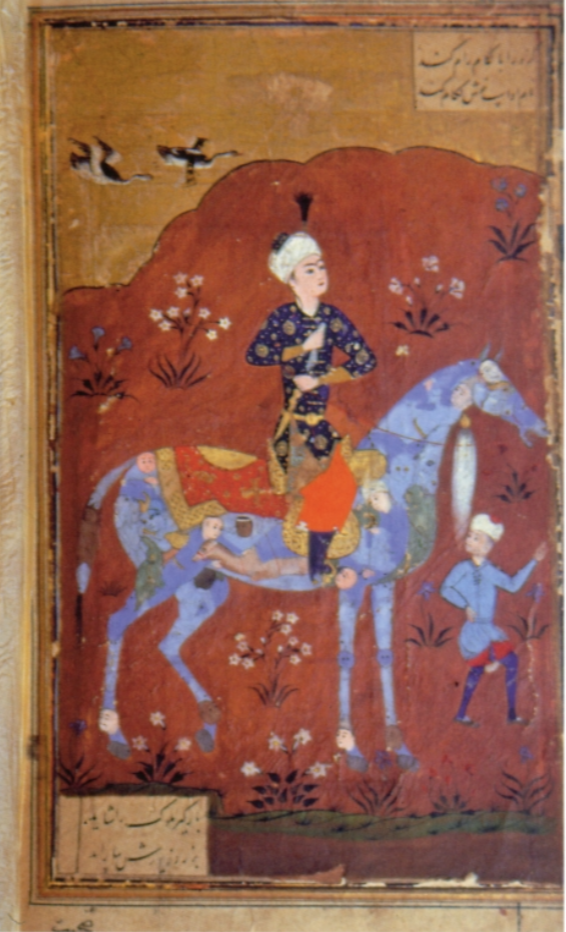

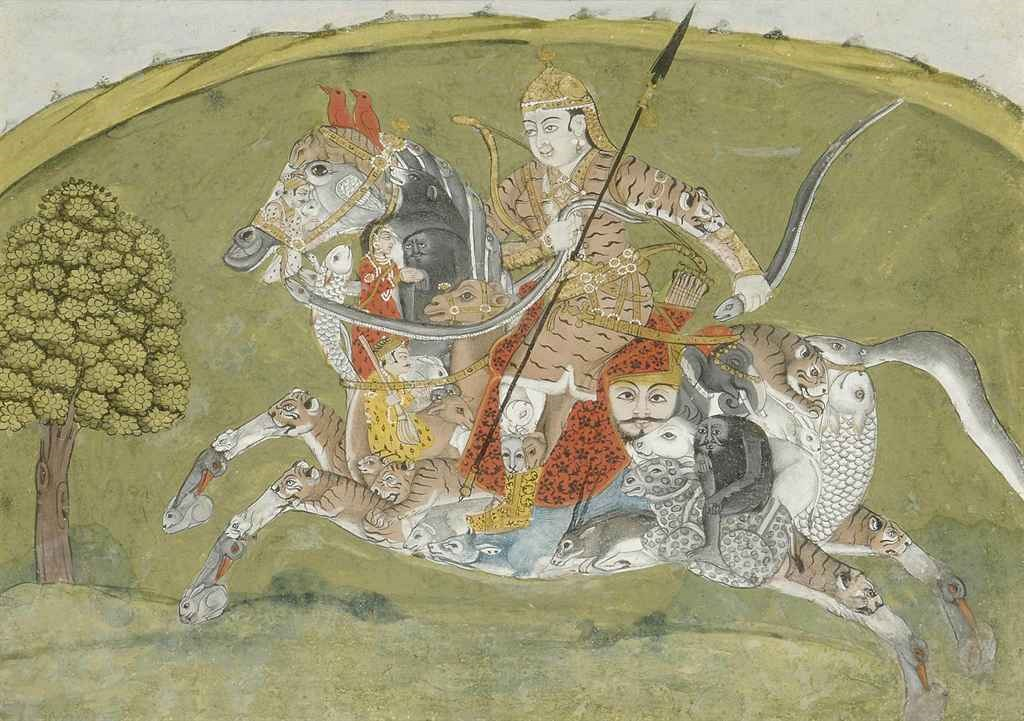

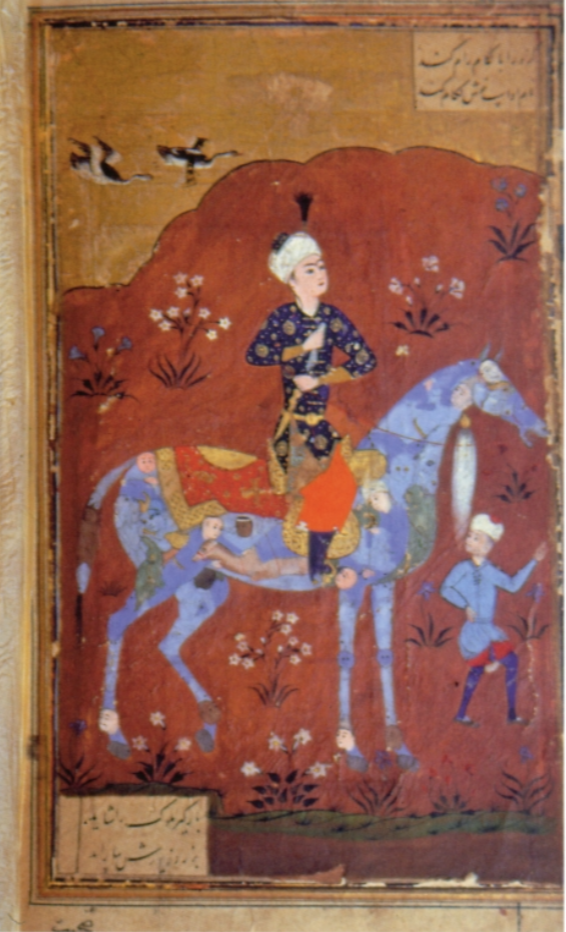

Hunter on a composite horse, illustration to 'Hadiqat al-Haqiqi' (Garden of Truth) by the poet Sana'i, 1569, Herat, present-day Afghanistan, Persian school

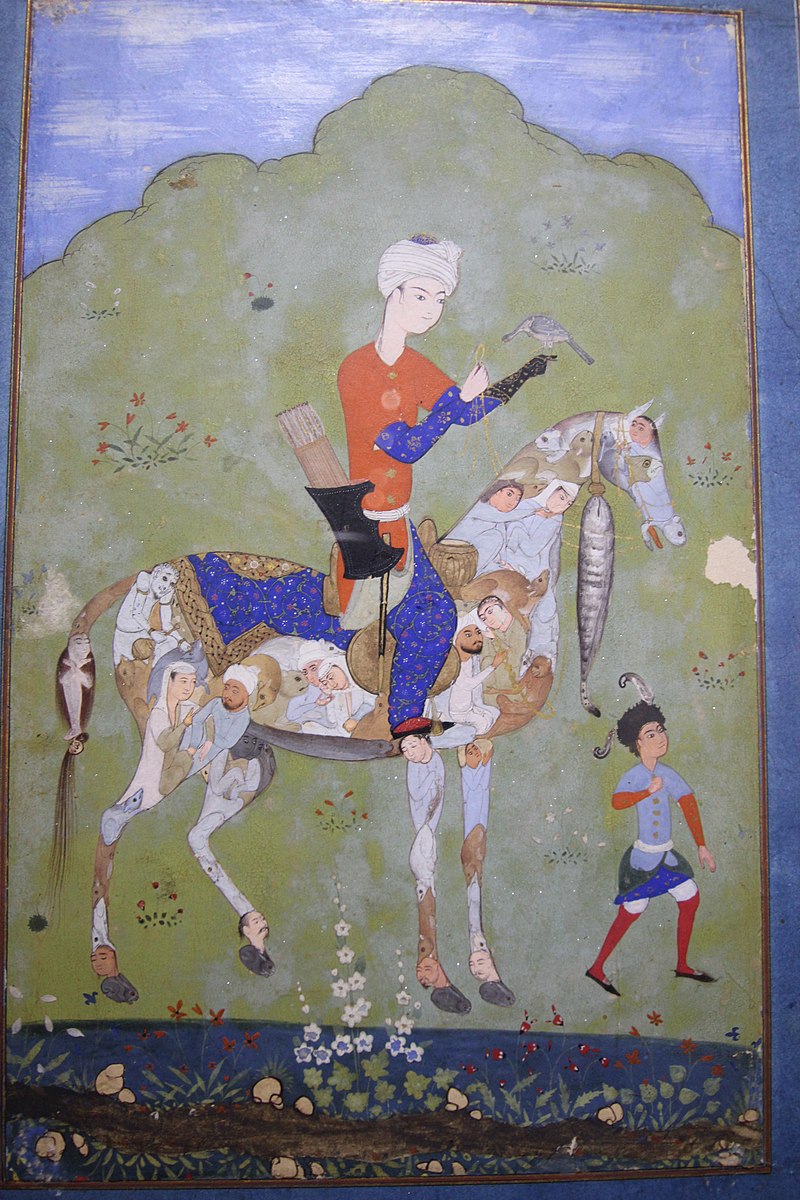

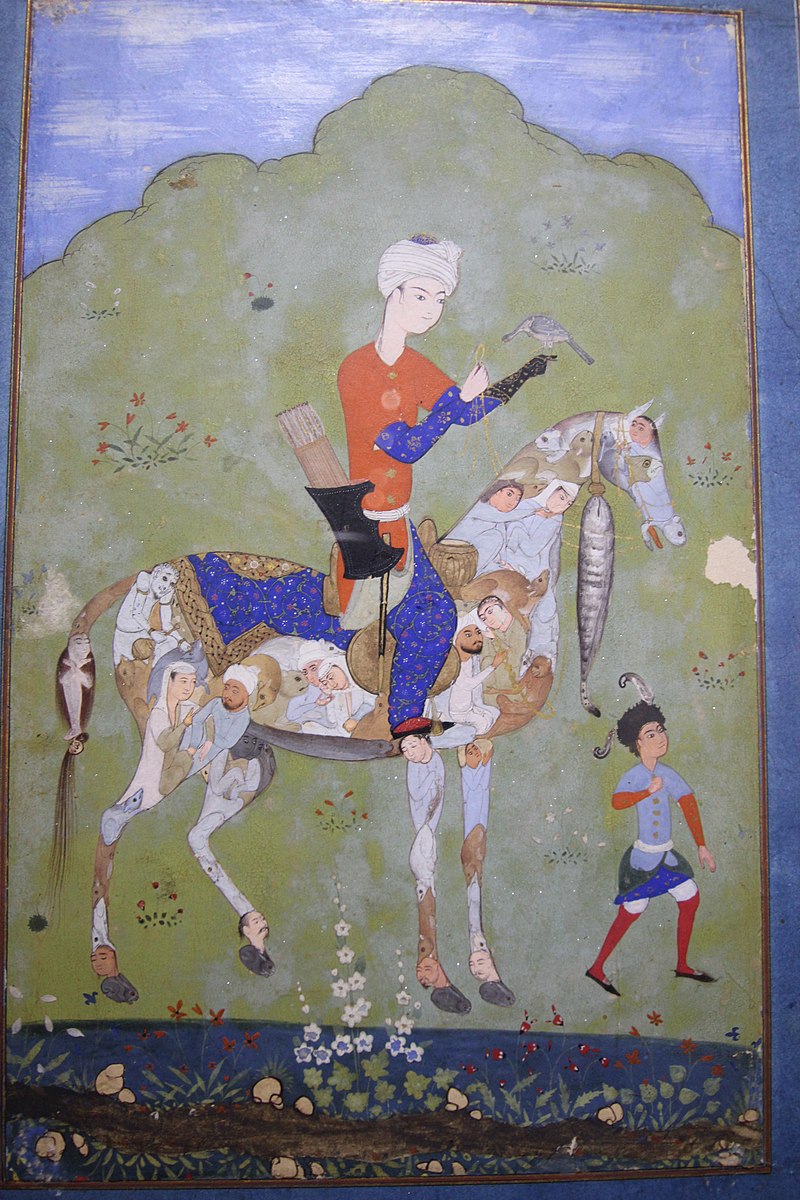

Hunter on a composite horse, illustration to 'Hadiqat al-Haqiqi' (Garden of Truth) by the poet Sana'i, 1573, Khurasan, Iran

A hunter on a composite horse, 16th century, Iran

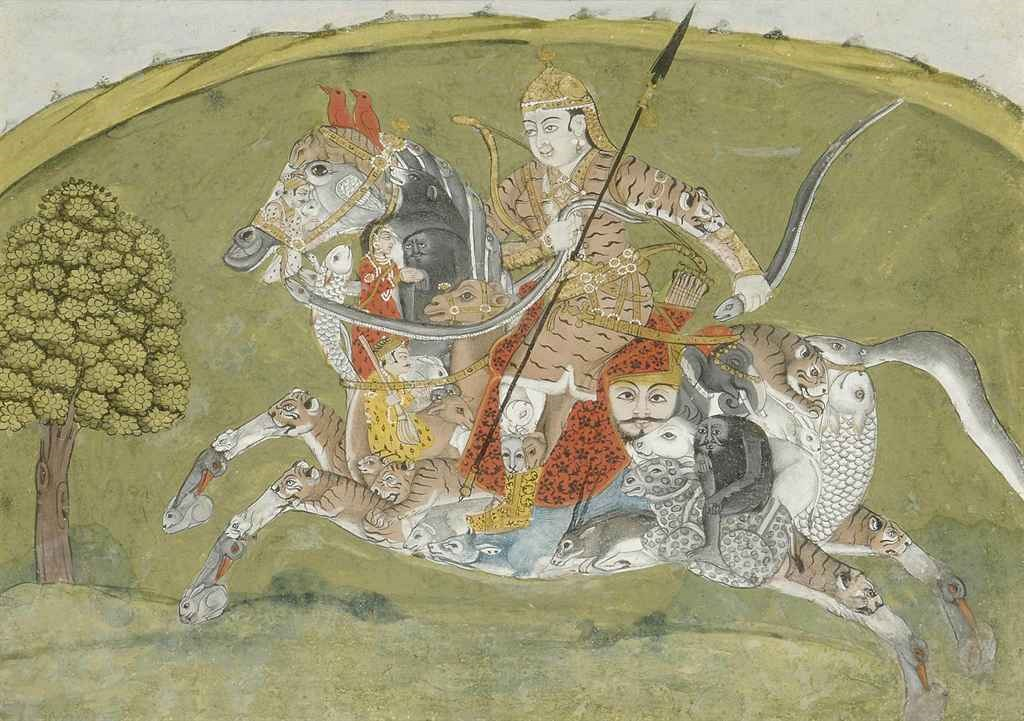

The technique of composite animal painting reached Mughal India through Persian tradition. Interestingly, all three Persian images of a horseman on a rearing horse seem to be illustrating the same book of poems

Hadiqat al Haqiqa, lit. ’The Garden of Truth and The Path to Trek’ is an early Sufi book of poetry written in the Persian language, composed by

Sanai in 1130-31. Moreover, the iconography of these three images is almost identical. However, they are ouf of scope of this work because the horse is not rearing!

According to the Metropolitan museum research, while composite animals are known from earlier periods of Persian art, they gained in popularity toward the end of the sixteenth century. The meaning of such images is open to interpretation, but many scholars believe them to have mystical significance—likely referring to the unity of all creatures within God. According to Saffron art, the other possibility is the representation of the earth spirits, perhaps of Sufi inspiration. The images of demons (divs), dervishes, embracing couples, animals, fish, dragons, and more, can be embedded into the composite animal shape.

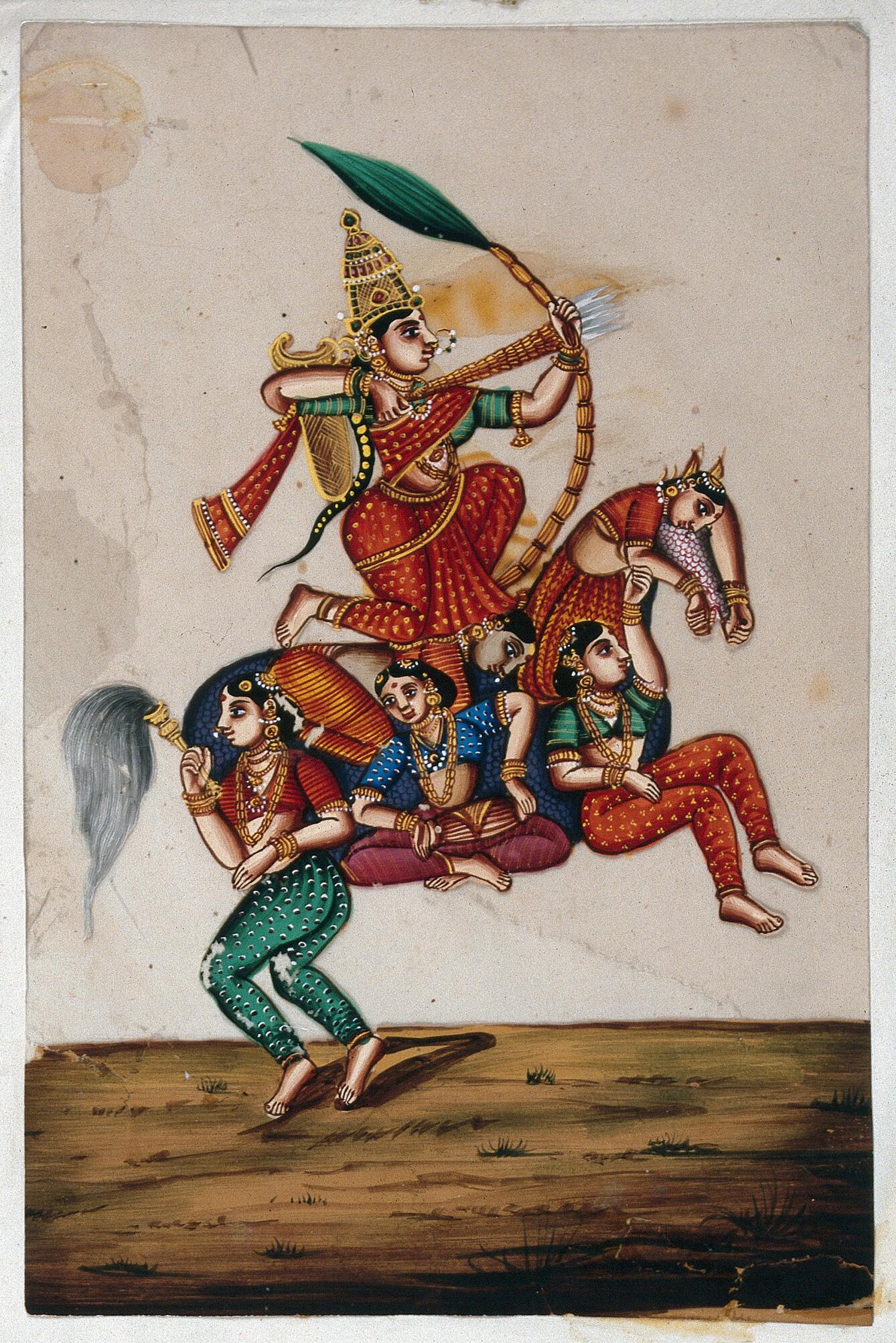

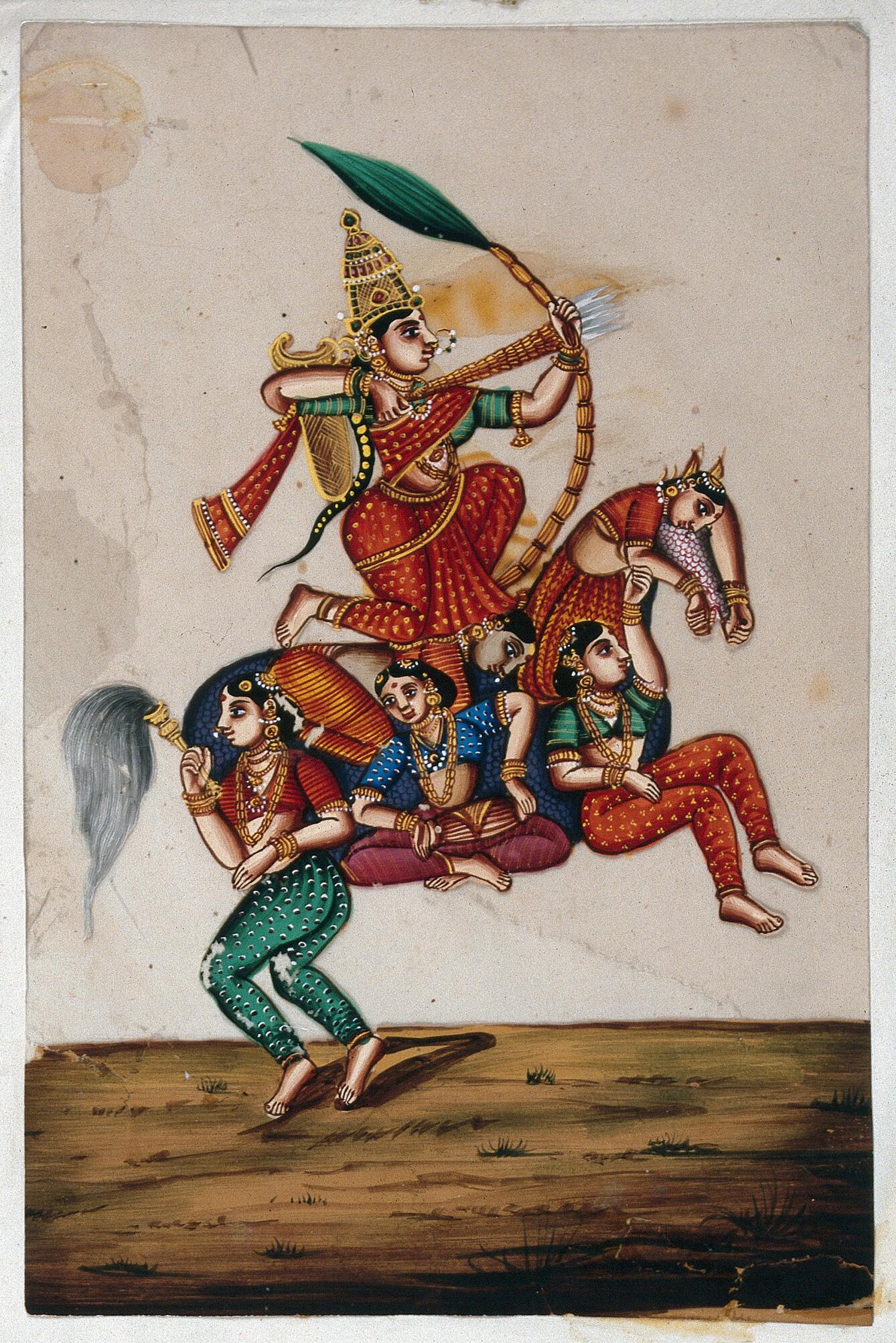

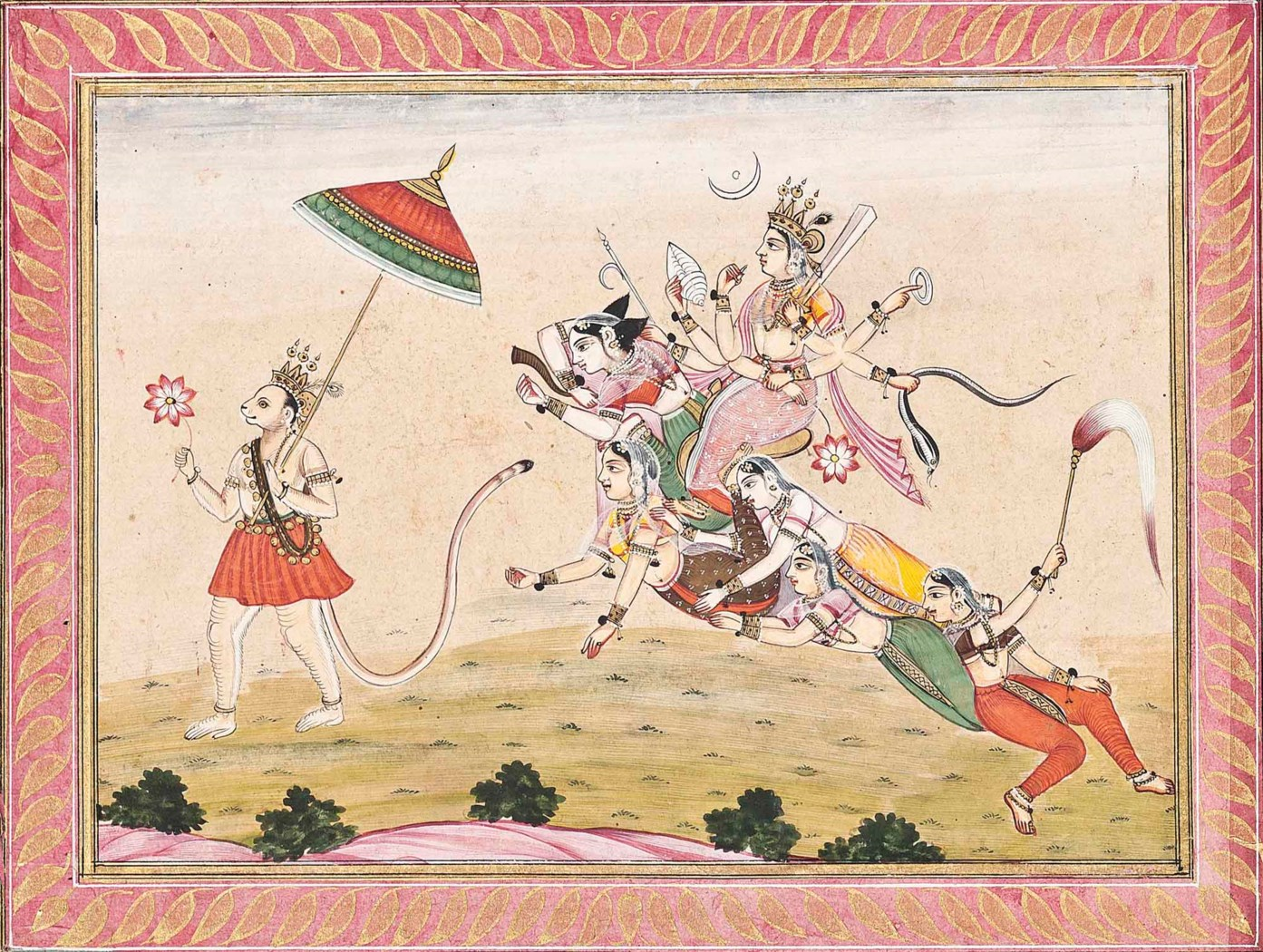

It appears that there are two types of composite horses in Indian subcontitent art. One is made of 5 women. It’s commonly riden by Hindu deities, mostly by Rati, the goddess of love and lust, but also by Krishna, the supreme god, and Durga, the mother goddess. The first image, identified as a princess, could potentially be an image of a goddess, and the composite tiger could actually be a horse, because its “tail” is very similar to the tails of other images in this gallery.

A princess on a composite horse (Narikunjara), 18th century, Mughal school, India

Rati riding a white horse, cr. 1825, Trichinopoly, India

Rati, cr. 1850, Tamil Nadu, India

Rati shooting arrows with a bow while seated on a horse formed from five women, 19th century, India

Krishna Riding a Composite Horse, cr. 1800, Andhra Pradesh, India

Krishna riding a composite horse, 19th century, Nirmal (?), Andhra Pradesh, Deccan, India

A deity (Krishna?) on a composite horse, second half of the 19th century, Delhi, India

Durga riding a composite tiger, mid 19th century, probably Udaipur, Mewar, North India

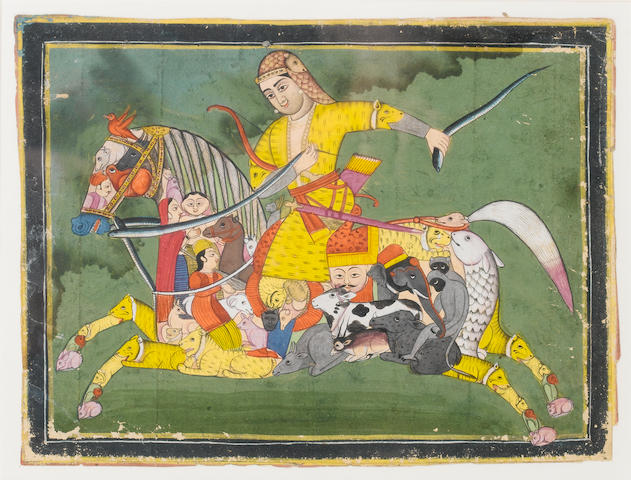

The other type is characterised by horses composed of many different creatures. It’s often referred to as

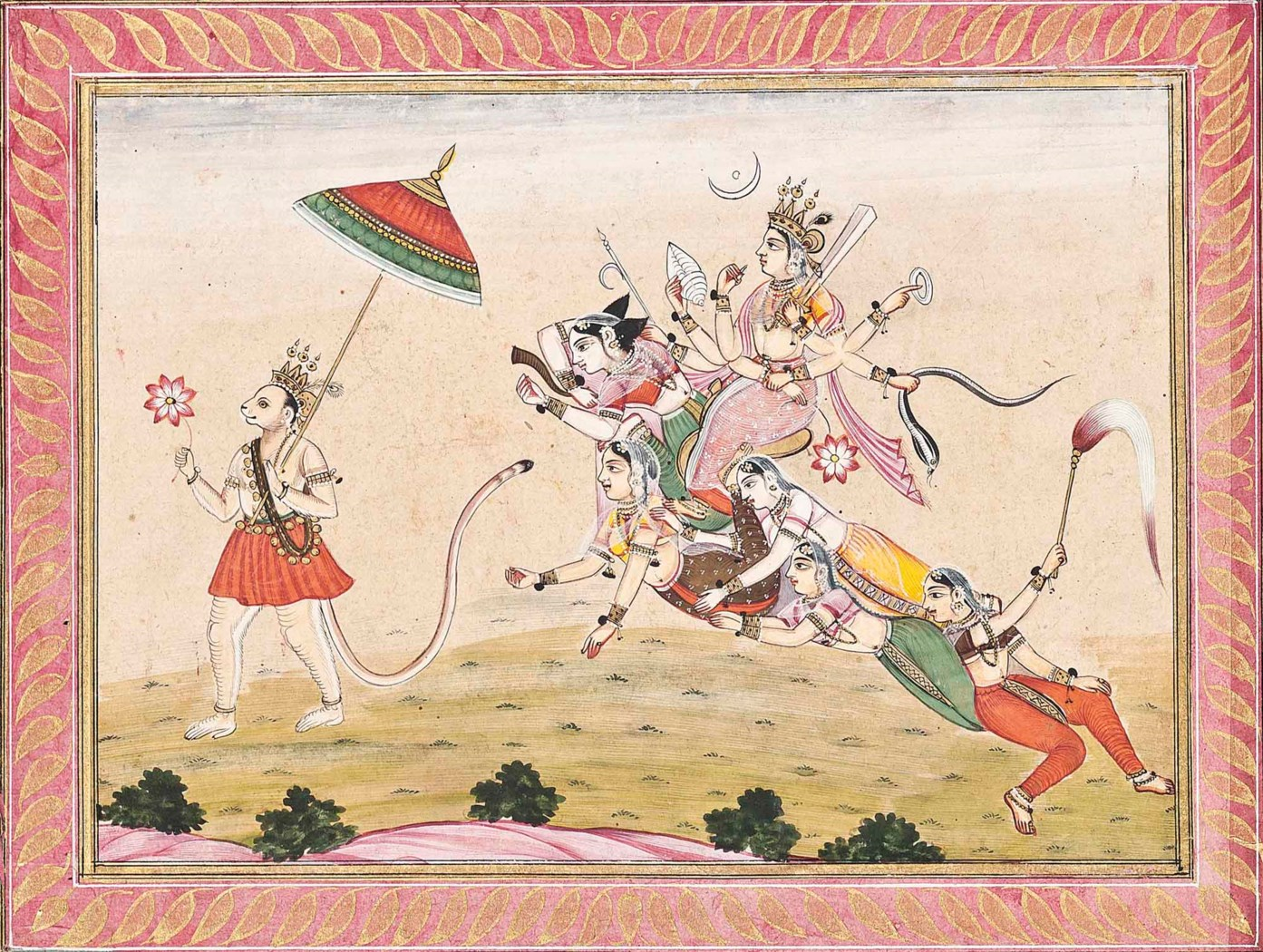

Peri, a winged spirit reknowned for its beauty. While earlier peris are indeed very beautiful and feminine (addition of a compsite dog running next to the composite horse is a very touching detail), we can see that its image has transformed with time: it loses its wings, its feminine beauty was replaced by an intimidating image of a warrior, she holds one or two smakes and her horse’s reins are made of snakes.

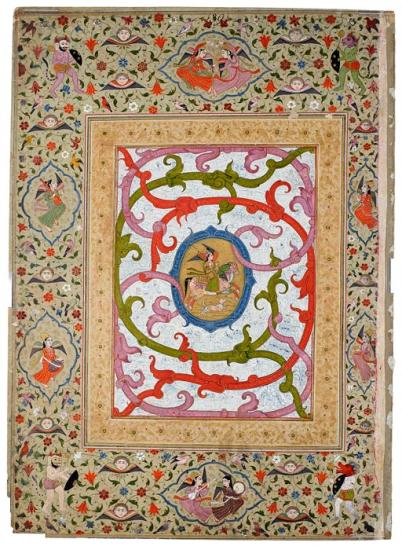

A peri riding a composite horse, circa 1700, Pahari school, possibly Basohli or Mankot, North India

Peri riding a composite horse, second half of the 18th century, Mughal, possibly Kashmir, India

Peri riding a composite horse (detail), second half of the 18th century, Mughal, possibly Kashmir, India

A peri rides a composite horse across a field, cr. 1760, ?, India

Pari on a composte animal, 19th century, Deccan, India

Composite horse with a female rider, late 18th century, Murshidabad, India

A princess cantering on a composite horse, circa 1800, by Zafar Ali Khan, Delhi, India

A rider on a composite horse, early 19th century, Rajahstan, India

A princess dressed as a warrior riding a composite horse, early 19th Century, Gwalior or Indor, India

A warrior riding a composite horse, mid 19th century, Jaipur, India

A warrior galloping on a composite horse, 19th century, India

A warrior galloping on a composite horse, 19th century, India

Composite horse and rider, 19th century, India

Company Style, 18th And Early 19th Century

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Company style, also known as Company painting is a term for a hybrid Indo-European style of paintings made in India by Indian artists, many of whom worked for European patrons in the East India Company or other foreign Companies in the 18th and 19th centuries. For obvious reasons, these images were not glorifying Indian military achievements, but we can find a large number of Hindu deities riding white horses

Kubera riding a white horse, cr. 1814, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

Kubera riding a white horse, cr. 1820-25, Tiruchirapalli, Tamil Nadu, India

Rati riding a white horse, cr. 1825, Trichinopoly, India

Khanderao (also known as Khandoba) and his consort Mhalsa riding a white horse, cr. 1830, Tiruchirapalli, Tamil Nadu, India

Kubera riding a white horse, cr. 1830, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

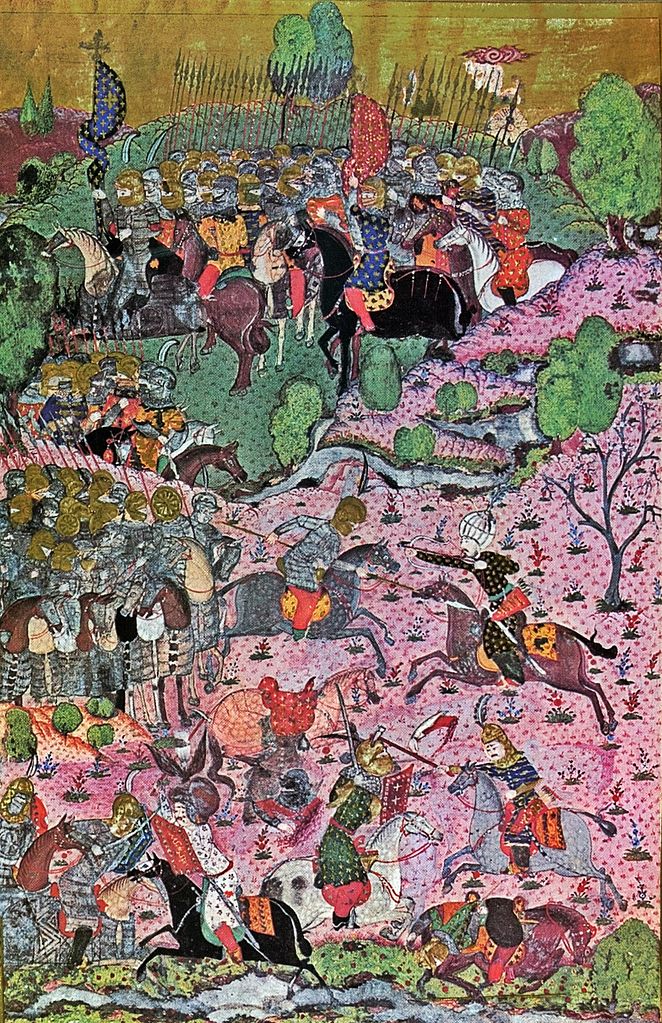

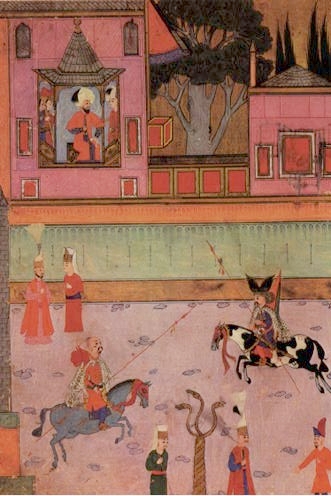

Manuscript Illustrations Of Ottoman Empire, 16th century

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1923) controlled much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia and North Africa between the 14th and early 20th centuries. The Ottomans ended the Byzantine Empire with the 1453 conquest of Constantinople. Its defeat in World War I resulted in its partitioning and the loss of its Middle Eastern territories, which were divided between the United Kingdom and France. The successful Turkish War of Independence led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk against the occupying Allies led to the emergence of the Republic of Turkey in the Anatolian heartland of the Ottoman monarchy.

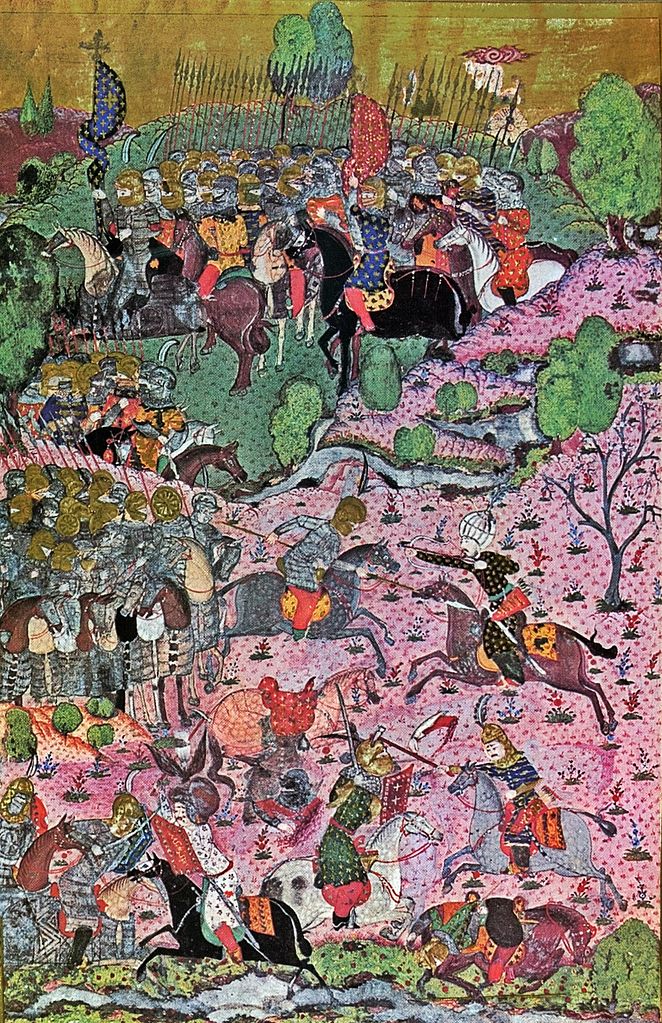

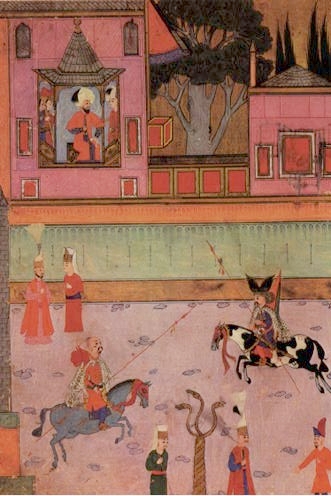

Ottoman miniature was a Turkish art form in the Ottoman Empire, which can be linked to the Persian miniature tradition, as well as strong Chinese artistic influences. The golden age of the Ottoman miniature was the second half of the 16th century, this is when we see quite a few illustrations featuring the rearing horsemen. The later artists were preferring calmer, more static subjects.

Topkapi palace, 1523, Istanbul, Ottoman Empire

Battle_at_Lipova, 1551, second half of the 16th century, Ottoman Empire

Duel before the Battle of Mohács, 16th century, Ottoman Empire

Battle of Mohács, 16th century, Ottoman Empire

Parade of two riding Gazi (veterans from Rumelia) in front of Sultan Murat III, 16th century, Nakkaş Osman and/or other painters of the Nakkaşhane, Ottoman Empire

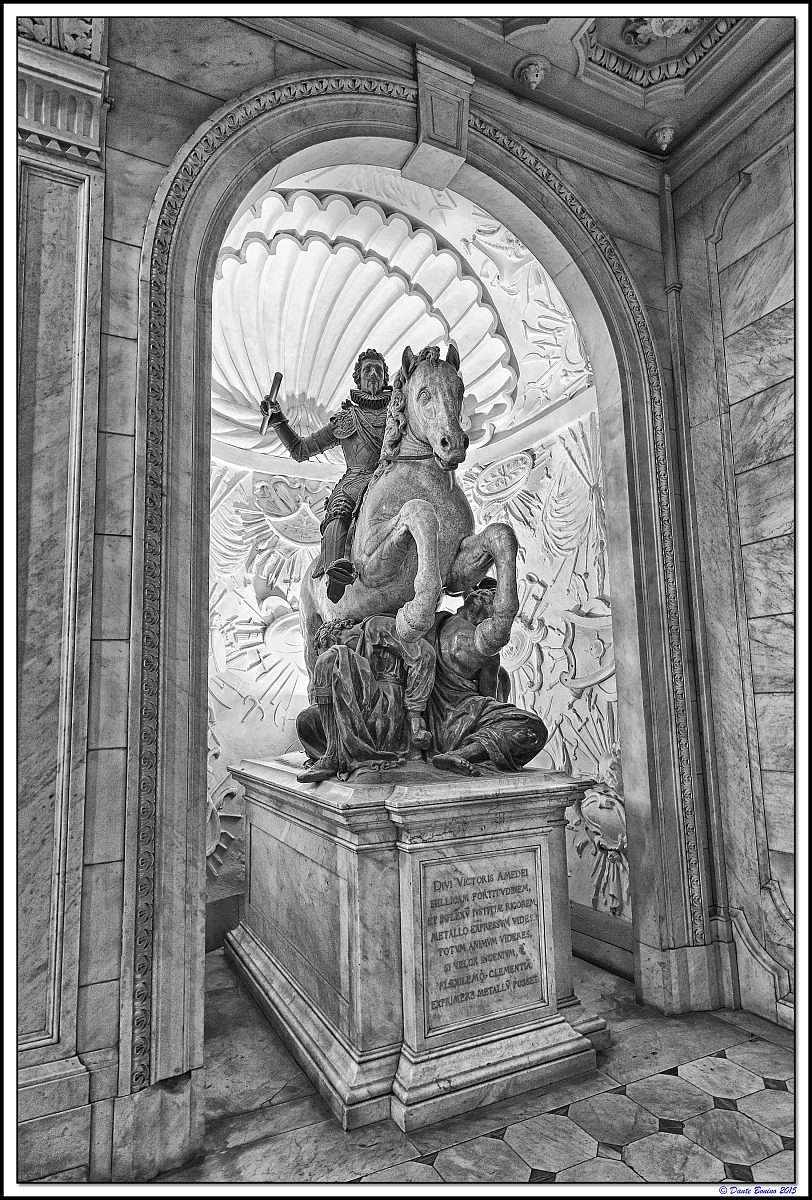

The House of Savoy, 17 to 19 century

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Map of Italy in 1494

Map of Italy in 1843

Map of Italy in 1864

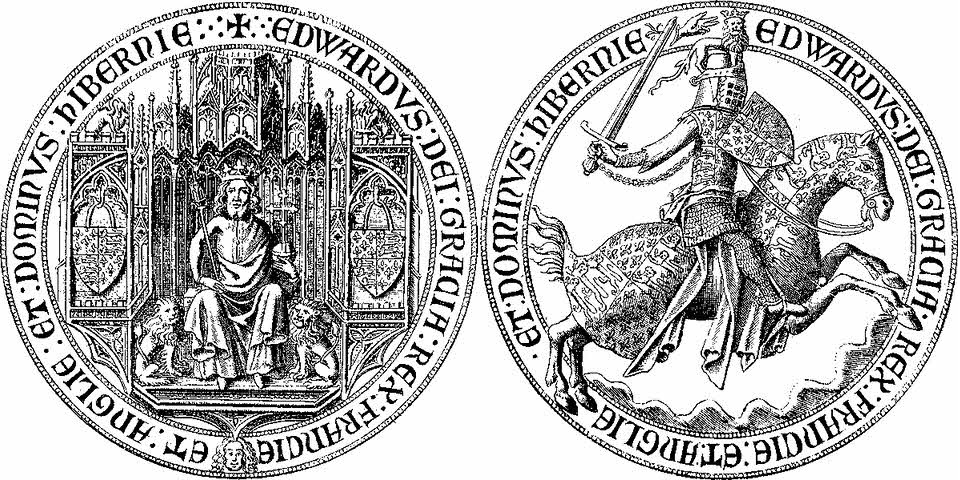

The

Duchy of Savoy has disappeared from the European map, but it used to be one of the greatest European powers. The

House of Savoy is one of the oldest royal families in the world (it was founded in 1003). Initially, it was a small county in Savoy (a region between Italy and France). It gradually expanded through annexation of the neighbouring territories, and in 1416 it became a duchy. For 7 years, from 1713 to 1720, it included Sicily. In 1720 the Duke of Savoy was forced to exchange his throne in Sicily for that of the less important

Kingdom of Sardinia. Ironically, it was Sardinia that would later unify Italy in the nineteenth century, and the junior branch of the house of Savoy was ruling the

Kingdom of Italy since from creation in 1861 till 1946 when Italy became a republic.

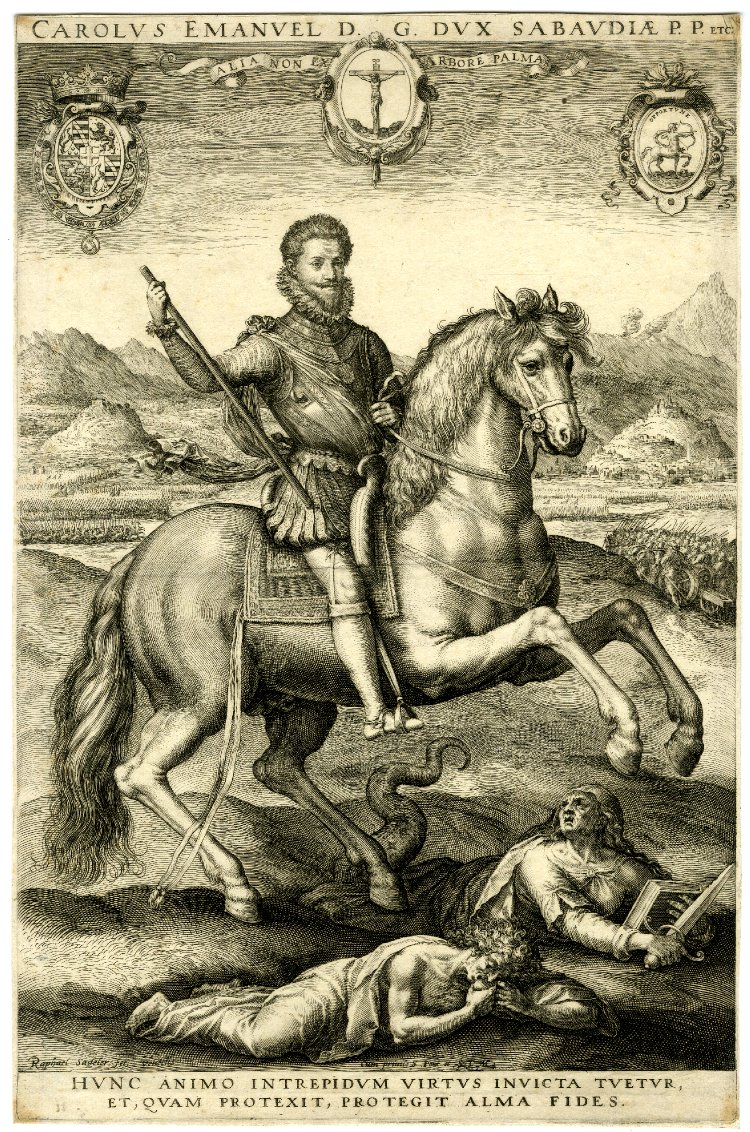

Depictions of Dukes and A Duchess of Savoy on rearing horses

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

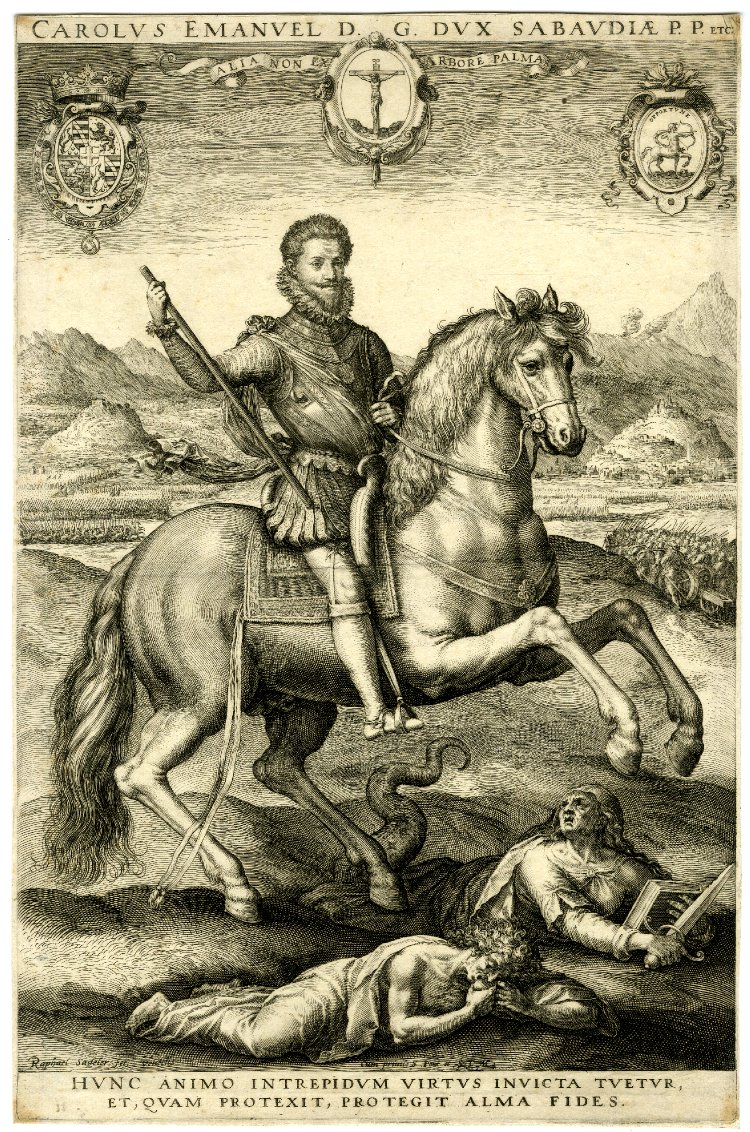

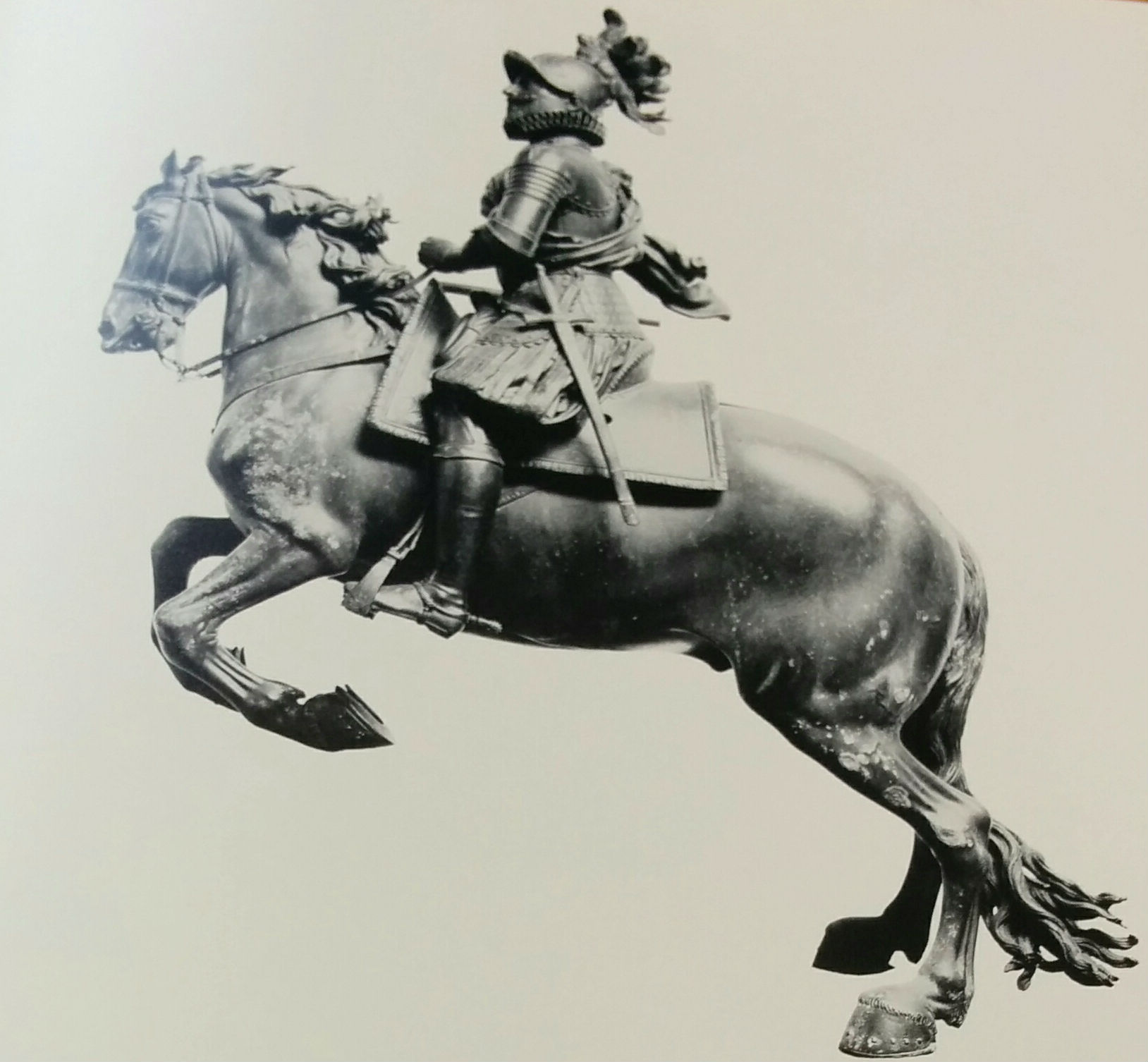

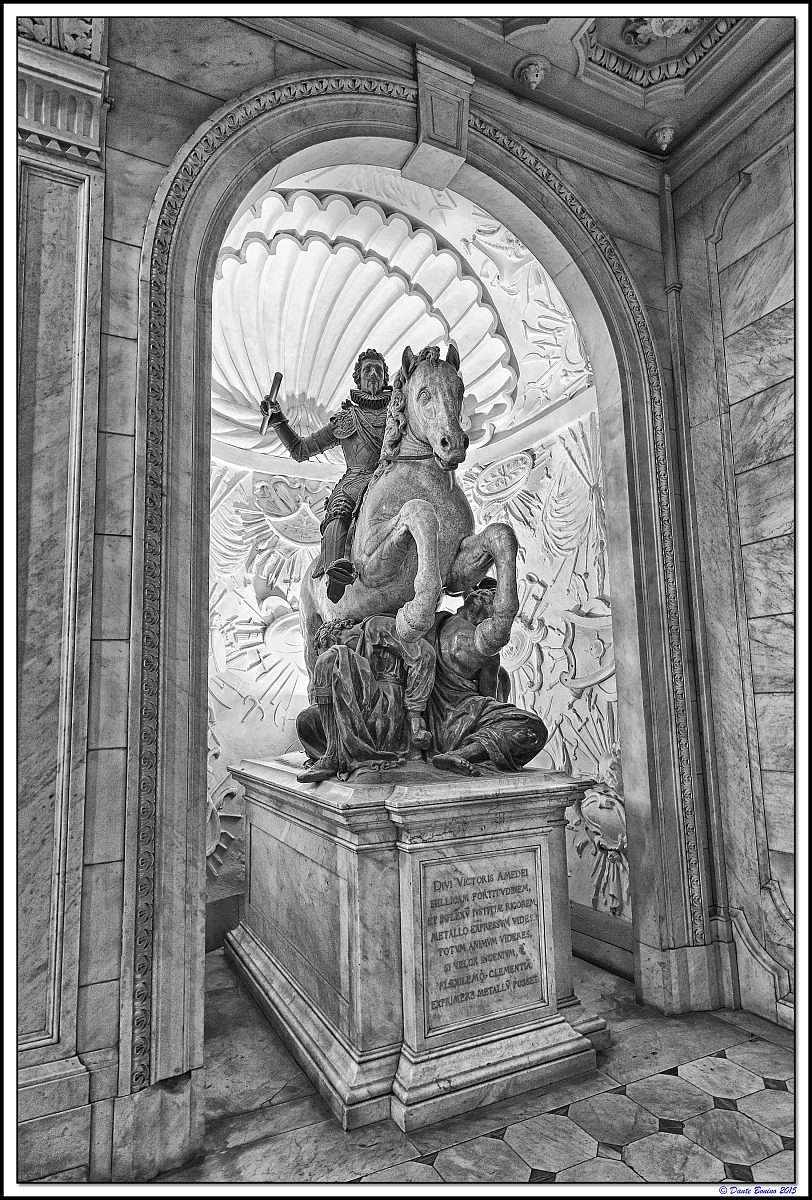

Several Savoy rulers have been portrayed on rearing horses…

Equestrian portrait of Carlo Emmanuele, Duke of Savoy, 1580-1600, Raphael Sadeler I

Equestrian monument of Carlo Emmanuele, Duke of Savoy, 1619-21, Pietro Tacca

Equestrian portrait of Prince Tomaso of Savoy-Carignan, son of Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, 1634-5, Anthony van Dyck

Statue of Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy, 1620s and 1660s, Andrea Rivalta and Federico Vanelli

Equestian portrait of Marie Jeanne Baptiste of Savoy-Nemours, Duchess of Savoy, 1660-75, Giovanni Luigi Buffi, Duchy of Savoy

Equestrian portrait of Carlo Emmanuele II of Savoy with his son and heir Vittorio Amedeo, Prince of Piedmont, 1673, Giovanni Battista Brambilla

Equestrian portrait of Charles Emmanuel III, Duke of Savoy and King of Sardinia, 1720-61, Maria Giovanna Clementi, Turin, Italy

Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663 – 1736)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The most portrayed member of Savoy house was not a ruler. Prince Eugene of Savoy was born in Paris. The great-grandson of Charles Emmanuel I grew up around the French court of King Louis XIV. Because of a scandal involving his mother, he was rejected for service in the French army. Eugene moved to Austria and transferred his loyalty to the Habsburg Monarchy, and became a general of the Imperial Army and statesman of the Holy Roman Empire and the Archduchy of Austria and one of the most successful military commanders in modern European history.

Equestrian portrait of Prince Eugene of Savoy, early 18th century, Jacob van Schuppen

Eugene of Savoy during the Battle of Belgrade (1717), cr. 1720, Johann Gottfried Auerbach

Portrait of Prince Eugene of Savoy, cr. 1725, unknown painter (Johann Gottfried Auerbach?)

Statue of Prince Eugene of Savoy, 1865, Vienna

Spain and its colonies: Royalty And Saint James, 15th-21st Centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Spanish Painters, 17th-19th Centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Diego Velázquez (1599 – 1660)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The most significant and famous equestrian Spanish portraits were made by Diego Velázquez. He seems to have adopted the iconography developed by Peter Paul Rubens.

Philip IV on Horseback, 1631-6, Diego Velázquez

Equestrian Portrait of Prince Balthasar Charles, 1634-5, Diego Velázquez

Equestrian Portrait Of The Count-Duke Of Olivares, 1634, Diego Velázquez

Philip III on Horseback, 1634-5, Diego Velázquez

Prince Baltasar Carlos with the Count-Duke of Olivares outside the Buen Retiro palace, 1636, Diego Velázquez

Francisco Goya (1746 – 1828)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Hunting Party, 1775, Francisco Goya

The Count-Duke Of Olivares, engraving based on Velázquez's portrait, 1792, Francisco Goya

The other very famous Spanish painter who has created a number of interesting portraits of horsemen on the rearing horses is

Francisco Goya. Goya was familiar with Diego Velázquez’s equestrian portraits, and have even made several engravings based on these paintings. However, his paintings are strikingly different. Whereas the sitters seem to be pleasant, there is no sense of confidence, no more scintillating colours; the palette is muted, the composition is quite simple, but there is some sense of psychological ambiguity; the sitters, despite all their victories and other achievements, appear as simple mortals.

These portraits are very different from joyful and luminous (the reproduction does not do this painting justice) “Hunting Party” executed by Goya earlier in his career.

Sketch for the equestrian portrait of Manuel Godoy, Duke of Alcudia, 1794, Francisco Goya

Equestrian Portrait of Fernando VII of Spain, 1808, Francisco Goya

Equestrian Portrait of the 1st Duke of Wellington, 1810s, Francisco Goya

General José de Palafox on Horseback, 1814, Francisco Goya

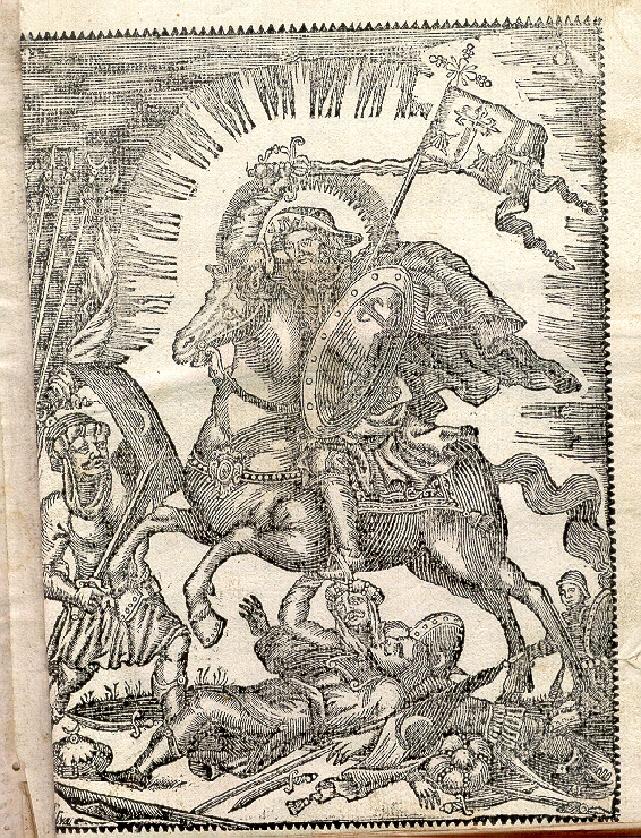

Saint James the Moor-slayer, a.k.a. Santiago Matamoros, 15th-21st centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Who is Saint James, a.k.a. Santiago?

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

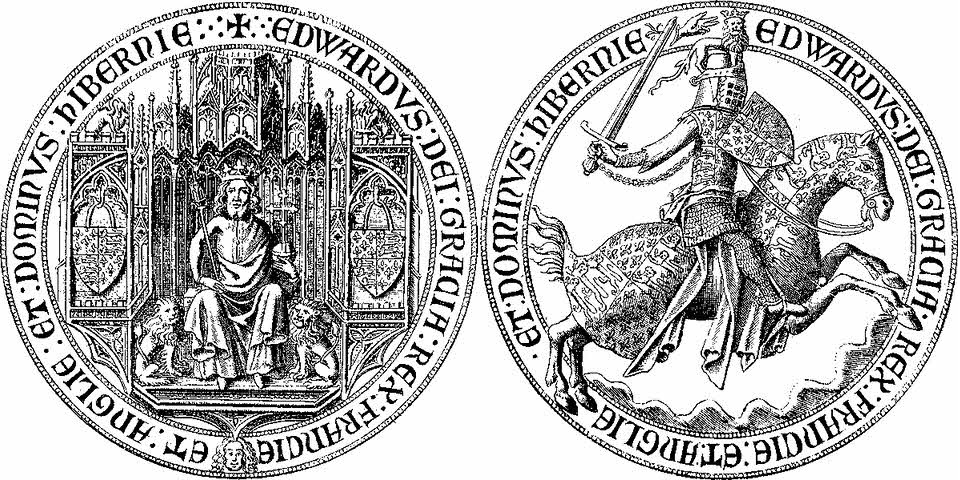

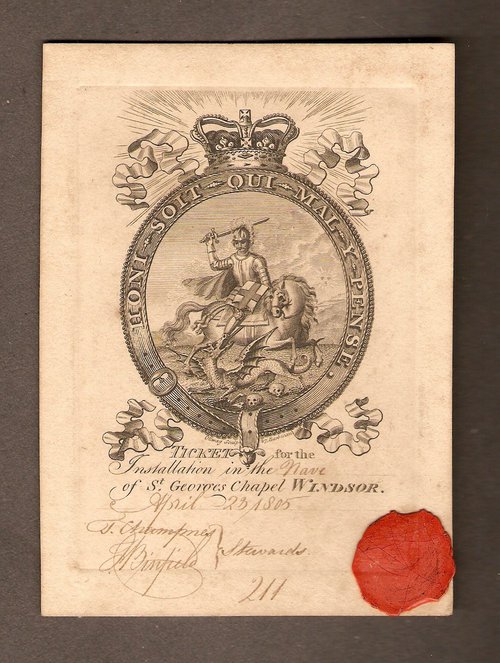

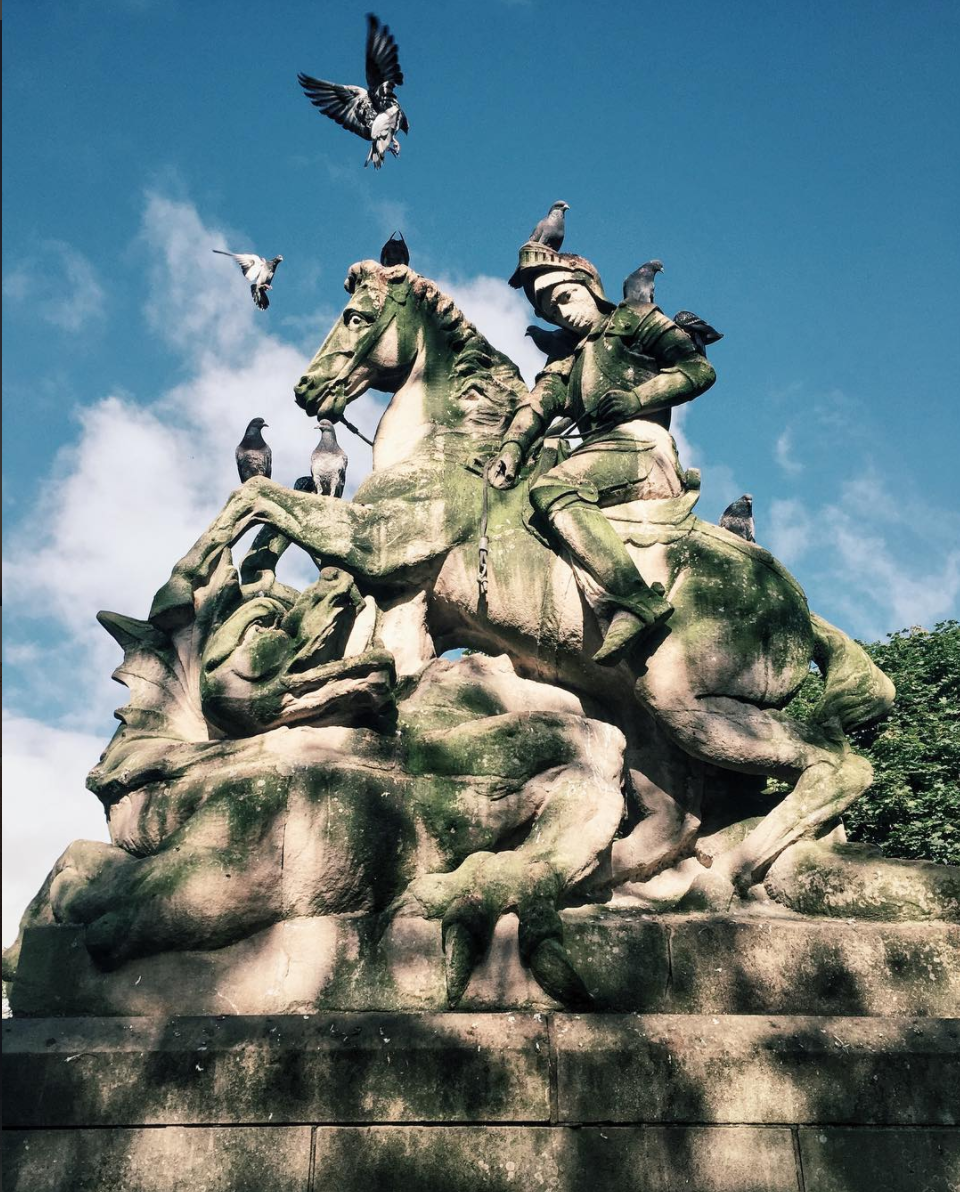

James the Great was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus, and is the patron saint of Spaniards. According to legend, his remains are held in Santiago de Compostela in Galicia. (The name Santiago is the local evolution of Vulgar Latin Sanctu Iacobu, “Saint James”, with San Diego also being a derivative of Santiago.)

Saint James the Moor-slayer (Spanish: Santiago Matamoros) is the name given to the representation (painting, sculpture, etc.) of the apostle James as a legendary, miraculous figure who appeared at the also legendary Battle of Clavijo, helping the Christians conquer the Muslim Moors. The Battle of Clavijo is a mythical battle that, apparently, never took place, but was a subject of many legends. Aspects of the historical Battle of Monte Laturce (859) were incorporated into this legend.

Unlike the courtly paintings, we have seen before, the paintings that resulted from the cult of Saint James were sincere and appealing to all layers of the society. The quality of these works vary a lot, they are often anonymous. Their quantity is quite astonishing: what you see below is only a small part of a very large body of works devoted to Saint James the Moor-slayer.

Santiago Matamoros in Spain, 15th – 20th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Santiago Matamoros In Paintings

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Even though there were paintings of Santiago Matamoros before the 17th century and outside Spain, it was in Spain and in the 17th century that this saint became an object of cult.

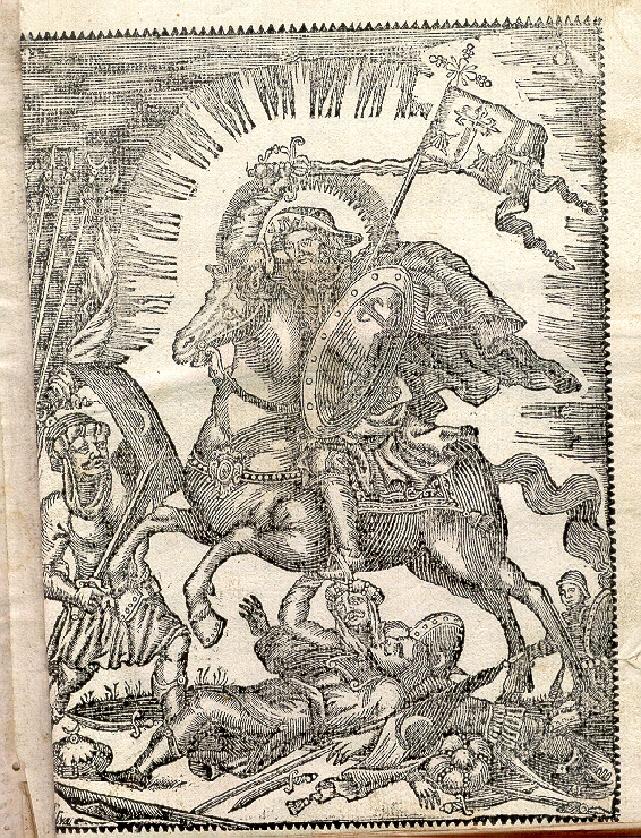

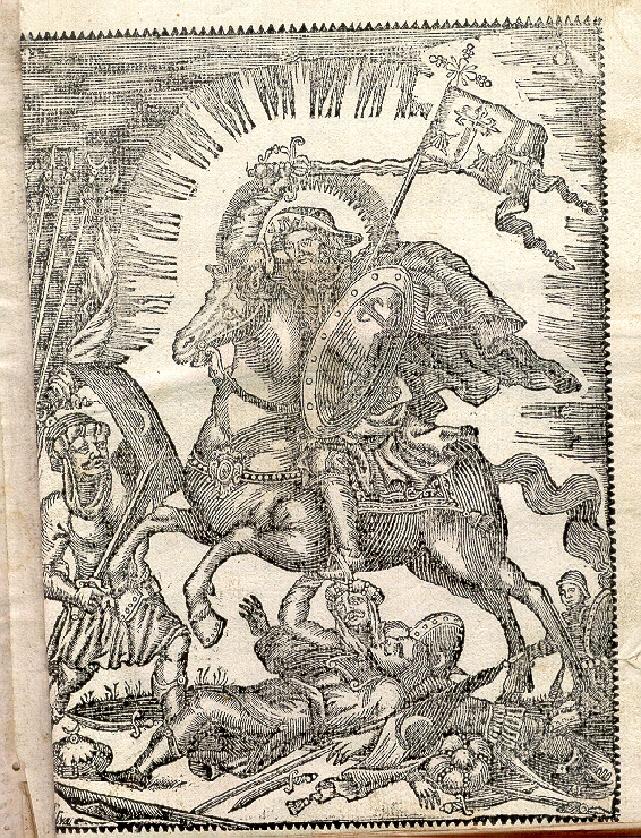

COMPARANDUM: The Battle of Clavijo (mythical, 844), autumn 1471 - spring 1473, Martin Shongauer, Alsace, Germany

Altarpiece with St. James in the central panel, 15th century, Segovia, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, 15th century, Santa María de Labrada, Guitiriz, Lugo, Spain

Apostle Santiago in the battle of Clavijo, end of the 16th century, Mateo Pérez de Alesio, Church of Saint James, Seville, Spain

Apostle Santiago in the battle of Clavijo, 1609, Juan de las Roelas, Cathedral of Seville, Spain

The Apostle Santiago on horseback, or Santiago Matamoros, 1649, Francisco Camilo, Spain

Apostle Santiago fighting the moors, 1690, Lucas de Valdés, Córdoba, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, 1747, Jacobo de la Piedra, Spain

Apostle Santiago in the battle of Clavijo, cr. 1753-62, Ginés Andrés de Aguirre, after Corrado Giaquinto, Spain

Apparition of Apostle Santiago in the battle of Clavijo, 18th century, Antonio González Ruiz, Cuenca, Spain

Santiago Matamoros In Sculptures And Reliefs

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

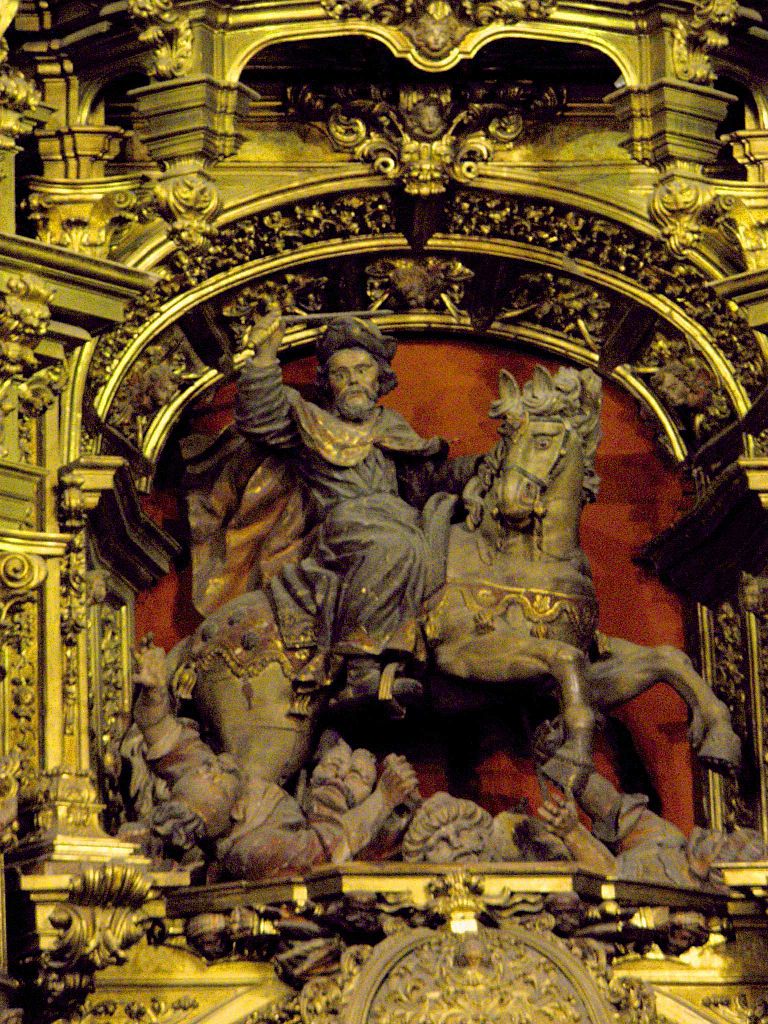

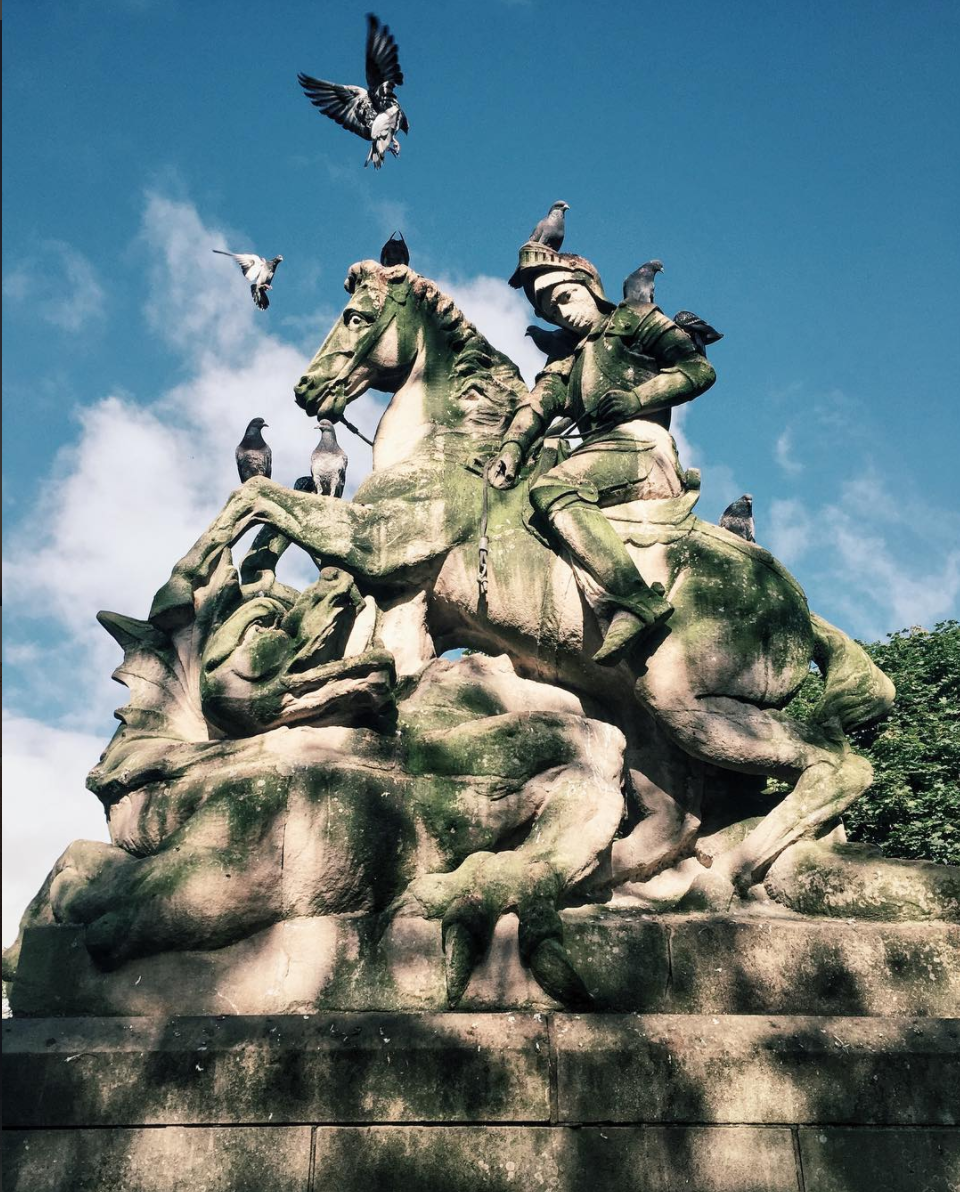

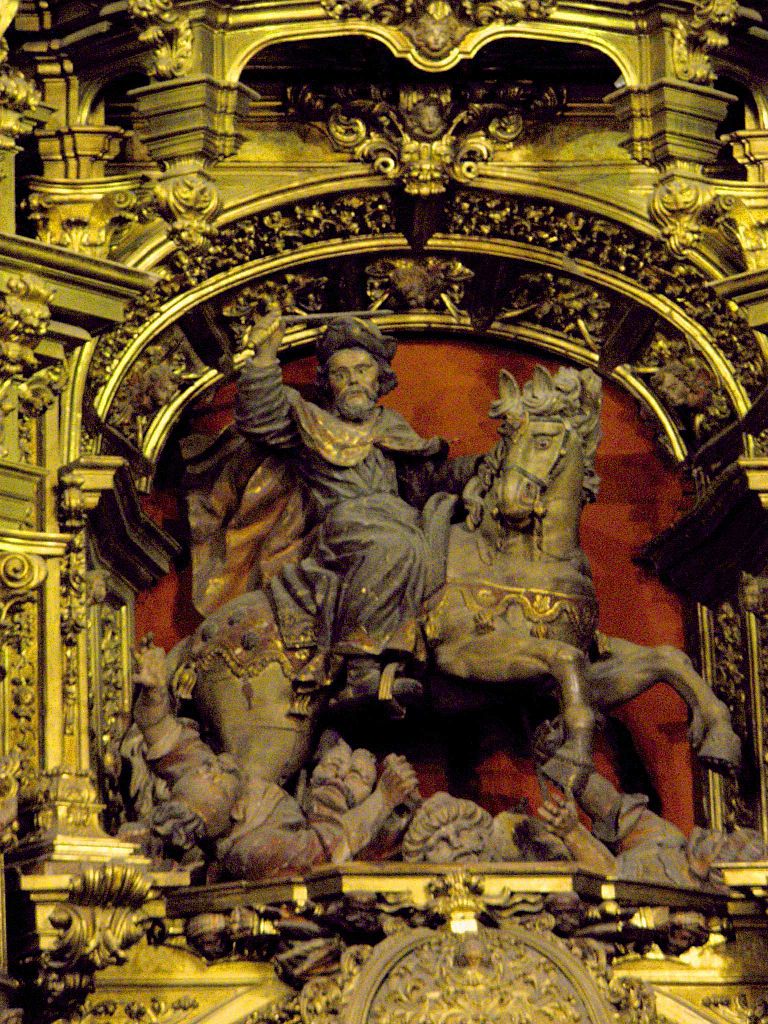

There are many statues of Santiago Matamoros in Spanish churches, especially in Castile and León and Galicia. The most famous one is located in Santiago de Compostela Cathedral in Galicia; this cathedral is the reputed Santiago’s burial place.

Santiago Matamoros, 16th century, Church of Santa María la Real, Sasamón, Burgos, Castile and León, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, 17th century, ?, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, second half of 17th century, Juan de Ávila (1652-1702), church of Santiago Apóstol, Valladolid, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, 18th century, Altarpiece of Santiago de Compostela Cathedral, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Zaragoza, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Altarpiece of the Chapel of St. John the Baptist and St. James, Cathedral of Burgos, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Losar de la Vera, Cáceres, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Iglesia Arzobispal Castrense, Madrid, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Ermua (Vizcaya), Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Calahorra, La Rioja, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Capela da Misericordia, Baiona, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Mezquita Cathedral, Cordoba, Spain

In addition, several sculptures and relieves of Santiago Matamoros adorn facades of public buildings in Spain.

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Hospital de Sant Jaume i Santa Magdalena, Mataró, Barcelona, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Convento de las Comendadoras de Santiago, Madrid, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Colegio Mayor de Santiago el Zebedeo, Salamanca, Castilla y León, Spain

Santiago Matamoros, ?, Hospital del Rey-Universidad, Burgos, Castilla y León, Spain

Santiago in Americas: Matamoros, Mataindios and Mataespañoles, 17th – 21st centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Santiago in Americas

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

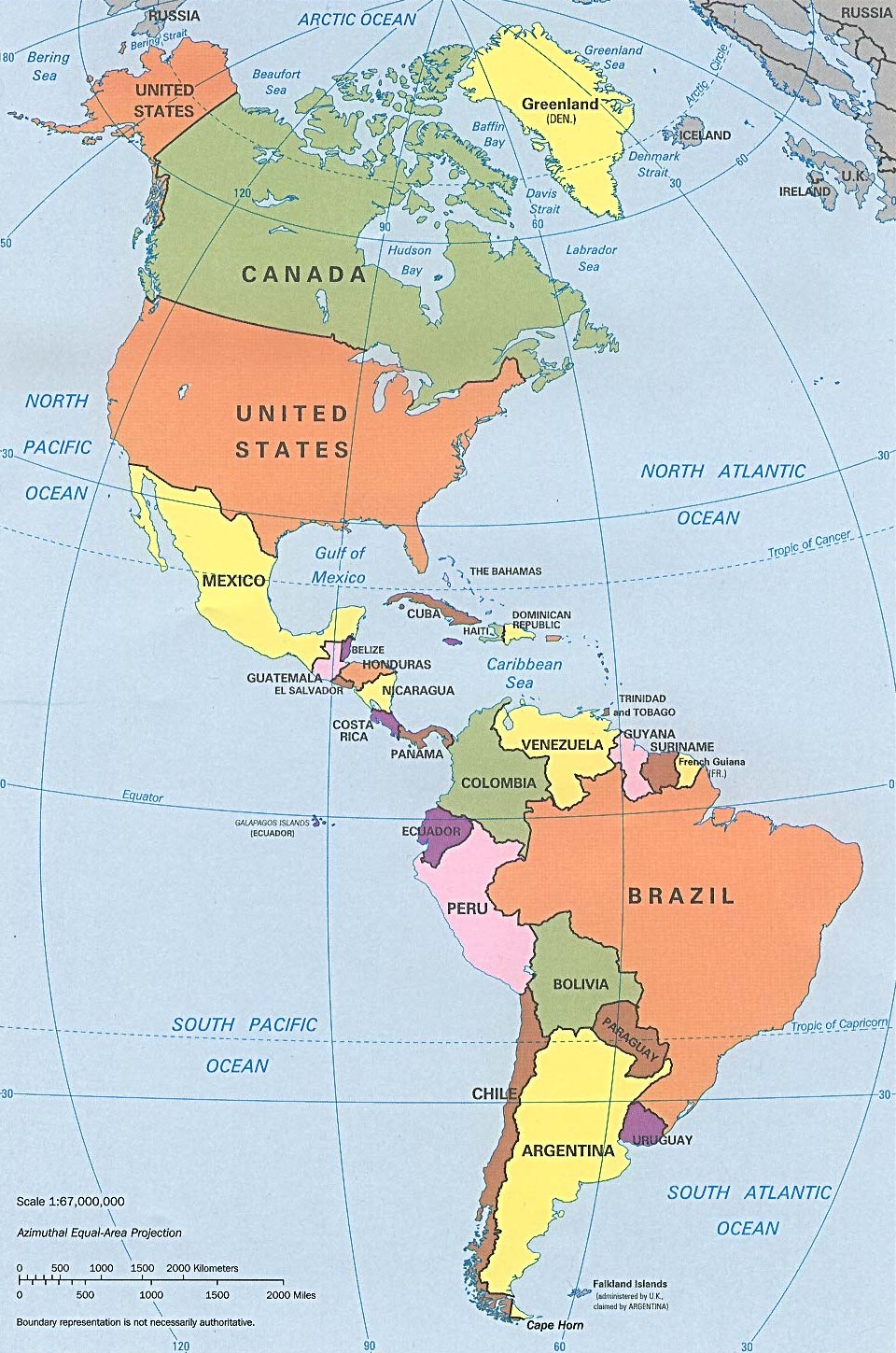

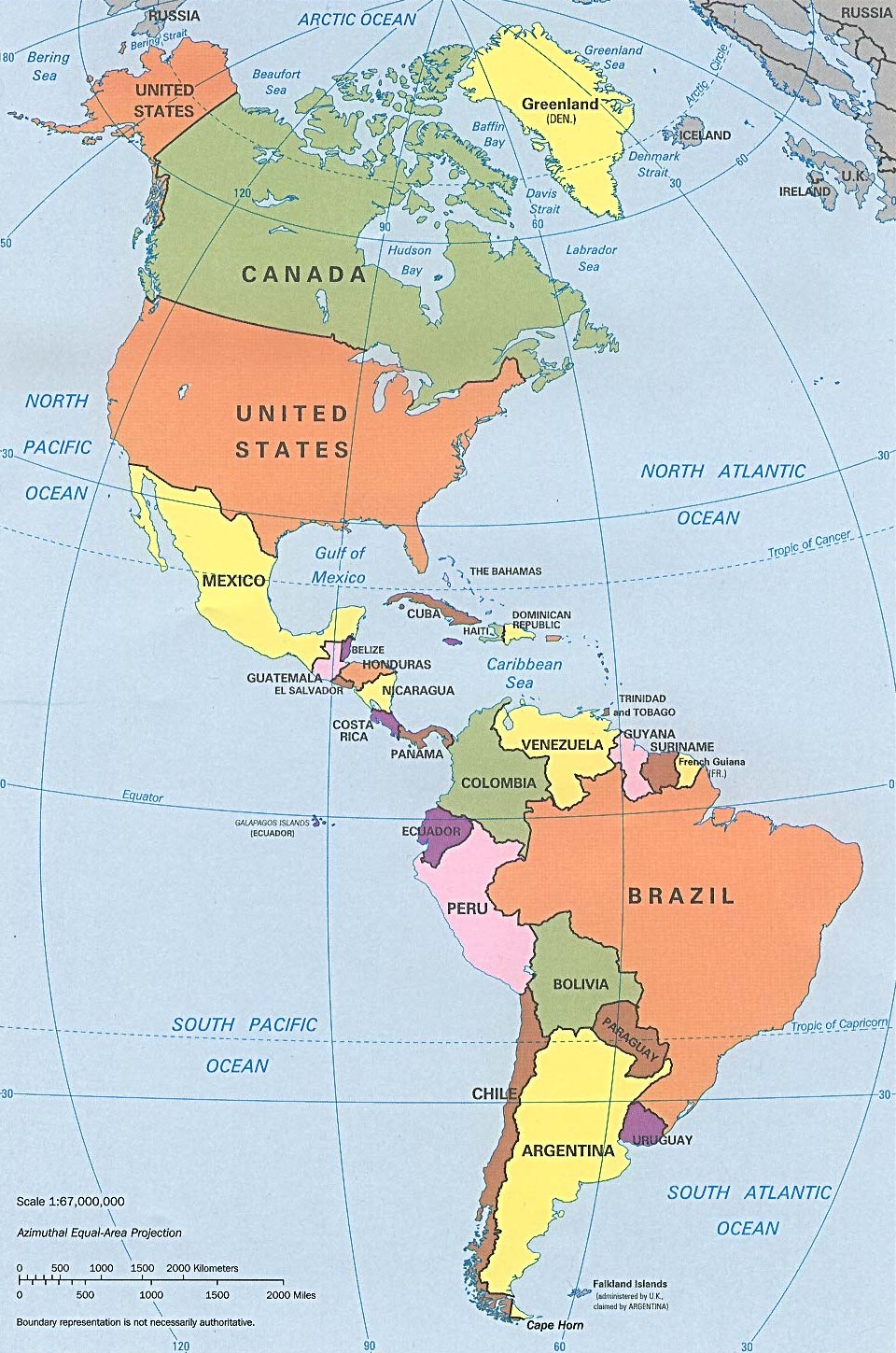

Contemporaty political map of Americas

Map of Spanish Americas at the end of the 18th century

Cusco, location within Peru

Santiago was “exported” to the other side of Atlantic ocean during the

Spanish colonization of the Americas (1492-1832). He was an extremely popular figure there, almost always represented on a rearing horse, slaying the enemies. As we will see, there were three “incarnations” of Santiago in Americas: Matamoros, Mataindios and Mataespañoles.

Cuzco School

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Many works in this section were done by the artists belonging to Cusco School (sometimes spelt as “Cuzco School”). This was a Roman Catholic artistic tradition based in Cusco, Peru (the former capital of the Inca Empire) during the Colonial period, in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. It was not limited to Cusco only, but spread to other cities in the Andes, as well as to present-day Ecuador and Bolivia. Specific characteristics of Cuzco school are: the neglect of the perspective, the fragmentation of the space in several concurrent scenes, the preference for intense colours typical of the aesthetics of those countries, the presence of Andean flora and fauna, and the introduction of characters dressed in the manner indigenous, such as caciques and Inca warriors. This school originated from the work of several Indian and mestizo painters, who transmitted their particular vision of the world through a simple technique, sometimes rough and naive, that adapted the western plastic language. Like Ionian Greek artists when Ionia was invaded by Persians, Peruvian artists were creating the art objects that were glorifying their invadors, but retained some key stylistic features of their native culture.

Santiago Matamoros

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Santiago Matamoros, 1670-90, Peru

Patron Saint victorious over the moors, 17th century, Peru

St. James panel from reredos in Cristo Rey Church, cr. 1760, Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S.A.

Santiago Matamoros, second half of 18th century, Venezuela

Santiago Matamoros with the Christ of the three spears, 18th century, Peru

Portrait of Philip V as Saint James, 18th century, Bolivia

Santiago Matamoros, 18th century, colonial school

Santiago Matamoros, 18th century, colonial school

Santiago Matamoros, 18th century, colonial school

Santiago Matamoros and pastoral life scene, early 19th century, Peru

Sculpture of Saint James, colonial era, Mexico

Wood relief of Saint James, colonial era, Mexico

Santiago Matamoros (polychrome alabaster), 20th century, Peru

Santiago Matamoros (alabaster), 20th century, Peru

Santiago Matamoros (alabaster), 20th century, Peru

Sculpture of Saint James, 1996, Abraham Gonzalez, Mexico

Saint James the Apostle Church, contemporaty, Atlacomulco, Mexico

Santiago Mataindios (The Slayer Of Indians)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Santiago Mataindios, 1610, Miguel Mauricio, Temple of Tlatelolco, Mexico

Martín de Mujica, Chile's spaniard governator, represented as Santiago, (1646-1649), 1646, Alonso de Ovalle, Chile

Allegory Of Santiago In The History Of Chile (1646-1649), ?, Alonso de Ovalle, Chile

Santiago Mataindios, 1690-1720, Cuzco School, Peru

Santiago Mataindios, 18th century, Peru

Oftentimes, the enemies Santiago was slaying were not moors, but native Americans. In fact, he was seen as the protector of Spaniards from the indigenous peoples of the Americas, and, occasionally, he was depicted as a conquistador. His divinity was seen as a rival force to the indigenous gods. The appearances of the holy warrior (14 such appearances were documented) helping the Spanish troops defeat the pagan enemies and legitimize, politically and religiously, the conquest of America as a crusade. This earned the Saint other titles: Santiago Mataindios and Santiago Mataincas.

There were a few indigenous peoples who saw in the Spanish some ideal allies to fight against other indigenous peoples who were their traditional enemies and had them subdued. Thus, some native Americans have voluntarily adopted the cult of Santiago Mataindios.

Santiago mataespañoles The Protector Of Indians

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Santiago the Spaniard-Slayer, mid 19th century or 17th century, Cuzco, Peru

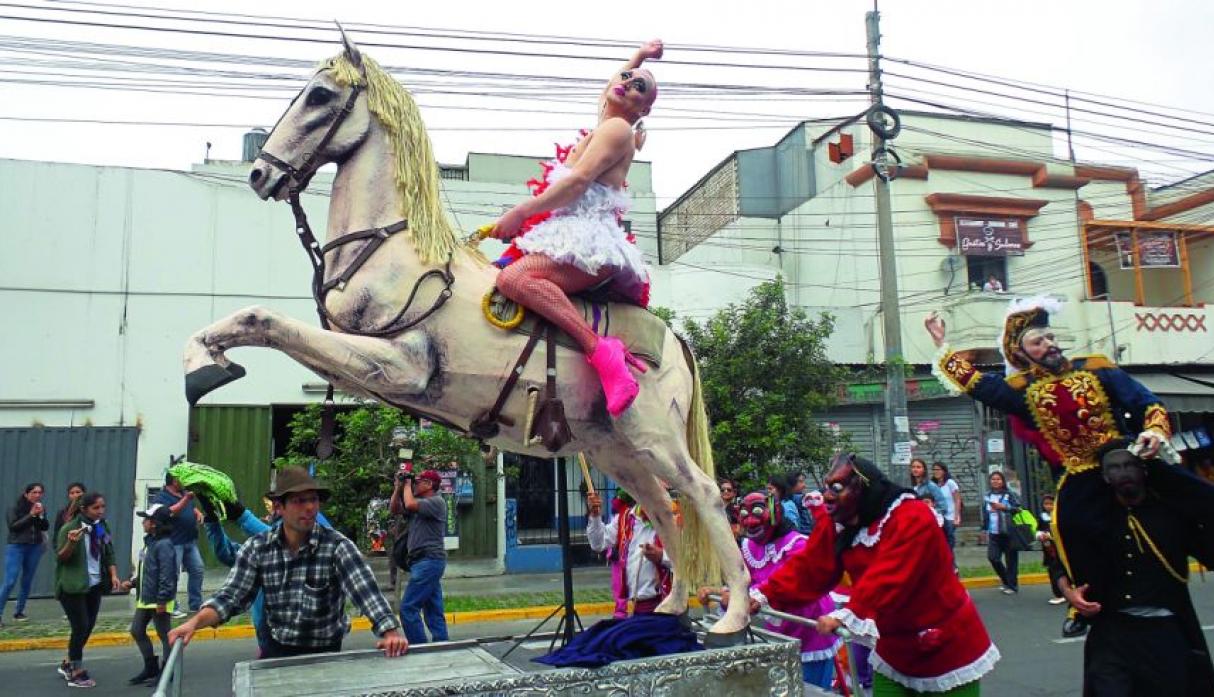

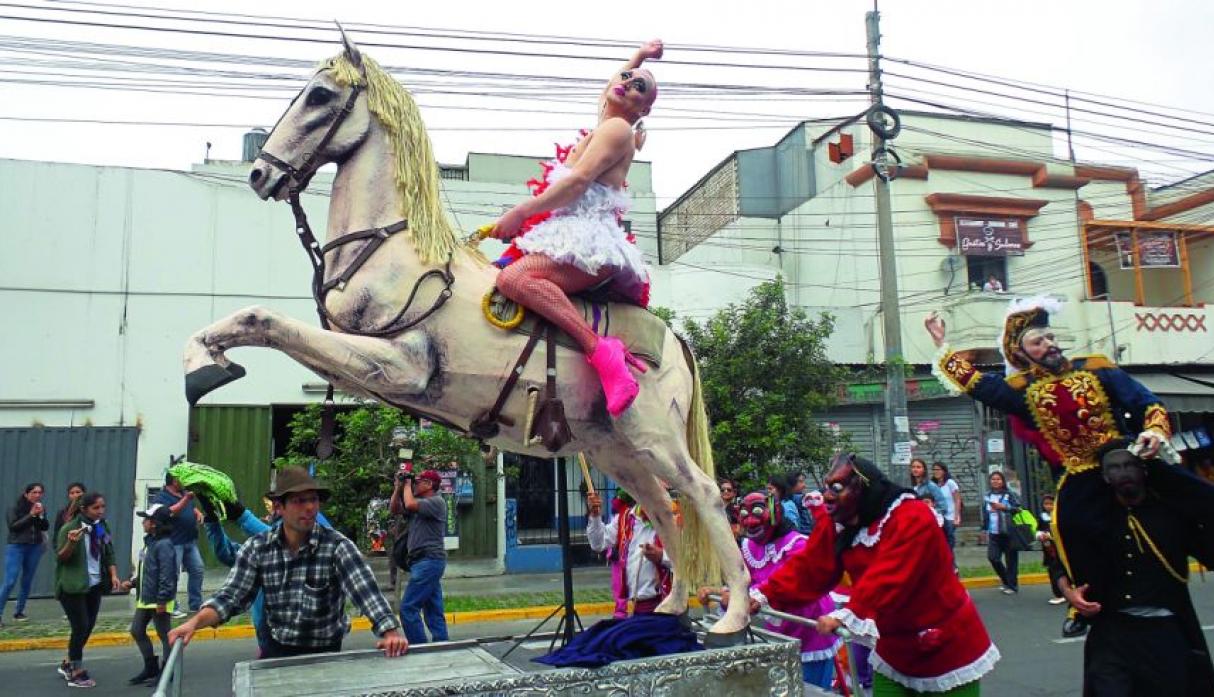

Demonstration calling to increase the budget of the culture sector, October 2017, Lima, Peru

It was

suggested that syncretic connection between Santiago and the Andean god

Yllapa (was a very popular weather god) motivated this odd veneration.

An example of this very rare iconography is found in this small silver sculpture, also originally from Cuzco, which is preserved in the Pilgrimage Museum of Santiago de Compostela. It is dated in the second third of the nineteenth century and shows the Saint the Peruvians protecting against Spanish colonizers. Recently, Peruvian artists have used Santiago’s iconography during the demonstration calling to increase the budget of the culture sector, presumably as the protector of Peruvian liberal arts!

Flemish Artists, 17th century: Flamboyant Baroque

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

What is “Flemish”?

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Map of Flandres (Spanish Netherlands), cr. 1700

Map of Flandres, Belgium, 2019

The

Spanish Netherlands was the collective name of States of the Holy Roman Empire in the Low Countries that were part of Spanish Empire from 1556 to 1714. Geographically, the Spanish Netherlands roughly corresponds to the modern Flandres, a region in Belgium. By convention, the painters that are associated with Spanish Netherlands are collectively known as the

Flemish painting school.

Horsemen’s Portraits By Peter Paul Rubens (1577 – 1640) And Anthony van Dyck (1599 – 1641)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

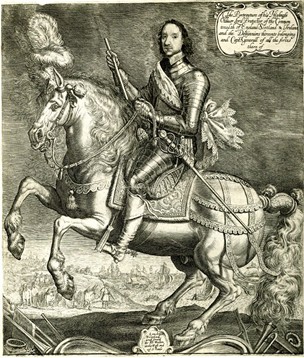

Flemish painting of 17th century was dominated by two artists: Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck. Both have painted male equestrian portraits featuring rearing horses and have their versions of Saint George. They both use large brushstrokes, which makes their paintings very dynamic.

It is interesting to observe that, despite many differences, all gentlemen on Rubens’s and van Dyck’s horsemen portraits wear the same costume (an armour with a red scarf) and they all hold a baton.

Equestrian Portrait of Giancarlo Doria, 1606, Peter Paul Rubens

St George Fighting the Dragon, 1606-10, Peter Paul Rubens

Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Buckingham, 1625, Peter Paul Rubens

The Cardinal-Infante Don Fernando de Austria at the Battle of Nördlingen, 1634-5, Peter Paul Rubens

Equestrian portrait of Prince Tomaso of Savoy-Carignan, son of Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, 1634-5, Anthony van Dyck

St George and the Dragon, before 1641, Anthony van Dyck

The Duke of Arenberg, before 1641, Anthony van Dyck

Equestrian portrait of the Duke of Arenberg (after Anthony van Dyck), 1742-88, Thomas Gainsborough, England

Horsemen’s Portraits By Gonzales Coques (1614 – 1684)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Fashions change with time. Equestrian portraits by Gonzales Coques, a minor Flemish painter of the 17th century, nicknamed de kleine van Dyck (the little van Dyck), allow to trace the evolution of the iconography of a horseman on a rearing horse in the 17th century very clearly. It starts off with traditional iconography, as used by Rubens: armour, red sash and a baton. Next, the red sash becomes blue. Then, the armour is replaced by a regular contemporary costume, and the baton transforms into a whip. Finally, the ladies appear; this is no longer a war hero portrait, but a courtly scene!

Another interesting detail that unites these paintings is that these oil paintings are not on wood or canvas, but on copper, which is unusual.

Equestrian portrait of a prince in armour, with the Order of the Golden Fleece, before 1684, Gonzales Coques

Equestrian portrait of Louis II de Bourbon, the Grand Condé, as a boy, 1643-7, Gonzales Coques

An equestrian portrait, before 1684, Gonzales Coques (style of)

Equestrian portrait of an elegant gentleman and lady in a wooded landscape, second half of the 17th century, Gonzales Coques

Equestrian portrait of an elegant couple, second half of the 17th century, Gonzales Coques

Rubens’s Huntsmen

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

There was another series of the horsemen on rearing horses, also by Peter Paul Rubens. These horsemen were depicted in the hunting scenes. It is possible that the dynamic iconography of these paintings was inspired by Leonardo da Vinci's 'The Battle of Anghiari', and that it was referencing the antique depictions of the lion hunt.

Copy of the lost Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci, 1504-5, circa 1603, Peter Paul Rubens

Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, 1615, Peter Paul Rubens

Wolf and Fox Hunt, cr. 1616, Peter Paul Rubens

Tiger Hunt, 1617-8, Peter Paul Rubens

Lion Hunt, cr. 1621, Peter Paul Rubens

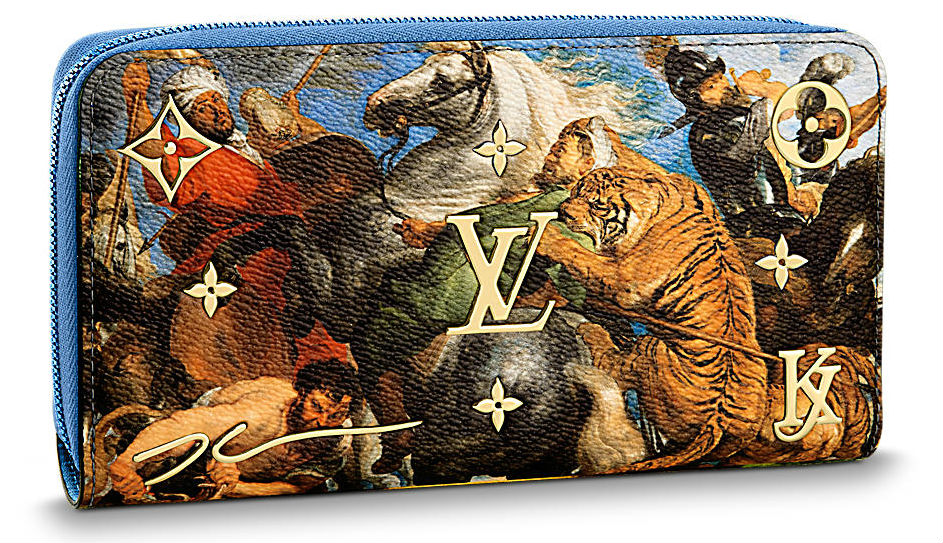

Zippy wallet with the reproduction of 'Tiger Hunt', 2017, $1770, LOUIS VUITTON

Battle Scenes (Flemish And Italian Schools)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Portrait of Sebastiaan Vrancx, 1615-41, Anthony van Dyck, Flemish

Portrait of Peeter Snayers, cr. 1626, Peter Paul Rubens, Flemish

The genre of battle scenes was pioneered in Netherlandish painting by

Sebastiaen Vrancx (1573-1647). His experience as an officer and captain of the Antwerp civil militia may have played a role in his interest in developing this genre. Approximately half of his known works are devoted to military scenes. He collaborated with

Jan Brueghel the Elder, was portrayed by

Anthony van Dyck, was a teacher of

Peter Snayers, who, in his turn, was portrayed by

Peter Paul Rubens! All these artists knew each other through

Guild of Romanists, a prestigious society which was active in Antwerp from the late 16th to the late 18th century they belonged to.

It was a condition of membership to have visited Rome; it appears to have been strictly enforced. This illustrates the importance of Italian art for Flemish artists and explains some similarities of composition, technique and colour palette. The cultural exchange was facilitated by the fact that both the Southern Netherlands and Italy belonged to the same country, the Spanish empire.

Many of Flemish horsemen’s portraits and battle scenes relate to the battles where the Catholics have crashed the Protestants. Baroque style, which was nurtured by the Roman Catholic Church as, essentially, a tool of propaganda against Protestantism, was very fitting to glorify the victory in this battle.

The Battle of Issus or Arbela, 1602, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Flemish school

The Battle of Issus or Arbela (zoom on Alexander the Great), 1602, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Flemish school

Assault on a Convoy, cr. 1612, Jan Brueghel the Elder and Sebastiaen Vrancx, Flemish

The battle of Leckerbeetje, cr. 1600-47, Sebastiaen Vrancx, Flemish

Cavalry engagement at the foot of a hill, cr. 1601-15, Sebastiaen Vrancx, Flemish

Looting of a village, possibly Wommelgem in 1589, cr. 1600-1650, Sebastiaen Vrancx, Flemish

Battle between Turkish and Christian horsemen, cr. 1610-1675, Vincent Adriaenssen, Flemish/Italian

Cavalry battle scene, cr. 1610-1675, Vincent Adriaenssen, Flemish/Italian

Cavalry battle between Turkishs and Christians, cr. 1610-1675, Vincent Adriaenssen, Flemish/Italian

The death of Decius Mus in the battle, 1618, Peter Paul Rubens, Flandres

Battle of White Mountain, 1620, Peter Snayers, Flemish

Henri IV at the battle of Ivry, 1624-6, Peter Paul Rubens and Peter Snayers, Flemish

Isabel Clara Eugenia on the Breda Site, cr. 1628, Peter Snayers, Flemish

Cavalry Skirmish, cr.1610-41, Peter Snayers, Flemish

Relief from Constance Square, 1634, Vincenzo Carducci, Italian

The Battle of Nördlingen, 1634-5, Jan van den Hoecke, Flemish

Battle of Nördlingen, 1615-55, Cornelis Schut

Frederik Hendrik and Maurits as generals, with the Battle of Flanders in the distance, 1650, Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert, Flemish

Dutch Republic, 17th century

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

After mentioning the Spanish Netherlands, we should mention the Dutch Republic, founded in 1581 by several Dutch provinces — fully seceded from Spanish rule in 1648 — that existed until the Batavian Revolution of 1795.

There were very few horsemen on the rearing horses created in the Dutch republic after 1648. This is expected; the Dutchmen were favouring the still life, genre and urban portraits to differentiate their art from the Catholic art. The source of their prosperity was trade and science, not war.

Prince Maurice of Orange during the Battle of Nieuwpoort (1600), cr. 1620-60, Henri Ambrosius Pacx, Dutch

The Princes of Orange and their Families on Horseback, Riding Out from The Buitenhof, The Hague, 1621-2, Pauwels van Hillegaert, Dutch

The disbanding of the 'waardgelders' by Prince Maurits in Utrecht, 1618, 1625, Joost Cornelisz Droochsloot, Dutch

Prince Frederik Hendrik on horseback outside the fortifications of 's-Hertogenbosch, 1632-5, Pauwels van Hillegaert, Dutch

Princes Maurits and Frederik Hendrik on horseback, 1630-5, Pauwels van Hillegaert, Dutch

The bear hunt, 1649, Paulus Potter, Netherlands

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, cr. 1650, Johannes Lingelbach, Dutch school

Diederik Tulp, 1653, Paulus Potter, Netherlands

Equestrian portrait of Johan Wolfart van Brederode, 1640-70, School of Thomas de Keyser, Netherlands

A Mughal nobleman on horseback, cr. 1656-61, Rembrandt, Netherlands

Portrait of Frederick Rihel on Horseback, 1663, Rembrandt, Netherlands

France: Bourbons, Napoleon and Aristocracy, 17th-19th centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Henry IV (1553 – 1610)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

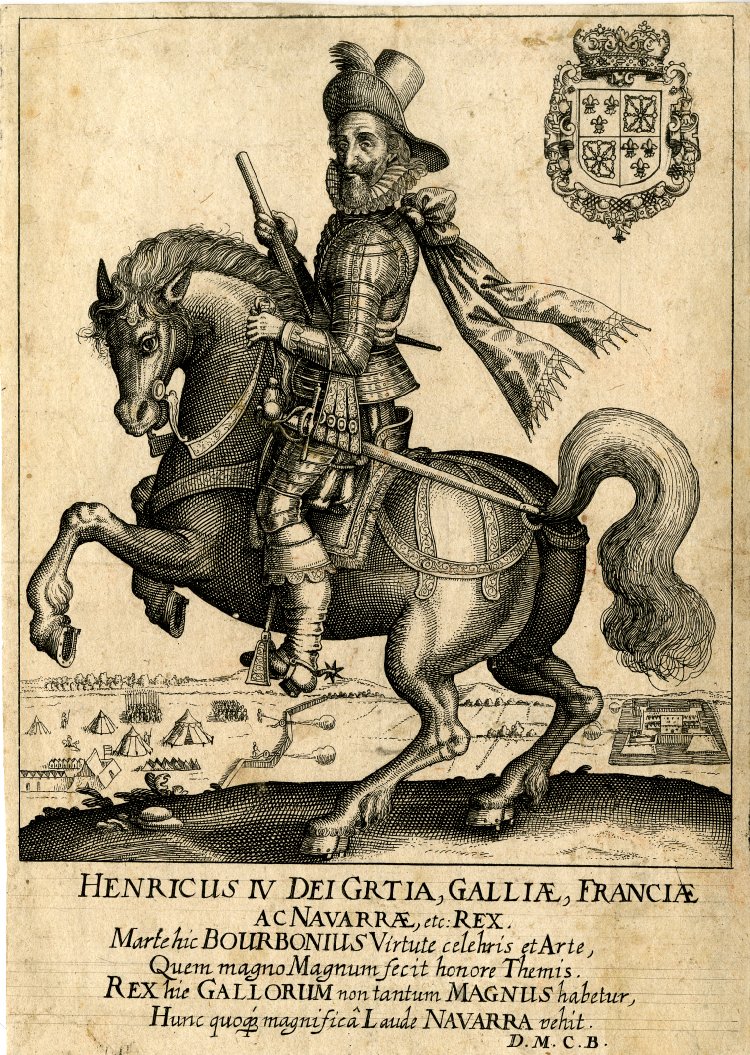

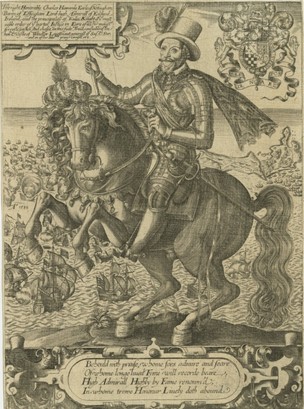

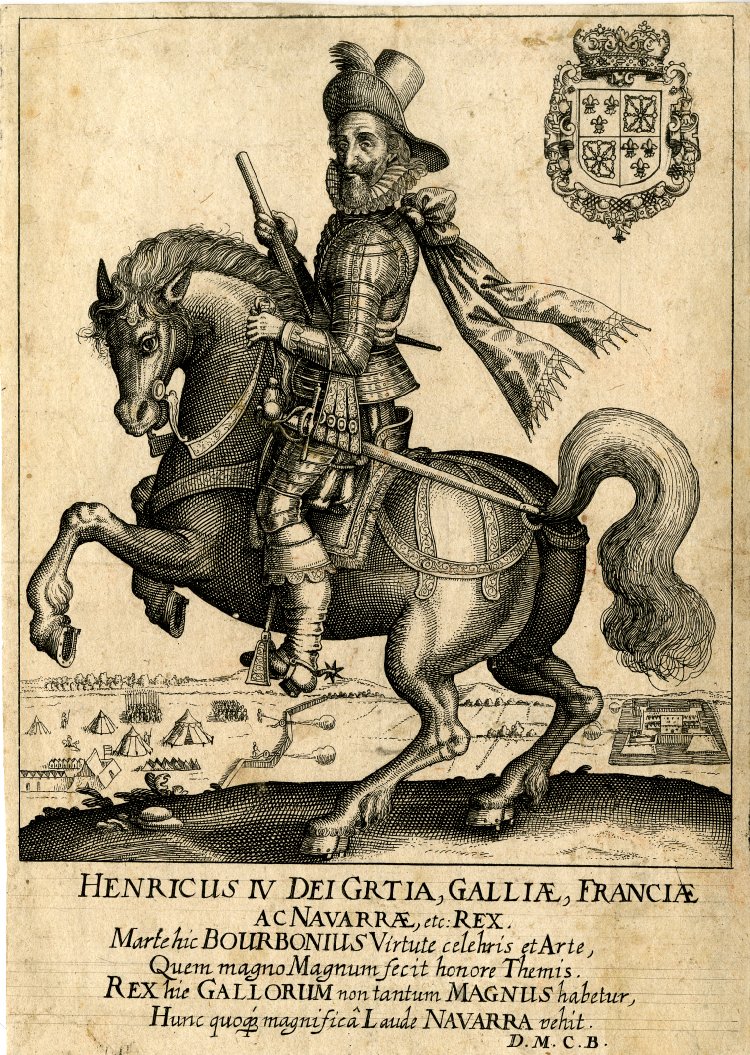

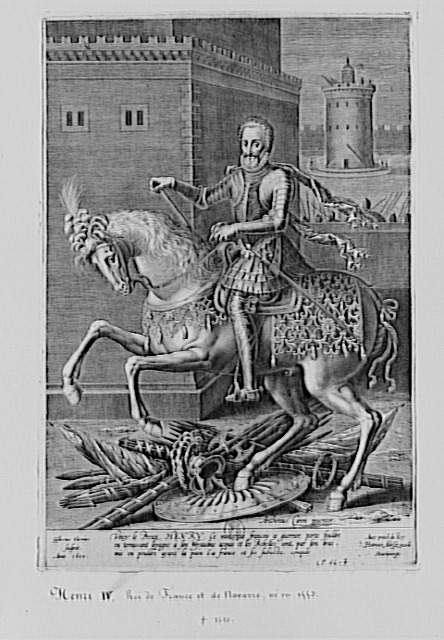

Henry IV of France, the first monarch of France from the House of Bourbon, was not the first French royal horseman on a rearing horse (Charles IX of France had been portrayed on a rearing horse), but also the first one whose images followed the standard armour-and-baton iconography.

COMPARANDUM: Charles IX, King of France, 1565-99, unknown artist

Henry IV by God's grace the king of France and Navarre aged 51 (1603), 1585-1603, Robert Boissard, France

Portrait of Henri IV, King of France, 1589-1610, ?, after Hendrick Goltzius

Henri IV at the battle of Arques, cr. 1590, ?, France

Portrait of Henri IV on horseback with Paris on the background, 1553-1610, probably after 1594, ?

Henri IV, the king of France and Navarre in 1589, 1600, ?

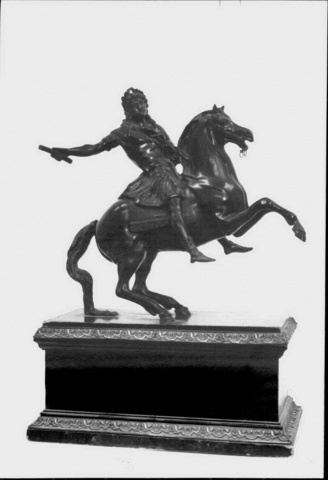

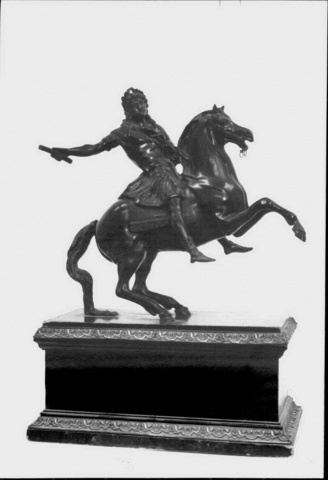

Henry IV destroying his enemies, ca. 1603, Barthélémy Prieur, France

Henri IV on horseback bringing down his enemies, cast at the beginning of the 17th century, modelled in 1600 by Barthélémy Prieur

Louis XIII (1601 – 1643)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Portraits of Louis XIII

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Few monarchs were as fond of being portraited on a rearing horse as Louis XIII and Louis XIV. This imagery well suited the apotheosis of absolute monarchy which was reached during their reign.

Louis XIII of France was depicted wearing either armour or a court costume; it seems that the only element of his appearance that would relate to antiquity is a laurel wreath. His most significant portraits were painted by Claude Deruet.

Equestrian statuette of Louis XIII, 1619-21, Pietro Tacca

Engraving of a bronze statue of Louis XIII on horseback, 1636, Nicolas Jacques, engraving made in 1765. The original bronze statue was destroyed at the Revolution (1792)

High relief of king Louis XIII on horseback, 1818, after the statue by Nicolas Jacques destroyed at the Revolution (1792)

Equestrian portrait of Louis XIII, 1635, Crispijn de Passe the Elder

Louis XIII on Horseback, cr. 1622, probably by or after a Flemish painter

Equestrian portrait of Louis XIII, 17th century, Claude Déruet (attributed to)

Louis XIII on horseback, circa 1630, Justus van Egmont

Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu in front of La Rochelle, 17th century, Unknown

Equestrian portrait of victorious Louis XIII, 17th century, Claude Déruet (attributed to)

Other Horsemen Of Claude Deruet

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Studying other Claude Deruet‘s paintings with the horsemen on rearing horses allows to see what subjects were popular at the time: mostly courtly and antique subjects.

Triumph of the Amazons, 1620s, Claude Deruet, Nancy, France

Four elements: Fire, before 1642, Claude Deruet, France

Allegory of the Peace Treaty of the Pyrenees, 1659, Claude Deruet, France

Equestrian portrait of Madame de Saint Baslemont, 1646, Claude Déruet

An equestrian portrait of a gentleman, ?, Studio of Claude Déruet

His painting of

Madame de Saint-Baslemont, made in 1646, seems to be the first portrait of a woman on a rearing horse in oil paintings.

It appears that having a portrait on a hearing horse became a status symbol. Those who could not afford the portrait made by the famous master would order a cheaper lookalike version – I believe we see an example of this in the portrait done by Claude Deruet‘s studio.

Louis XIV (1638 – 1715)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

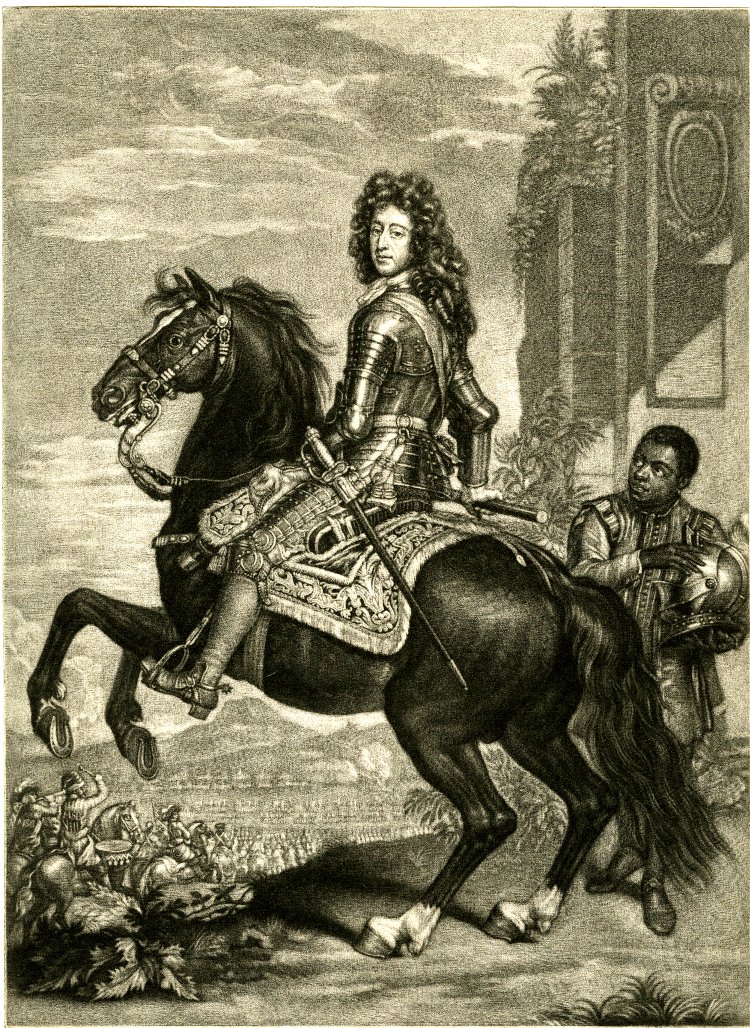

Louis XIV of France was even more fond of being depicted on a rearing horse.

Portraits of Louis XIV

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Many portraits of Louis XIV on a rearing horse were created during his reign, you can see a small selection here. Like many other aspects of his reign, these portraits reinforce his image of an infallible absolute monarch in the most visually exuberant way.

Louis XIV on horseback, 1673, Pierre Mignard

Equestrian portrait of Louis XIV of France, 17th century, Charles Le Brun and Adam Frans van der Meulen

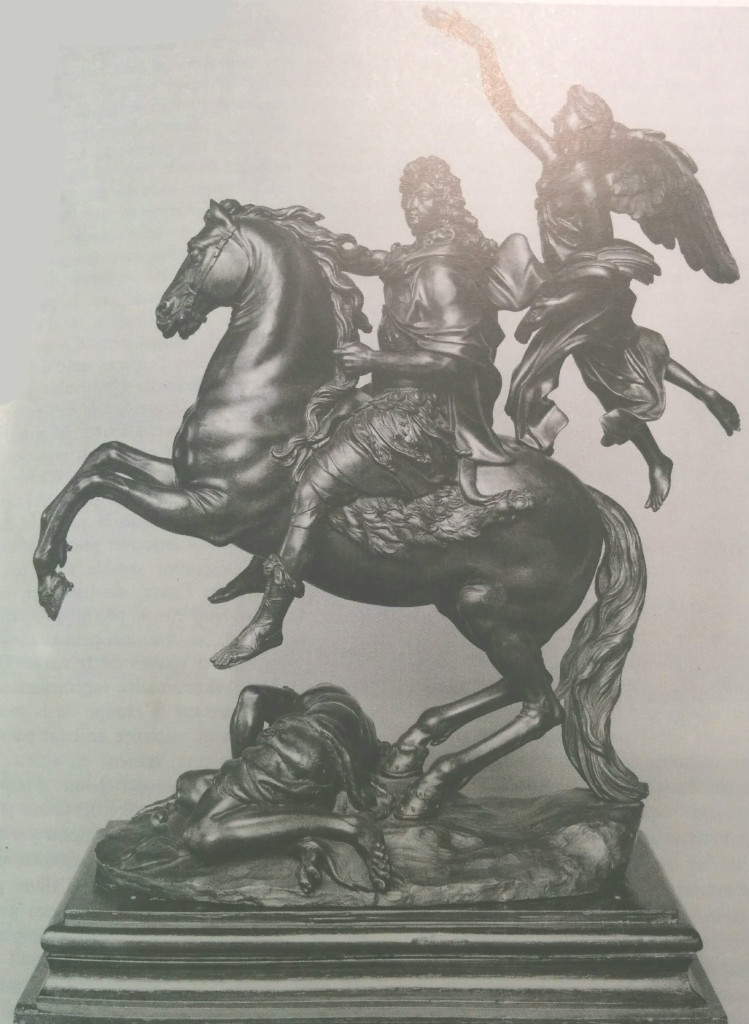

Louis XIV on horseback crowned by the Victory, 1674, Pierre Mignard

Apotheosis de Louis XIV, 1677, Charles Le Brun

Portrait of King Louis XIV during the War of Devolution, 1668, Charles Le Brun

Portraits of The Ladies of Louis XIV’s Court

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Louis XIV was known for his fondness of glamorous aristocratic ladies. The painters’ choices were in line with the preferences of the king. The most famous ladies’ portraits constitute a series of 6 paintings that were painted by Joseph Parrocel for Louis-Marie-Victor d'Aumont in the 1670s. The paintings were given as a gift to or bought by the Swedish ambassador Count Nils Bielke during his stay in Paris 1679-82. The series was later transferred to Skokloster Castle, where they are now exhibited.

Catherine de Neufville d'Harcourt-Armagnac

Anne de Souvree

Marie Isabelle Gabrielle Angelique de Lamotte-Houdancourt, the Duchess of La Ferté

Marie-Anne de Bouillon

Francoise Angelique de Lamotte-Houdancourt, the Duchess of Aumont

Francoise Madeleine Claude St. Géran

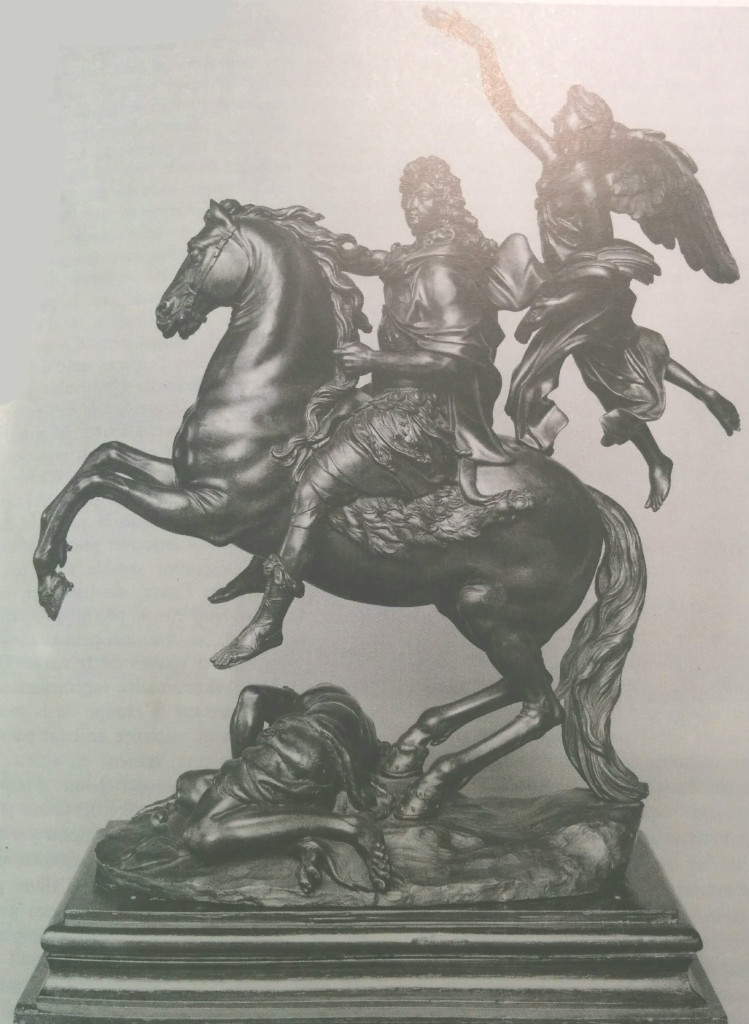

Sculptural Depictions Of Louis XIV

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

There were attempts to have a sculptural depiction of Louis XIV on a rearing horse. There exist some preparatory drawings made by Charles Le Brun and a bronze model by Le Brun’s protégé François Girardon, which, possibly, resulted in a statue that was at Place Vendôme in Paris between 1692 and 1699.

Louis XIV on horseback, cr. 1668, Charles Le Brun, France

Louis XIV on horseback, cr. 1668, Charles Le Brun, France

Louis XIV in armour trampling the vanquished, 17th century, Charles Le Brun, France

Equestrian statuette of Louis XIV, 19 century, probably after Francois Girardon (before 1692), France

Triumph of Louis XIV, Salon of War, Versailles palace, c.1678-87, Antoine Coysevox

However, Gian Lorenzo Bernini‘s creation seems to be the only large-scale statue of Louis XIV on a rearing horse created in the 17th century. Louis XIV wanted Bernini to create a freestanding marble statue similar to The Vision of Constantine. For the technical reasons, a freestanding marble statue could not have only two supporting points; so the artist has chosen to support the horse’s belly, too. The statue greatly displeased Louis XIV and was banished to the farthest corner of Versailles park.

Observe that both Girardon’s and Bernini’s statues feature the outstretched towards the back arm. This looks somewhat unnatural but is useful to balance the statue. We have seen it only once before, on Leonardo’s drawing. It would be interesting to know if Louis XIV’s sculptors have come up with the same idea independently or not.

COMPARANDUM: The Vision of Constantine, 1670, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Scala Regia, Vatican

COMPARANDUM: Corpus Christi Procession with Pope Gregory XVI in the Vatican (with The Vision of Constantine on the background), 1840, Ferdinando Cavalleri

COMPARANDUM: Constantine the Great Beholds the Sign of the Cross, second half of the 17th century, Gian Lorenzo Bernini or a later sculptor

Statue of King Louis XIV, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1665-84, Versailles

I have found three more bronze figurines of Louis XIV on a rearing horse. Two made by

Martin Desjardins were models for a public monument in

Aix-en-Provence, but, mostly because of financial difficulties, it was never completed. The other one, by

Thomas Gobert, was probably a model for the public monument in the garden of Rueil commissioned by

Armand-Jean de Vignerot du Plessis,

Duke of Richelieu, in 1685; again, it appears to not to be completed. There is also a relief depicting the king on a rearing horse made by Martin Desjardins (the statue was decorating the

Place des Victoires statue of Louis XIV that was destroyed during the French Revolution).

Louis XIV on horseback dressed à la française, after a model commissioned in 1685 (?), Gobert Thomas

Equestrian group with Louis XIV, cr. 1690-4, Martin Desjardins (or his assistants)

Louis XIV dressed à la romaine on a rearing horse, cr. 1690, Martin Desjardins

Crossing the Rhine, 16 June 1672, 1681-1685, Martin Desjardins

Victory crowning a Prince, probably Louis XIV, early 18th century, Guillielmus de Grof, Bavaria

The projects of the monuments of Louis XIV on a rearing horse have failed. However, the idea was much admired by other European rulers, and the influence of French sculptural school was far-reaching. British and Bavarian sovereigns have commissioned the monuments similar to Desjardin’s model.

Guillielmus de Grof seemed to have made similar sculptures of both Louis XIV (on the right) and Bavarian elector Maximilian II Emanuel. Landmark equestrian statues in Dresden and Saint-Petersburg were made by French court sculptors. Swedish monarch went as far as buying plaster casts of French equestrian statues… You can read more about it in the corresponding sections of this work.

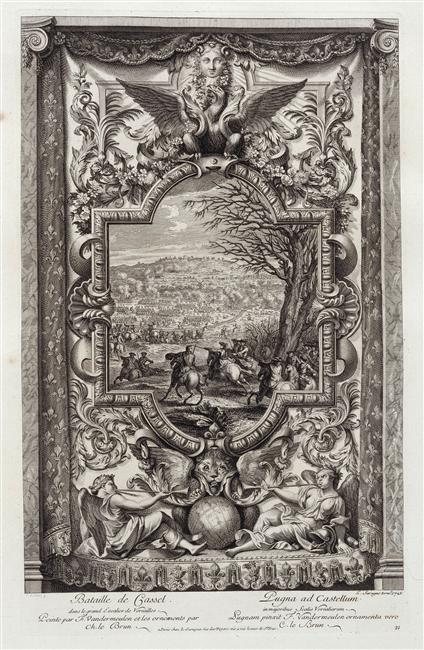

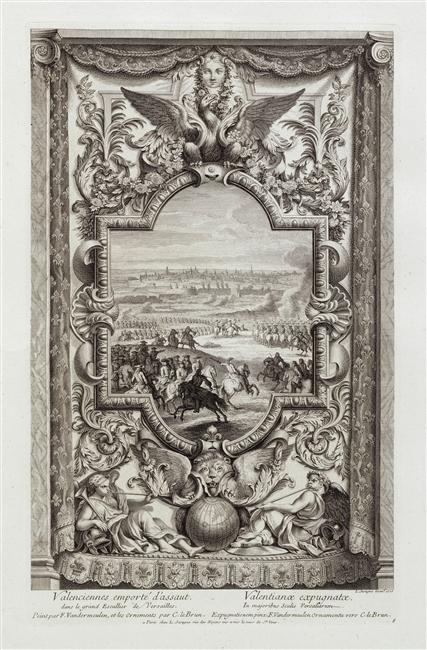

Other works by Charles Le Brun (1619 – 1690)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Charles Le Brun was the leading artist at the court of Louis XIV, who declared him “the greatest French artist of all time”. As we can see that, other than the portrayals of the king, he was using the horsemen to depict the battles of antiquity, such as the battles of Alexander the Great and the Battle. Next, there are three scenes from Franco-Dutch War (1672 – 1678) won by France. Lastly, there is a depiction of The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple painted in accordance with the icongraphy defined by Raphael.

Battle of the Granicus, 1665, Charles Le Brun, Paris, France

The Battle of Arbela, 1669, Charles Le Brun

Alexander and Porus, 1665, Charles Le Brun, Paris, France

Expulsion Of Heliodorus, before 1690, Charles Le Brun, Paris, France

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, 1666, Gérard Audran after Charles Le Brun, France

Battle of Saint-Omer, 1720, Louis Surugue after Van der Meulen and Charles Le Brun, Paris, France

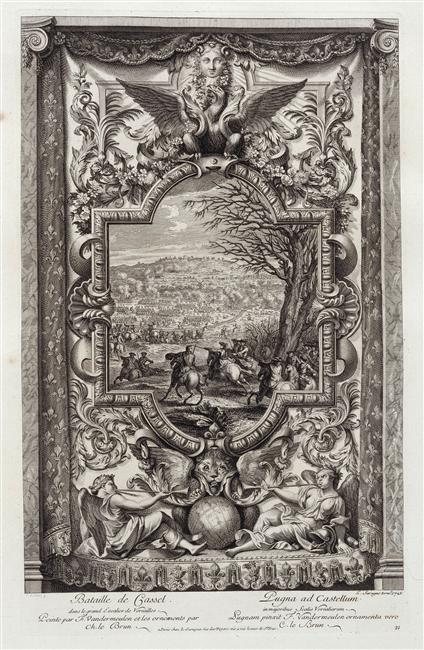

Battle of Cassel, 1720, Louis Surugue after Van der Meulen and Charles Le Brun, Paris, France

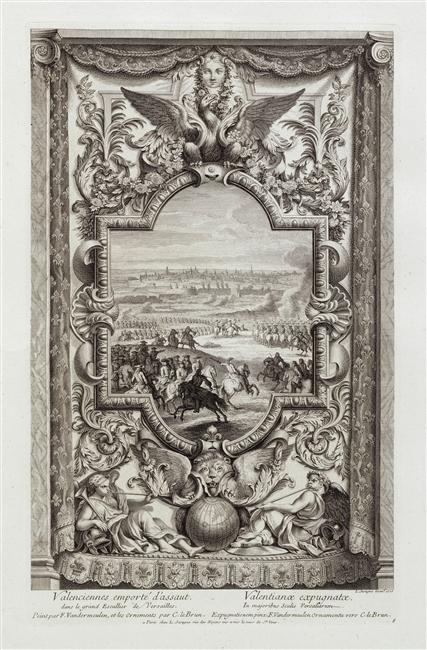

Regaining Valenciennes, 1720, Louis Surugue after Van der Meulen and Charles Le Brun, Paris, France

Louis XV (1710 – 1774), Louis XVI (1754 – 1793) And Their Wives

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Presumably, Frenchmen have grown weary of the image of a rider on a rearing horse, so we do not see much of it during Louis XV reign: below is one engraving that depicts Louis XV and one painting, which shows his wife Marie Leszczyńska. Then we have two paintings of Marie Antoinette on a rearing horse, and only one painting of her husband, Louis XVI, which was made after the revolution (observe the Tricolor cockade) and, unlike the similar portraits of his ancestors, the soon to be decapitated king does not look confident at all.

Equestrian portrait of Louis XV, 1765, altered version of an engraving made in 1732, print made by Louis Jacques Cathelin after Noël Le Mire (Louis XV's face) and Charles Parrocel

Portrait of Marie Leczinska in front of the palace of Fontainebleau, 1725, Jean-Baptiste Martin

Equestrian portrait of the queen Marie-Antoinette, 1783, Louis-Auguste Brun

Marie-Antoinette hunting, 1783, Louis-Auguste Brun

Louis XVI as a citizen-king, sporting the tricolour cockade on his hat, 1791, Jean Baptiste François Carteaux

Horsemen’s Portraits At The Time of Napoleon I (1769 – 1821)

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The ascension of Napoleon has revived the image of the horseman on the rearing horse. Further similar portraits have appeared; their subjects are no longer royalties, but the aristocratic men who wish to boast of their horsemanship skills.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1802, Jacques-Louis David

Portrait of Jérôme Bonaparte, cr. 1808, Antoine-Jean Gros

Equestrian portrait of prince Boris Yusupov, 1809, Antoine-Jean Gros

Equestrian portrait of Joachim Murat, 1812, Antoine-Jean Gros

An Officer of the Imperial Horse Guards Charging, 1812, Jean Louis Théodore Géricault

Louis XIV On A Rearing Horse At The Place De Victoires, 1816–1828

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Statue of Louis XIV, 1816–1828, Paris

Statue of Louis XIV, (a close-up)

Finally, after the demise of Napoleon, during

Bourbon Restoration Louis XIV has got his statue on a rearing horse that will survive the turmoils and is still with us today: you can see it in Paris, on

Place des Victoires.

This appears to be the last public statue where the horseman is dressed à l’antique and has a baton.

Given Louis XIV fondness of being represented on a rearing horse, one could not find a better person to conclude the sub-series of antique-themed horsemen.

Galerie des Batailles, Palace of Versailles, 1830s

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Louis-Philippe Opening the Galerie des Batailles (1837), 1837, François Joseph Heim, Versailles, France

The

Galerie des Batailles (Gallery of Battles) is a gallery occupying the first floor of the Palace of Versailles. 120 metres long and 13 metres wide, it is similar to the grand gallery of the Louvre and was intended to glorify French military history from the

Battle of Tolbiac (cr. 496) to the

Battle of Wagram (1809).

Its creation was the idea of Louis-Philippe I, who opened in in 1837.

Battle of Mons-en-Pévèle (1304), cr. 1839, Charles-Philippe Larivière, Galerie des Batailles, Versailles, France

Battle of Rocroi (1643), cr. 1834, François Joseph Heim, Galerie des Batailles, Versailles, France

Battle of Lens (1648), cr. 1835, Pierre Franque, Galerie des Batailles, Versailles, France

Battle of the Dunes at the siege of Dunkirk (1658), 1837, Charles-Philippe Larivière, Galerie des Batailles, Versailles, France

Battle of Villaviciosa (1710), 1836, Jean Alaux, Galerie des Batailles, Versailles, France

Battle of Fleurus (1794), 1837, Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse, Galerie des Batailles, Versailles, France

Battle of Jena (1806), 1836, Horace Vernet, Galerie des Batailles, Versailles, France

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863): Huntsmen And Warriors

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Liberty Leading the People, 1830, Delacroix Eugène, France

French painter

Eugène Delacroix is perhaps best known for his painting

Liberty Leading the People. But he has also produced a large number of paintings and drawings that depict horsemen on rearing horses!

Even without checking his biography, one can clearly see that Delacroix was very much inspired by Peter Paul Rubens. The depictions of the hunt are certainly very similar in their dynamics, caught in the midst of the action. It is possible that Peter Paul Rubens was inspired by Leonardo’s The Battle of Anghiari, which Rubens copied. Their representations of Saint George are very different, however, later images of Rubens’s horsemen have a similar composition. In addition, their brushwork and colour palettes are quite similar.

Lion Hunt, 1855, Delacroix Eugène, France

COMPARANDUM: Lion Hunt, cr. 1621, Peter Paul Rubens

COMPARANDUM: Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, 1615, Peter Paul Rubens

The Tiger Hunt, 1854, Delacroix Eugène, France

COMPARANDUM: Tiger Hunt, 1617-8, Peter Paul Rubens

COMPARANDUM: Copy of the lost Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci, 1504-5, circa 1603, Peter Paul Rubens

A Persian Horseman with a Lance, cr. 1820-7, Delacroix Eugène, France

Collision of Moorish Horsemen, 1843-4, Delacroix Eugène, France

Saint George Fighting the Dragon, 1847, Delacroix Eugène, France

COMPARANDUM: St George Fighting the Dragon, 1606-10, Peter Paul Rubens

Arab Horseman Attacked by a Lion, 1849-50, Delacroix Eugène, France

Moroccan Horseman Crossing a Ford, cr. 1850, Delacroix Eugène, France

Jaguar Attacking a Horseman, cr. 1855, Delacroix Eugène, France

A Turk Surrenders to a Greek Horseman, 1856, Delacroix Eugène, France

Heliodorus Driven from the Temple, cr. 1854-61, Eugène Delacroix, Paris, France

Holy Roman Empire and Germany, 15th-20th Centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Drinking Horns, 15th-16th Centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The first drinking vessels with horsemen were in the shape of horns. Most of those I have found were linked to Holy Roman Empire.

Drinking horn belonging to Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor (detail), cr. 1400, possibly a gift from the Order of Teutonic Knights

Drinking horn belonging to Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor (detail), cr. 1400, possibly a gift from the Order of Teutonic Knights

The Griffin's claw cup showing Marcus Curtius leaping into the chasm and Lot and his daughters, 1541-1583, Hans and Lorenz Faust, Mainz, Germany

Detail of the Griffin's claw cup showing Marcus Curtius leaping into the chasm, 1541-1583, Hans and Lorenz Faust, Mainz, Germany

Silver drinking horn of the St. George or Crossbow Civic Guards, 1566, Frederik Jans, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Drinking Games And Table Centrepieces, 17th Centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

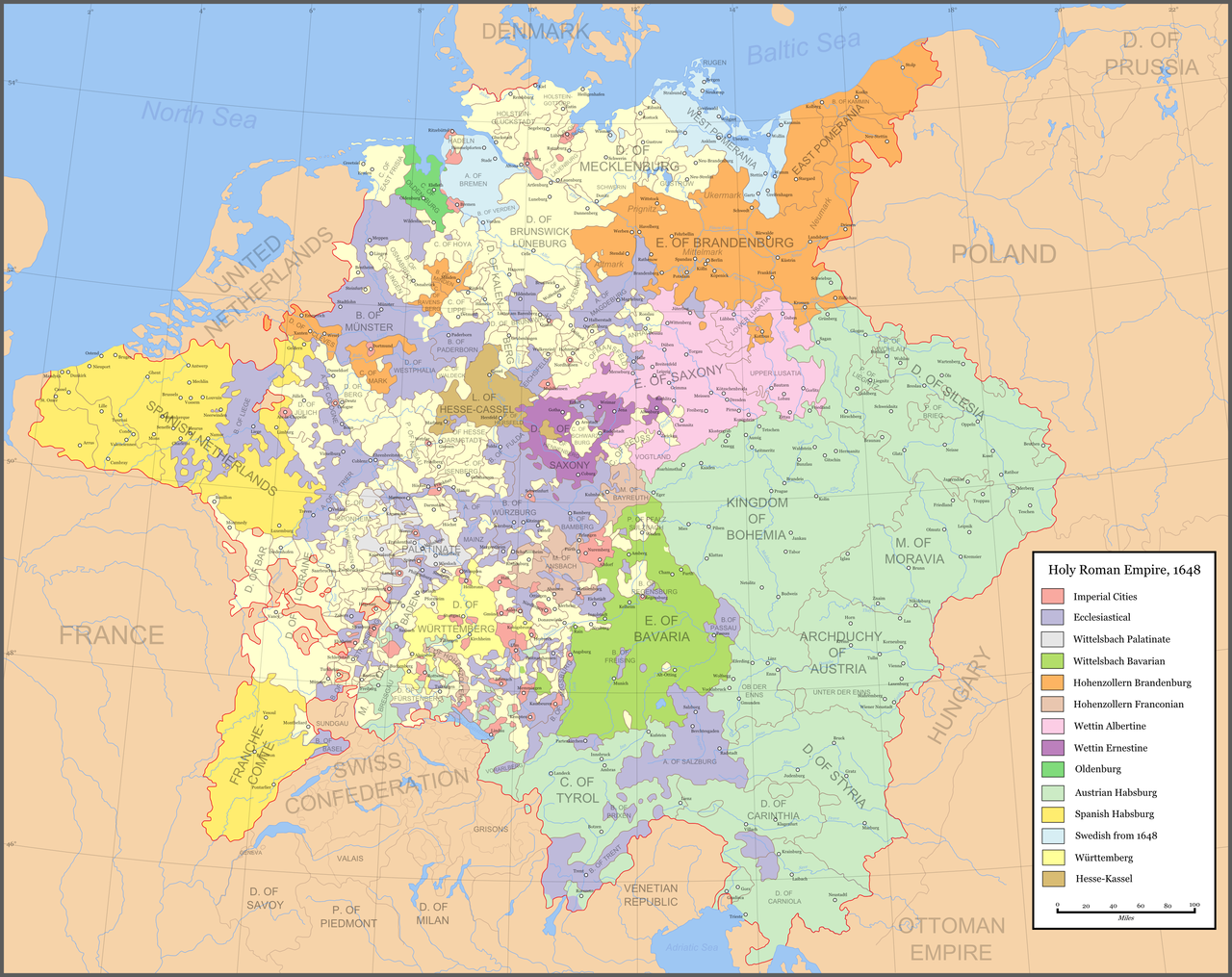

Map of the Holy Roman Empire in 1648, after the Peace of Westphalia

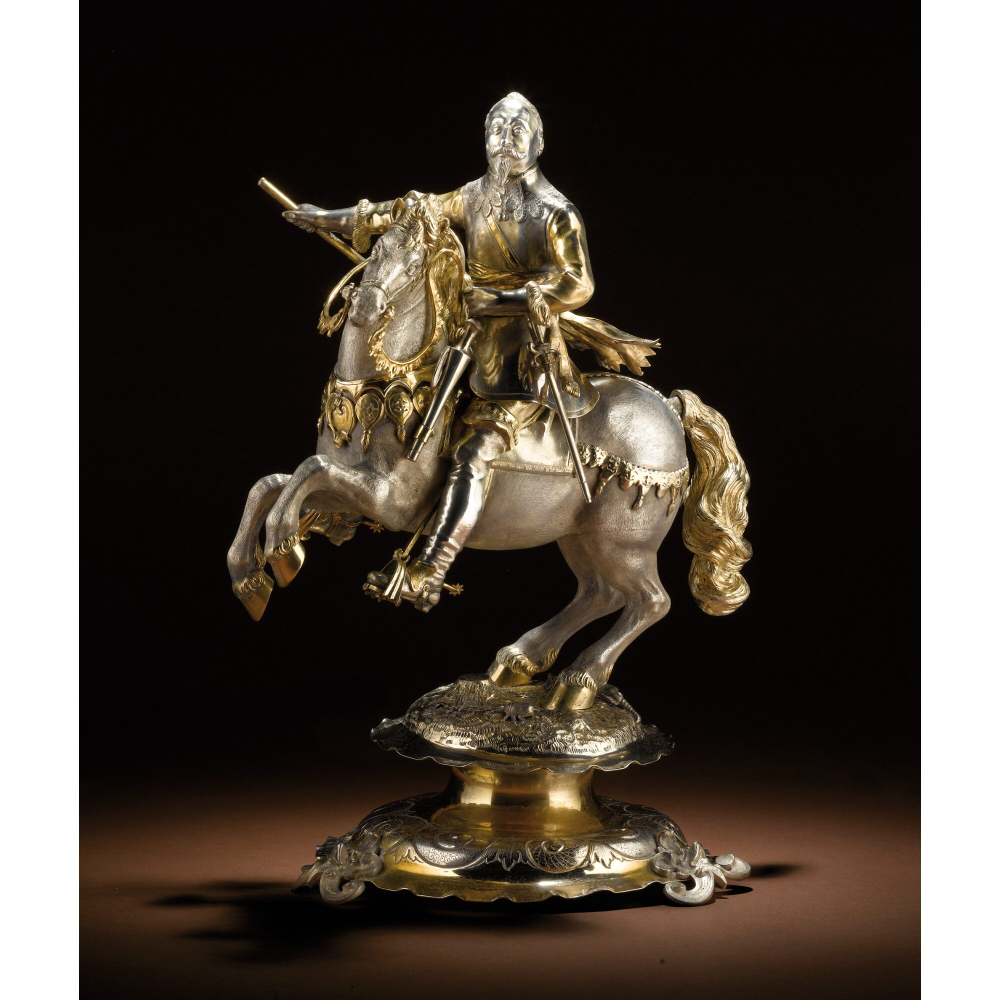

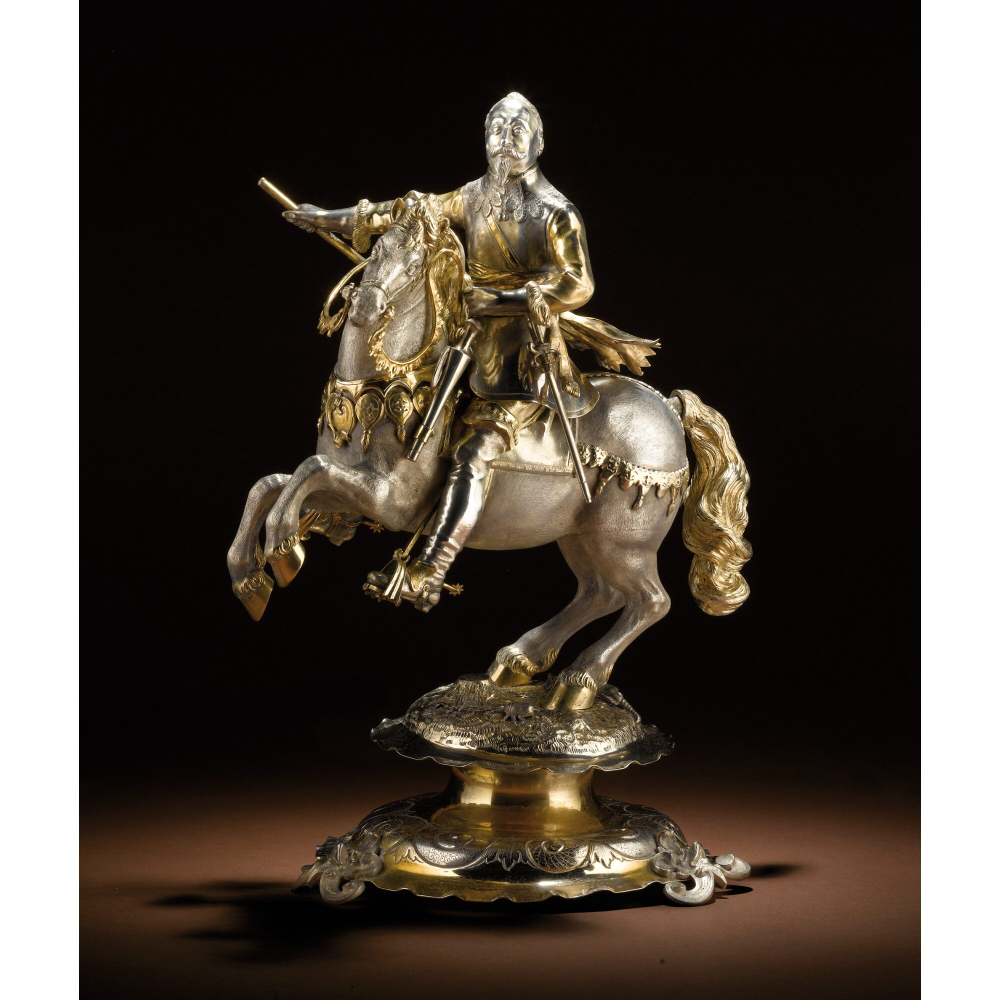

In the 17th century the drinking vessels become even more elaborate, they looked like small sculptures. The examples below are of excellent quality, they are genuine art objects, and we know the goldsmiths who made them.

Most were produced in Augsburg, one of Free Imperial Cities of Holy Roman Empire.

Automation with the figure of Saint George, cr. 1615, Jakob Miller the elder, Augsburg, Germany

Automation with the figure of Saint George, cr. 1618-1622, Joachim Fries, Augsburg, Germany

Parcel-gilt silver equestrian figure of St. George, cr. 1640, Melchior Gelb I, Augsburg, Germany

Horse and Rider, 1630, Hans Ludwig Kienle, Ulm, Germany

Equestrian statuette of Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden, 1635, Daniel Lang, Augsburg, Germany

Drinking cup/centrepiece modelled as Charles I Stuart, King of England, 1639-1649, David Schwestermüller, Augsburg, Germany

Drinking cup/centrepiece, modelled as Gustavus Adolphus II King of Sweden, 1644-1647, David Schwestermüller I, Augsburg, Germany

Table figurine 'Riding Warrior', 1665-1669, Heinrich Mannlich, Augsburg, Germany

Drinking cup/centrepiece modelled as a warrior on horseback, 1673, Mannlich Heinrich, Augsburg, Germany

Drinking cup/centrepiece modelled as a horseman, 1680-1684, Lorenz I Biller, Augsburg, Germany

Drinking cup/centrepiece modelled as mounted warrior, Second half of the 17th century, Augsburg, Germany

Some featured mechanisms that allow them to move on the table! You can see a similar mechanism in action below.

Diana and Stag Automaton:

Saxony: Gold and Porcelain, 18th – 19th Centuries

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Two German lands where the image of a horseman on a rearing horse was particularly popular were Saxony and Bavaria.

Golden Horsemen of Dresden

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Golden Horseman, 1735, Dresden, Saxony (Germany)

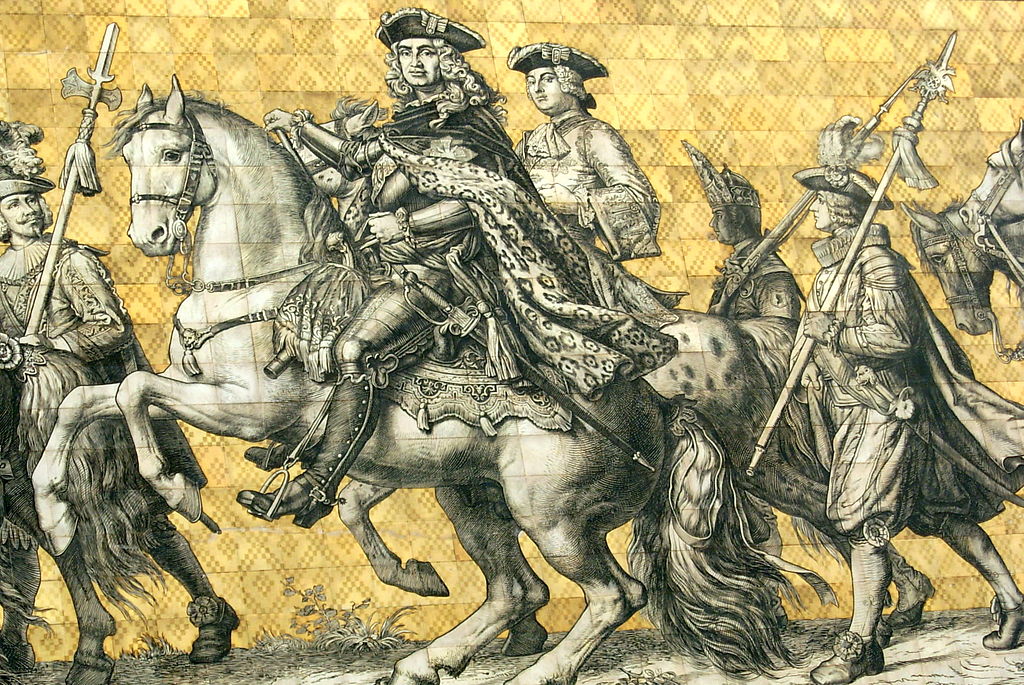

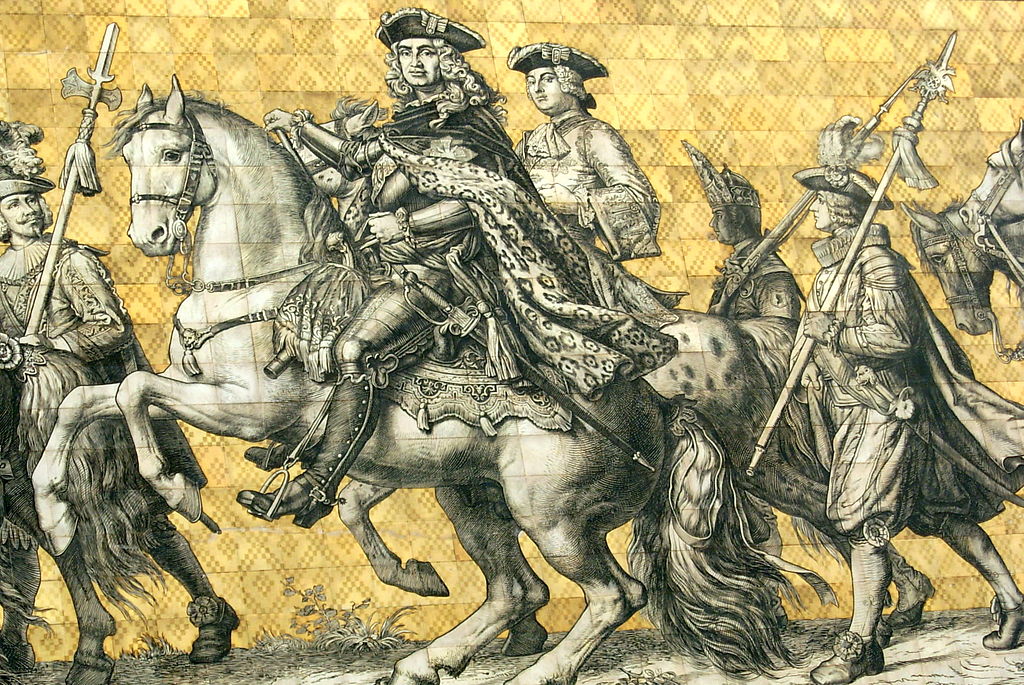

August II and August III, fragment of Fürstenzug, 1871-6 and 1904-7, Dresden, Germany

In Saxony, it was mostly associated with two sovereigns,

Augustus II the Strong (1670-1733) and

Augustus III of Poland (1696-1763), the father and the son. The most famous depiction is certainly

the Golden Horseman. The artists who have set the trend,

Louis de Silvestre and Jean-Joseph Vinanche, were both French. However, the Golden Horseman’s colour reminds us of the drinking vessels that we have seen above, which makes it part of German tradition (Ludwig Wiedemann, a smith who has cast it, came from Augsburg where many of these drinking vessels were made). See

another post for more information about the Golden Horseman. It is no surprise that

Fürstenzug, the artwork created at the end of 19 century to celebrate the anniversary of Saxon dynasty depicts two most prominent sovereigns, Augustus II and Augustus III, on horseback, on golden background – this very much follows the tradition.

Portraits Of Electors of Saxony

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

There were conventional portraits, too.

Equestrian portrait of August III, circa 1718, Louis de Silvestre

August III, 1704, Johann Christoph Oberdorffer

Equestrian portrait of August II the Strong, circa 1718, Louis de Silvestre

porcelain horsemen

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Augustus III porcelain figurine, Meissen, cr.1850

Augustus II porcelain figurine, cr. 1720

These images have inspired many porcelain horsemen, mostly done by

Meissen porcelain factory. The choice of the media was not without a reason. Augustus II has sponsored the discovery of porcelain in Europe.

Meissen porcelain factory was the first European porcelain producer. According to

the Royal Collection, the figurines representing Augustus were among the first items produced by Meissen Manufactory, and were used as diplomatic gifts (they were the equivalents of modern

selfies); it seems that the son has continued the tradition, but has also introduced the horseman on a rearing horse figurines that were influenced by the Golden Horseman.

Langeloh’s expertise of the 1745 figurine tells the story of the creation of the first porcelain Horseman.

Model for a 12m equestrian statue to Augustus III, 123cm x 94cm x 117cm

A Meissen Equestrian Figure, cr. 1745-50

Augustus III porcelain figurine, Model by Johann J. Kaendler

Augustus III porcelain figurine, Model by Johann J. Kaendler

Augustus III porcelain figurine, Model by Johann J. Kaendler

Augustus III porcelain figurine, 20th century, incised in 1796,

Bavaria, 18th Century: Possible Influence of France And Spain

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

There were quite a few depictions of horsemen on the rearing horses in Bavaria. The most depicted sovereign was Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria (1662-1726, he was also Kurfürst of the Holy Roman Empire, the last governor of the Spanish Netherlands and duke of Luxembourg). Given his political situation, we can expect that the elector’s choice of self-representation was influenced by Spain and France.

Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, ?

Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, ?

Maximilian II Emanuel, ?, Ferdinand Karl Bruni

Elector Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria on Horseback, 1707, Roger Schabol, after a model by Desjardins

Elector Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria as Victor over the Turks, 1714, Guillielmus de Grof, Bavaria

Elector Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria as Victor over the Turks (detail), 1714, Guillielmus de Grof, Bavaria

Prince Maximilian II Emmanuel of Bavaria, 1729, Giuseppe Volpini

Elector Maximilian III Josef of Bavaria on horseback, cr.1750, George Desmarées, Bavaria, Germany

Elector Karl Albrecht later Charles VII on horseback, 1758, Georges Desmarées, Bavaria, Germany

Elector Maximilian III Josef of Bavaria on horseback, 1758, Georges Desmarées, Bavaria, Germany

Historistm in the late 19th – early 20th century: Drinking Vessels

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

The Unification of Germany into a German Empire in 1871 has prompted interest in the historical heritage in general and high-quality replicas of the historical silver objects depicting horsemen on rearing horses in particular.

Production centres were mostly in Hanau (this centre specialised in historical replicas, see Hanau Silver) and Berlin.

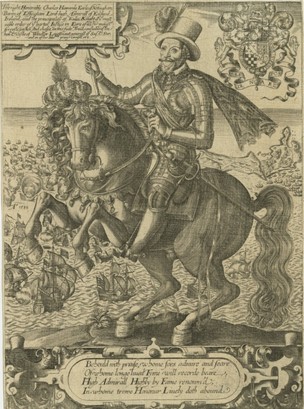

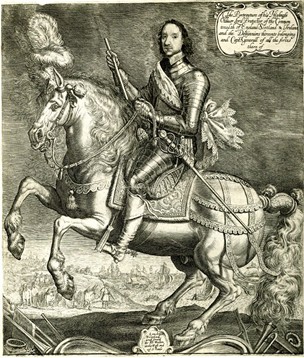

Silver tankard showing cavaliers including a marshal, probably the Stadtholder (later William III of England) (detail), cr.1830-70, Berlin (?), Germany

Silver tankard showing cavaliers including a marshal, probably the Stadtholder (later William III of England) (detail), cr.1830-70, Berlin (?), Germany

Equestrian figure of Charles I Stuart, King of England, electrotype after a 1639-1649 original, 19th century, Elkington & Co., Birmingham, United Kingdom

Drinking cup/centrepiece modelled as Gustavus Adolphus II King of Sweden, 1880, Germany

A drinking game with a figure of a horseman, cr. 1900, Neresheimer, Hanau, Germany

Silver drinking horn, cr. 1900, JD Schleissner & Söhne, Hanau, Germany

Solid silver pair of knight horseman figures, cr. 1900, Georg Roth & Co, Hanau, Germany

Solid silver large knight horseman figure, cr. 1910, Germany

Solid silver pair of knight horseman figures, cr. 1920, Germany

Austria, 17th to 19th century: Little Known Gems

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

It is interesting to see how each country was finding its unique way to interpret the theme of a horseman on a rearing horse. In the case of Austria, the feeling that I am getting when I look at their versions is lightness, giving the viewer the impression of weightlessness of the objects.

Caspar Gras, 1585 – 1674

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

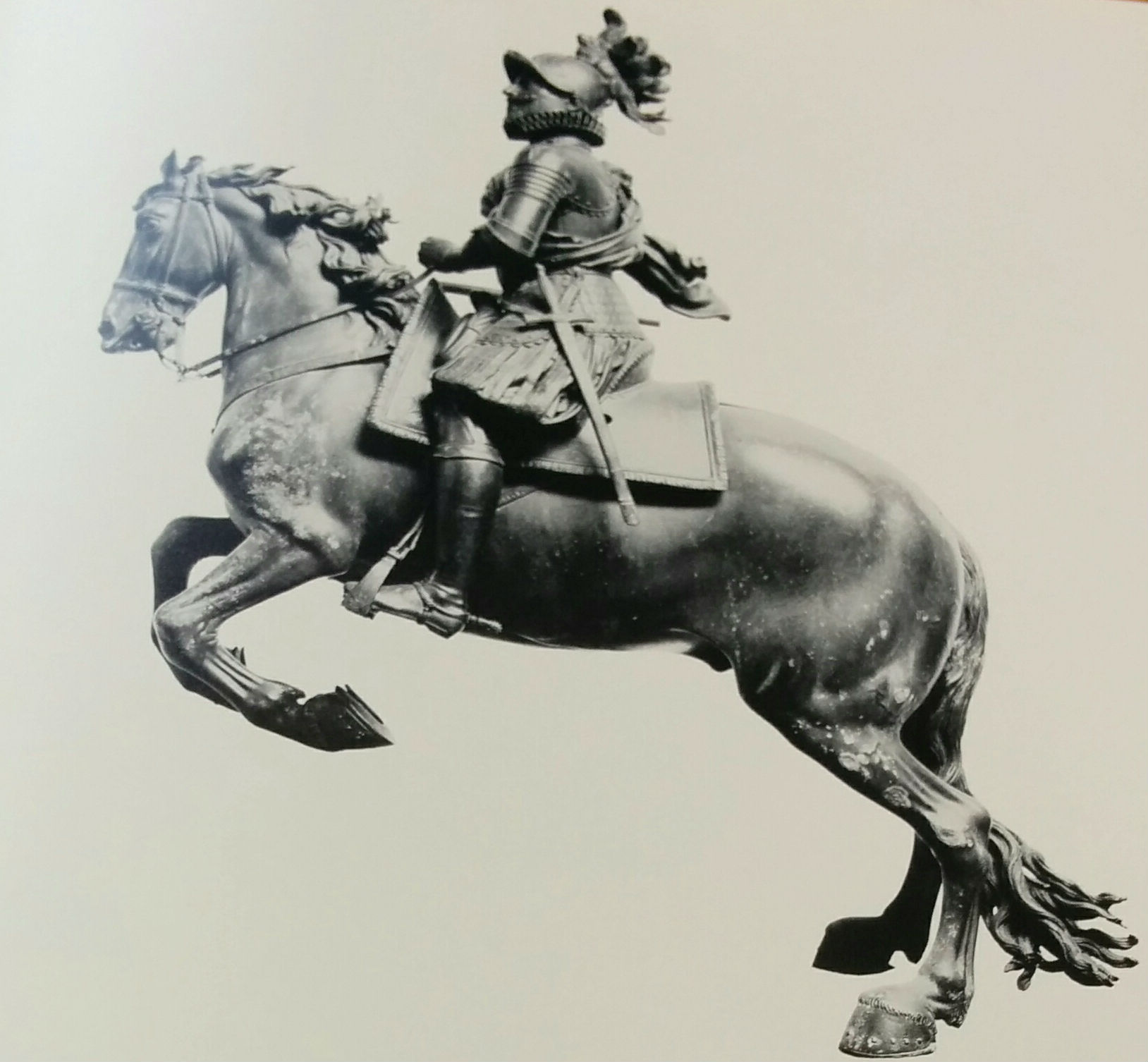

The First Large Statue With Two Support Points

↑ Back To Table Of Contents ↑

Equestrian statue of Archduke Leopold V on top of Leopoldsbrunnen, 1631, Caspar Gras, Innsbruck, Austria

Leopoldsbrunnen, photograph taken before 1941, 1623-30, Position: 1893, Innsbruck, Austria

Pegasus, 1661, Caspar Gras, Salzburg, Austria

COMPARANDUM: Monument to Philip IV, Pietro Tacca, 1634-40, Madrid

COMPARANDUM: Statue of Andrew Jackson, 1852, Clark Mills, Washington D.C., U.S.A.

Caspar Gras, a little known Austrian genius artist, was particularly good in making his statues look weightless. He created the first rearing horse monument with only two support points. According to

Charles Avery, it was the first life-size bronze horseman on a rearing horse in Europe. It appeared in Innsbruck in 1630 or 1631 or 1632 (different sources state different dates), some 220 years before the American monument to Andrew Jackson and almost 10 years before the Madrid monument three support points equestrian monument to Philip IV of Spain. It was the equestrian monument of