3,000 Years Of Horsemen On Rearing Horses: Motivation And Contributions

All art intuitively apprehends coming changes in the collective unconsciousness... Art is a kind of innate drive that seizes a human being and makes him its instrument. The artist is not a person endowed with free will who seeks his own ends, but one who allows art to realize its purpose through him.

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961)

All science is either physics or stamp collecting.

Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937), as told to John Desmond Bernal

The key to a great story is not who, or what, or when, but why.

Elliot Carver, Tomorrow Never Dies (James Bond franchise), 1997

This work contains over 1,500 objects that show horsemen on rearing horses.

However, it is not about the horsemen!

It gives us the following:

- We can see art as a continuous process, a flow, rather than a random sequence of valuable objects. We can see how the trends, like the waves, appear, rise, then fall and eventually disappear. Similarities in styles, techniques and people who appear in these images will inform us about the links between different epochs and cultures;

- The choice of who is represented as a horseman (or a horsewoman) will tell us about who matters, who is on the pedestal, when the art object was created, etc.;

- We can see how artistic styles and techniques, the role of art, as well as science and technology in general, evolve through time.

In a sense, we can try and see the progress of the horsemen as a physical phenomenon, but not the deterministic physics Ernest Rutherford had in mind, more like the light in Richard Feynmann‘s quantum electrodynamics. Indeed, any given light particle photon behaves randomly, and any given art object is random. But, just as the rays of light have a predictable trajectory, defined by the environment and the objects that absorb light or allow it to reflect against, the overall trajectory of art is determined, or, as Carl Jung has suggested, it anticipates the transformations of the society within which it is created.

Contributions

I was trying to allow the objects to do the talking and only add verbal information when it is not straightforward to deduce it from the pictures.

The list of some of the existing research works that make the connections is below.

The Origins of the Formula Of a Horseman on a rearing Horse

In “The Intaglio of Solomon in the Benaki Museum and the Origins of the Iconography of Warrior Saints”, Christopher Walter points out that

Scholars have speculated as to the origin of the formula. Goodenough suggested that it derived from Egypt and that is was taken over from the Thracian good Hero. However, triumphal figures on horseback trampling or spearing a fallen enemy were so common in antique imperial and funerary imagery that it is hardly possible to fix a precise origin for the triumph of Solomon,…

This 4-parts work hopefully places Thracian good Hero, Solomon and many more in the context and gives sense to the chain of transformations of the image of a horseman on a rearing horse.

Adding missing connection elements in the Genealogy of Horsemen on Rearing horses

This Getty museum research article makes a link between Bellerophon and Saint George but omits possible connections with the Middle Eastern images, depictions of royalty etc.

A more complete genealogy of horsemen on rearing horses can be found here.

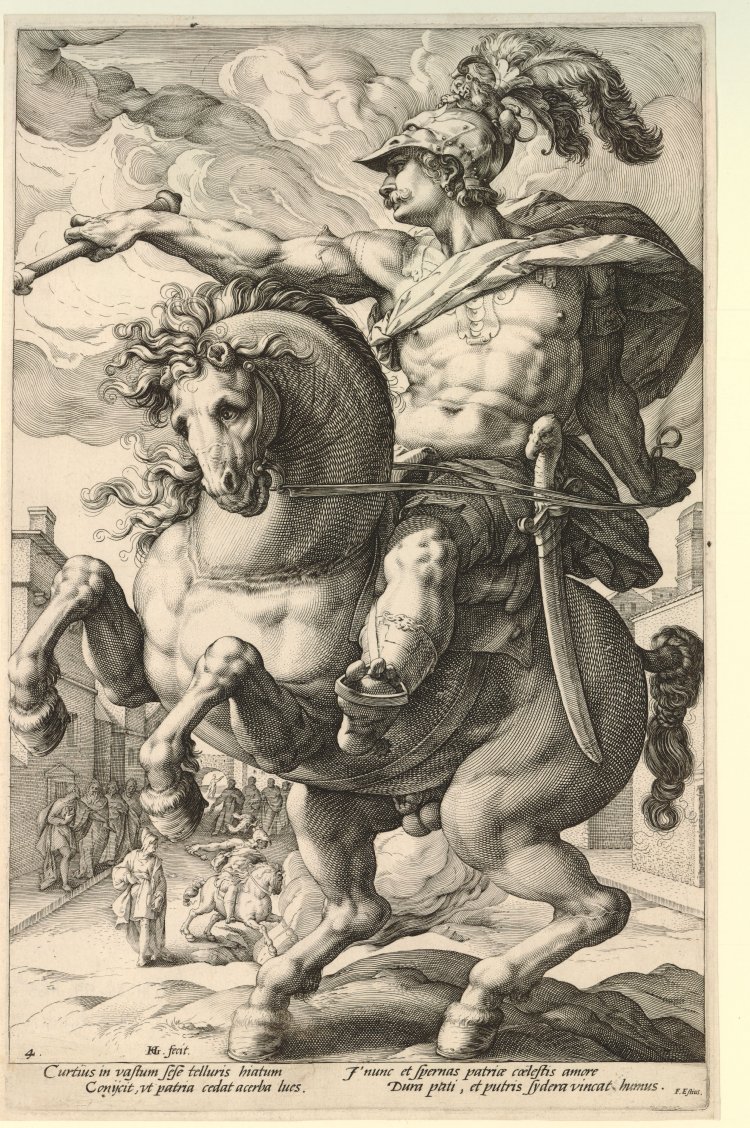

Emperor Charles V at Mühlberg: Finding Missing Precedents And Echoes

We could argue that, while prior portraits of contemporary horsemen with similar iconography are indeed unexistent, many prints and possibly tapestries with comparable iconography were produced at that time north of the Alps, some in the Italian manner. In addition, we can find Italian portraits of Marcus Curtius. Thus, this portrait is indeed exceptional in quality, but very well fits with other equestrian portraits produced at that time in other art forms.

As for the echoes, there is one painting that was definitely an echo of the Titian’s painting: portrait of Reinoud III van Brederode, a member of the privy council and chamberlain to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. The painting is of inferior quality, made just two years after the portrait on an emperor, most probably an attempt of the sitter to link himself to the emperor through art. Then there were two portraits of French kings, Charles IX of France and Henry IV of France, both painted in oils, both of lower quality compared to Titian’s masterpiece, but noticeable regardless.

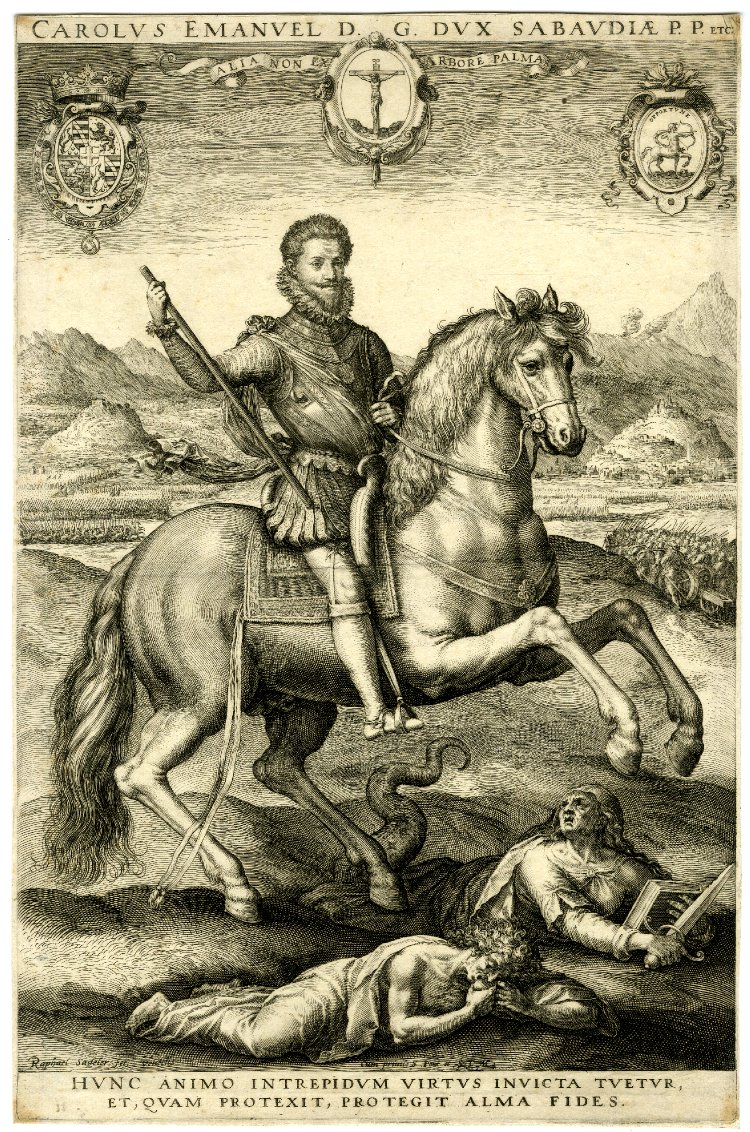

But what really creates continuity is the abundance of printed portraits of royalties on rearing horses, many of which were following very similar iconography, including the angle at which you see the horsemen.

If you look at Rubens’s portraits, the first one shows the horseman and the horse at an unorthodox angle: the chest of the horse is facing the viewer. However, two later portraits comply with the standard set by the prints. This suggests that Rubens’s portraits were not created in the vacuum, but indeed they were influenced by the portraits and prints that were created earlier.

First Large-Scale statues of a horsemen on a rearing horse

The first project of a large-scale statue of a horseman on a rearing horse was not the famous project of a statue of Francesco Sforza designed by Leonardo in 1480s, but a project of a statue for the monument of Niccolò III d'Este designed by Jacopo Bellini in 1440-1470. Unfortunately, his project did not win the competition, and, had it been realised, the statue would, in all likelihood, be unbalanced.

Balancing the large-scale statue of a horseman on a rearing horse is not easy.

Famously, the statue of Philip IV of Spain, designed by Pietro Tacca and completed in 1640, widely assumed to be the first completed large-scale monument of a horseman on a rearing horse, was balanced using the method suggested by Galileo Galilei, and it was using the tail as its third support point. The other widely accepted assumption is that the first large-scale statue of a horseman on a rearing horse with two support points (the tail is up in the air) is the statue of Andrew Jackson, the 7th president of the U.S.A., designed by Clark Mills (sculptor) and completed in 1852.

Both assumptions seem to be incorrect. As early as in 1632, Caspar Gras has designed a statue of Leopold V, Archduke of Austria (1586 – 1632) for the fountain in Innsbruck. The statue was completed but, unfortunately, it could not be installed until 1893, probably because of the death of the duke, thus not taking the place in the history of arts that it deserves.

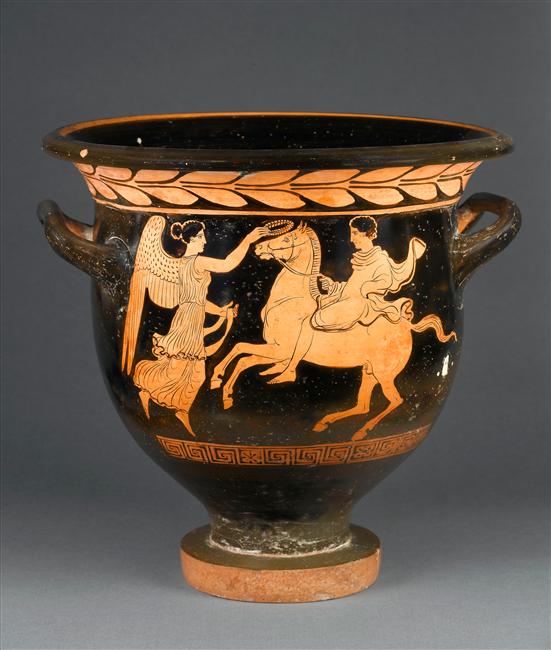

Byzantine Bowl: Origins of the Motif

The description of the bowl with a scene of a triumph of Constantius II states:

The vessel shows a composition typical of Roman coins: the Emperor on horseback is piercing the enemy with a spear.

Yet the iconography of the image is perhaps closer to what we find on Greek vessels. We also find somewhat similar imagery, a royalty on a rearing horse being crowned by a deity, on Sasanian silver plates, although their equivalents of Nike/Victoria are much smaller and are flying rather than standing.

A larger selection of objects showing rulers on rearing horses receiving victory emblems from deities can be found here.

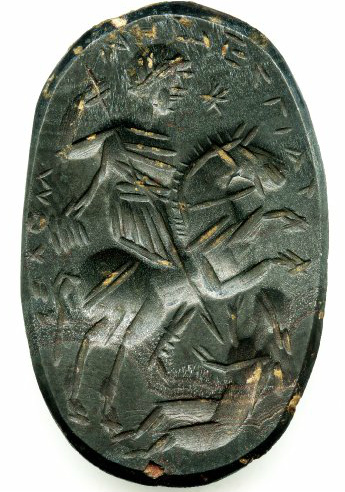

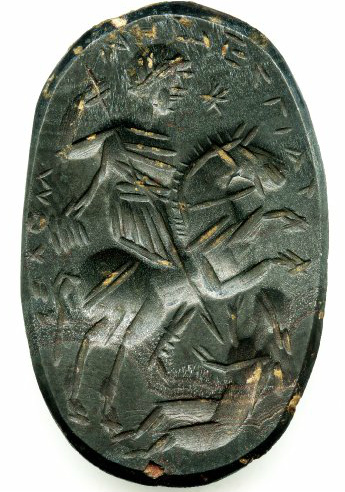

Magical Amulet

Véronique Dasen in her paper Magic and Medicine: the Power of Seals has quoted C. Bonner, “Studies in Magical Amulets. Chiefly Graeco-Egyptian”, saying that

The motif of the rider may derive from Horus stabbing a crocodile personifying evil, or the hunting emperor struck on coins, though Solomon is not in military costume.

The analogy with the hunting emperors struck on coins seems imperfect because they seem to be engaged in game hunting rather than in a fight of good against evil. Egyptian analogy also appears imperfect: indeed, Horus had been depicted spearing Set, who was personifying evil, but, except for one highly idiosyncratic window decoration, Horus was depicted on foot, not on horseback.

It seems that the depictions of Bellerophon spearing Chimera and also some ancient Greek imagery make a much closer analogy.

Leave a Reply