Horsemen With Replaceable Heads

The artists reuse the artworks that were created previously, by them or by other artists. This can be quicker or cheaper than creating fully original work.

Prints

Prints are the type of artwork where the heads can be easily replaced, and more than one version will remain.

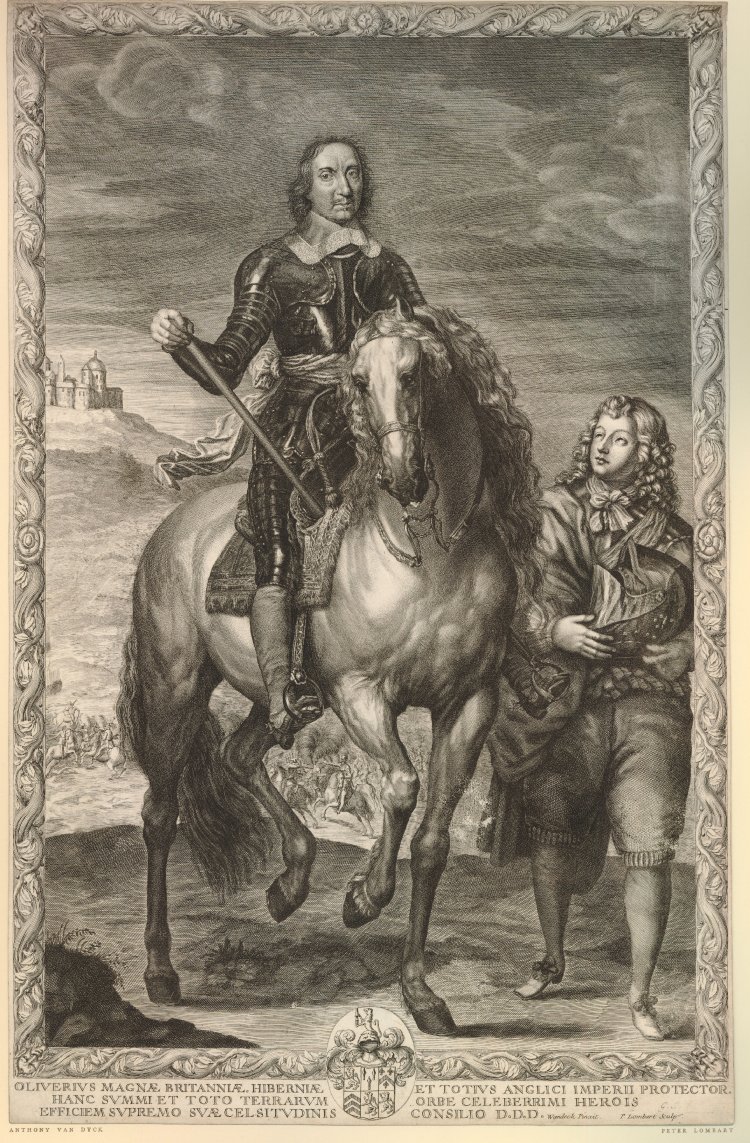

‘The Headless Horseman’

The resulting print became known as ‘The Headless Horseman’. It had undergone seven transformations:

- Oliver Cromwell;

- There is no head;

- Louis XIV;

- Louis XIV again;

- Cromwell again;

- Charles I;

- Cromwell for the third time.

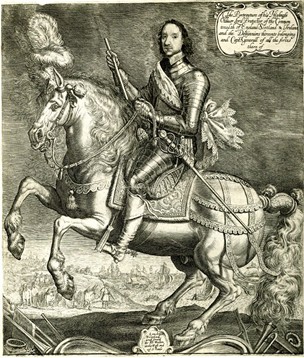

French Kings, English Aristocrats And Oliver Cromwell (Again)

The portraits of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton and Oliver Cromwell are also very similar: the heads, the inscriptions and the clothes change, and the rest of the composition remains the same.

Statues and Statuettes With New Heads, 17th Century

Statues and statuettes can get new heads, too, mostly for economic reasons.

This economical approach is considered legitimate even for self-glorification. One of the examples is the project of a statue for Charles XII of Sweden. Swedish monarch agents have purchased the plaster cast of Louis XIV; they were planning to convert it to Karl XII statue. Unfortunately, the cast was broken during the transportation, and no material evidence of that would-be statue remains.

However, some examples of the statues and statuettes that had their heads replaced are still with us.

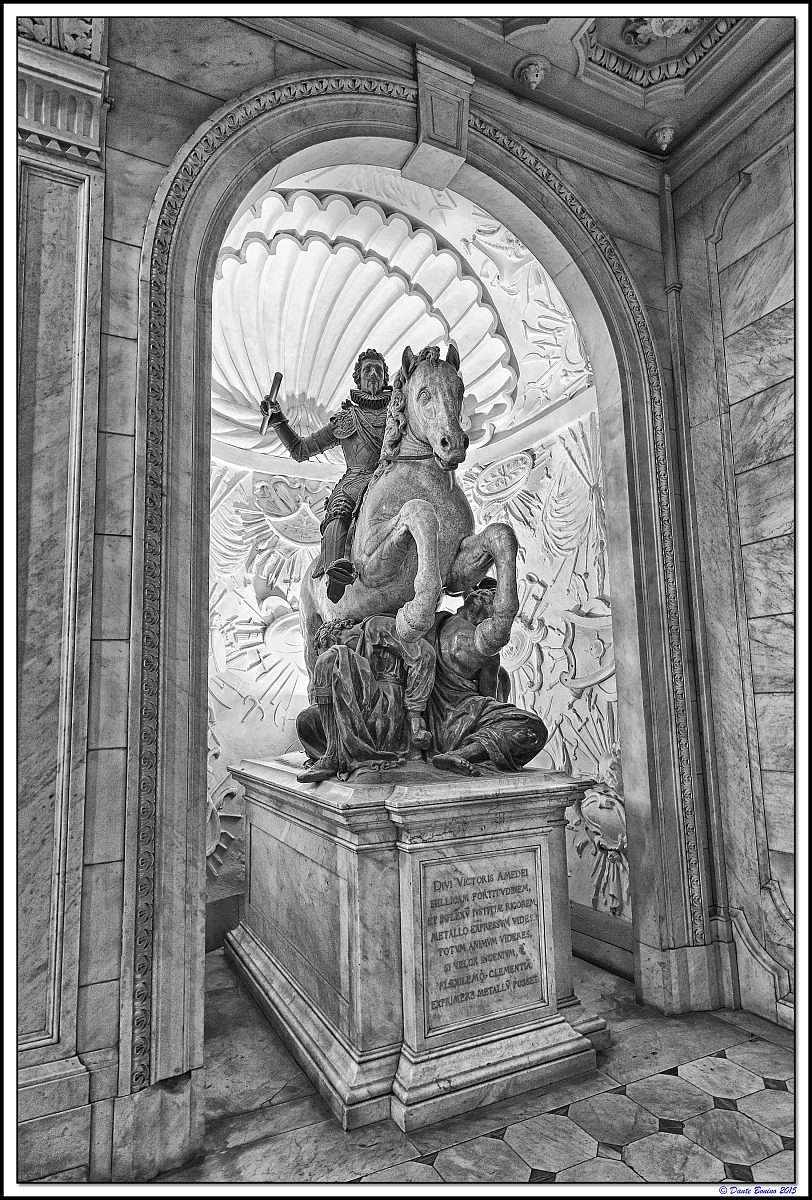

Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy to Vittorio Amedeo I of Savoy

The sculpture parts were completed but remained in storage in different locations in Turin.

His grandson Charles Emmanuel II ordered the construction of an equestrian statue to glorify his father, Vittorio Amedeo I, the son of Charles Emmanuel I. Someone has remembered about the unassembled sculpture, and, after the facial transformation, it was unveiled as the statue of Vittorio Amedeo I. It is now on display in the Royal Palace of Turin.

Ferdinando II de’ Medici of Tuscany to Peter I of Russia

In the estate inventory of Pietro Tacca’s son Ferdinando made in 1687, one of the figurines is listed with a wax model of the head of Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1610-70) attached to it.

His son, Cosimo III de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1642-1723), maintained lively contacts with Tsar Peter the Great of Russia. He had Russian painters and sculptors trained in Venice and Florence. Russian court may have acquired the statuette at the beginning of the 18th century. The head of the Medici Duke was probably replaced for Peter I of Russia‘s head by the Russian court artist Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli (who was born in Florence).

Statuettes With Replaceable Heads, Austria, 17th Century

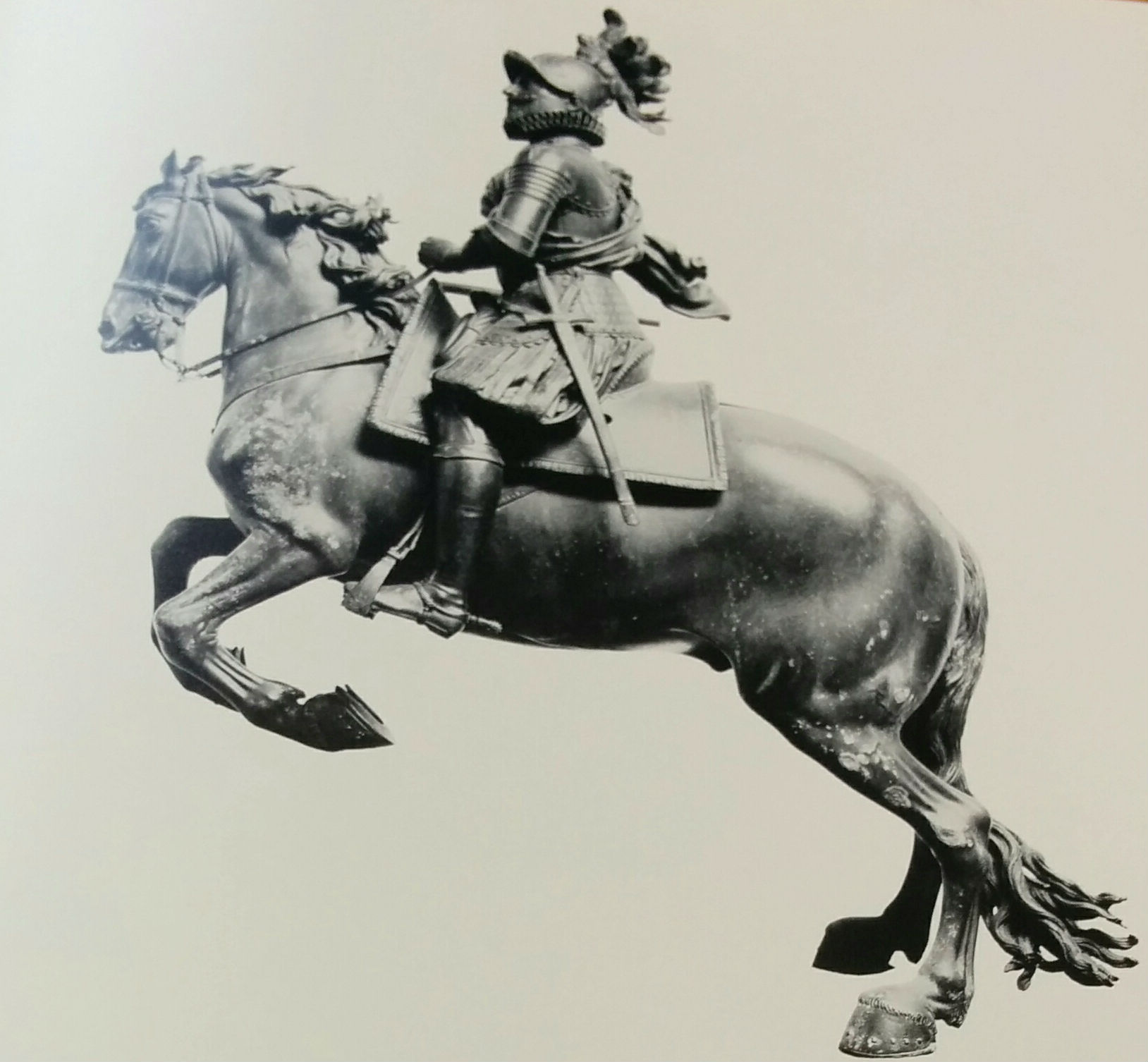

Caspar Gras, an Austrian artist, was well ahead of his time. He created a series of very similar statuettes of Austrian rulers, thus combining his artistic and economic acumen. In addition, he supplied two replacement heads for these statuettes. Four of these statuettes (and both replacement heads) are now on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, one in Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and a few have emerged at auctions.

Zurab Tsereteli, 1992-present

The idea of head replacement does not belong to the past. Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli has created a monument to Columbus that he wanted to offer as a gift to the United States since 1992. After multiple rejections, the monument has ended up in Puerto Rico. As of late 2015, the monument still was not assembled.

Undiscouraged, Tsereteli has produced a very similar Peter the Great Statue that has been planted in Moskva River, which has also caused much controversy.

Further similar monuments have been suggested.

Leave a Reply